Growth in jobs, pay and output

- Published

The rise and rise of UK employment has taken a jolt, with a fall of 67,000 in March to May and the first rise in unemployment for two years.

The increase of 15,000 seeking work was precisely matched, according to the Office for National Statistics survey, by the fall of 15,000 in the number of Scots seeking work at some point during the spring months. One thousand more Scots were in work.

Watchers of the Scottish figures won't feel this more welcome jolt to be much of a surprise. It's been a bumpy ride in recent months, most of which have seen the Scottish employment picture worsen relative to the UK as a whole.

These most recent figures return Scotland to a better position (just) of 5.5% unemployment, while the UK is at 5.6%. The Scottish employment rate remains higher.

The unusual aspect of the UK-wide jolt is that rising unemployment has been accompanied by a sharp increase in pay. Economists don't usually expect those to go together. But these continue to be abnormal times, as the labour market adjusts towards something like normality, or perhaps a new normal.

Second jobs

The Scottish job statistics show that most jobs growth is in full-time work. The number of people in part-time work is growing more slowly, and fewer of them are telling ONS surveyors that it is because they can't find full-time posts.

The numbers in temporary posts have been falling. It appears that women have been the ones leaving temporary posts and going full-time, while there's also a rise in women taking a second job (more than 60,000 of them in Scotland).

The number of men in temporary roles is on the rise too, but they're much slower to get a second job.

The overall picture emerging from this reflects the strengthened bargaining position of workers, while employers accept they have to sacrifice some of the flexibility of the temporary, contractorised job market if they're to get the people and skills they need.

At 3.2% annual growth rate for June earnings, including bonuses, that's the fastest rate for five years, and with consumer price inflation back at noflation, it means a significant rise in real earnings.

It helps fuel speculation that there could be more inflation coming back into the economy, for which the Bank of England may have to consider an interest rate rise.

The pay figures bear out the view shared by trade unions and the Chancellor of the Exchequer that "Britain deserves a pay rise".

Not the public sector, though. It has been pegged back to no more than 1% for each of the next four years, though Holyrood could choose to vary that, if John Swinney can find the money. You can see tensions stoking up between public and private sector pay.

George Osborne's announcement of a "national living wage" in the Budget last week, which caught the headlines, is now catching the ire of business bosses, in some sectors at least.

The chairman of Wetherspoon's has weighed in with a warning that the higher pay creates "considerable uncertainty" about the future of the pub industry.

It's already suffering from very tough competition from off-licences, notably supermarkets, while drinking habits are changing unfavourably.

His reckoning is that a £1 pint of beer sold in an off-licence carries staff costs of about 10 pence. But a £3 pint sold in a bar carries staff costs of 75 pence. With his trading update, he's reporting squeezed margins.

Construction

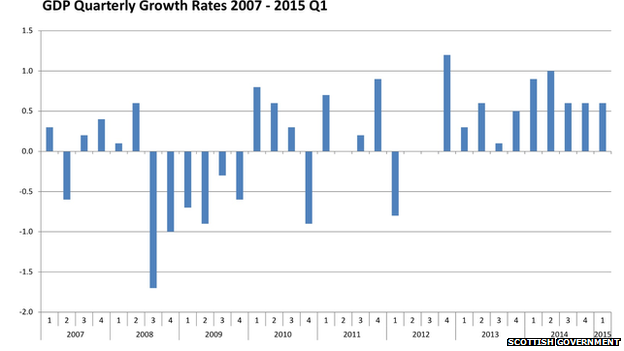

What, then, of Scotland's growth figures? A rise of 0.6% for January to March is reasonably healthy, given other more negative indicators at the start of the year.

It is slightly ahead of the UK thanks, once again, to the figures showing construction in Scotland has been out-growing that of the UK more widely.

Construction output is up 21% compared with the start of 2014, whereas it was up only 4.5% in the UK figures.

That may be partly explained by the big projects currently under way, many of them funded by the Scottish government; the Border railway, the Forth Replacement Crossing, the M8 upgrade in Lanarkshire.

Also helping to grow the economy more than most were hospitality (in a strong year for tourism), transport equipment (such as bus-building in Falkirk) and chemicals and refined petroleum (at Grangemouth).

The sector that's been performing much less well is textiles, with output down 13% in the year to March. The metals and machinery sector has performed poorly too.

Per heid

The Scottish economy grew by 2.8% between the first quarter of 2014 and the first quarter of this year, while the UK economy grew by 2.9%.

But remember that the population is growing at different speeds, largely due to migration, and the output per head is an important measure of whether productivity is on the rise.

That growth rate per head in the year to March was 2.5% for Scotland and 2.2% for the UK. Since 2012, output per capita was up 5% in Scotland, ahead of 4.6% in the UK as a whole.

That suggests something is going relatively right. But it's relative to a poor performance. The whole of the UK needs to do more to get productivity rising, not least to make those wage rises sustainable.

- Published15 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published5 July 2015