The New Highlands at 50

- Published

Five decades ago, the Highlands and Islands were in long-term decline

The Highlands and Islands Development Board was set up with a radical vision to reverse that, and above all, to turn round de-population

Giving out grants and building infrastructure, it had some failures, but the main task has been a stunning success

It is an example of government intervention in the economy and in supporting communities that could carry lessons elsewhere

What has government ever done for us? Or Europe? Or immigrants? All questions that stand a good chance of starting an argument. Except in at least one part of Scotland.

It's 50 years this month since six staff started work for the Highlands and Islands Development Board.

Its first year budget ran to £106,000, in addition to the grants it disbursed. It was the first time businesses had been supported that way.

And while it continued to have a relatively small part of the government's spend in the area, its foundation marked a significant turning point.

This was a small revolution in the way government did growth. It was the start of a success story.

It means the region is now rated among the very best places to stay in Britain. It's no longer the case, as it was then, that the Highlander is "the man on Scotland's conscience". And the way it was done may even have lessons for us now.

State and society

The board had been part of the programme of the Labour government elected the previous year. The new administration had a National Plan, which included a lot of state involvement in directing the economy.

In the HIDB, there was an unusual social remit added, to develop communities as well as industries.

The vision for Scotland went much further with the Plan for Expansion, published 50 years ago in January, setting out how £2bn would be spent over five years.

Industrial and regional policy were closely linked for Harold Wilson's ministers. Permission to develop industries in and around London was withheld, and grants poured into industrial development further north.

White heat

The prime minister had talked of "the white heat of new technology". It felt like a new era. New industries could be encouraged, to replace those declining, as coal and shipbuilding then were.

Aluminium, car-making and electronics were among those chosen for Scotland. New Towns were growing fast, from Glenrothes to Irvine. The Forth Road Bridge had just been opened, and the first motorways were being constructed.

This was a time of rapid expansion of the universities. Scotland gained four new ones - three of them by upgrading technical institutes to become Strathclyde, Heriot-Watt and Dundee universities.

Stirling was chosen over Dumfries and Inverness to be the site of a modern campus for an entirely new university.

Exiles

One of the main reasons Inverness was not chosen was the A9. Road links from the Lowlands to the Highlands were notoriously poor.

But they were good enough to see an exodus of people and potential in the opposite direction. The Highlands were in a parlous state.

There were many challenges, most of them connected with de-population. The first annual report of the HIDB explains "Operation Counterdrift", looking for Highlander exiles who might be persuaded to return.

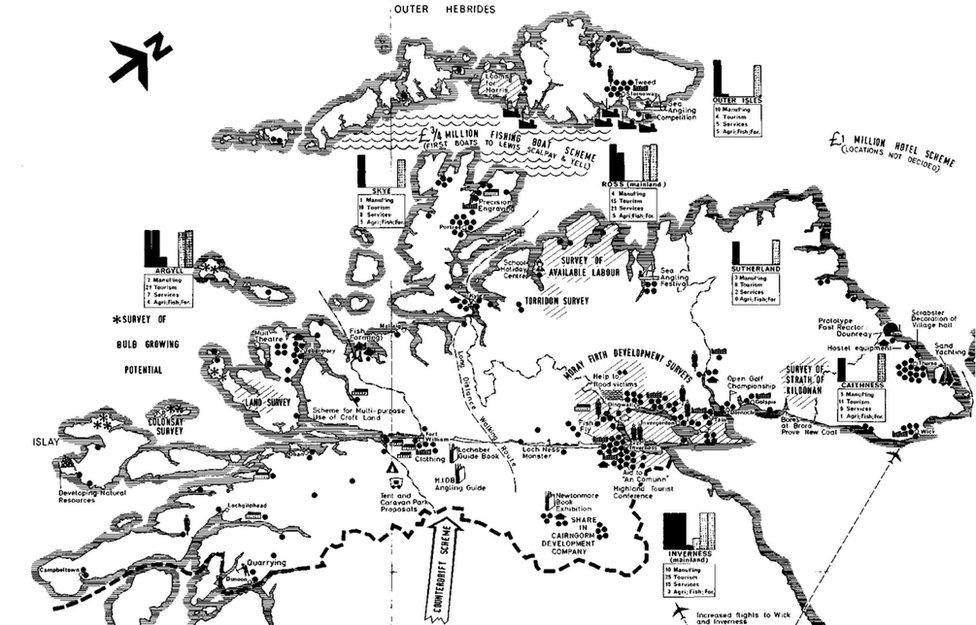

Map from the HIDB 1966 Annual Report

The inspirational chairman, Professor Robert Grieve, makes clear in the report that the board's work was of international significance. His report reflects on outsiders' misunderstandings of the Highlands, and a widespread failure to grasp the potential of tourism.

The prospect of manufacturing was seen as more "honourable" than hospitality, said the report, while some believed tourists would undermine the Highland way of life.

The first year saw £10,000 spent on tourism publicity, and a campsite planned at Glencoe. There was urgent work to get Cairngorm ski facilities improved, and a guide to angling was being prepared.

More ambitious plans were being drawn up to build and lease five hotels. Locations had not been decided. These were intended to have around 100 rooms each, at a total cost of £1m.

The first was built in Craignure on the Isle of Mull. Ten years later, the results included the eccentric Isle of Barra Hotel, which has not been seen as a notable success story. Nor were that island's factories for spectacle frames and fishmeal, or the plans for Uist crofters to harvest bulbs.

Gaelic

Scottish fish farming had begun in 1965. Two HIDB staffers went to Denmark to learn more about it.

There was early support for west coast sea fisheries, but no mention in the first HIDB annual report of the Gaelic language. It would later become an enthusiastic supporter.

The HIDB identified the Inner Moray Firth - from the Moray coast, through Inverness and Dingwall, up to the Black Isle and Easter Ross and into eastern Sutherland - as the region that invited most economic development.

It commissioned the "Moray Firth Industrial Credibility Study", including an appendix about "Possible Energy from the North Sea", and it sunk bore holes near Brora in search of coal seams.

But it also acknowledged the competing claims of the north-west, with more severe de-population problems in the crofting communities.

Those problems have not disappeared, as you can sense on the more remote islands, such as the Isle of Harris. But "Operation Counterdrift" has worked. The Highlander has gained a proud identity, and shed a grievance.

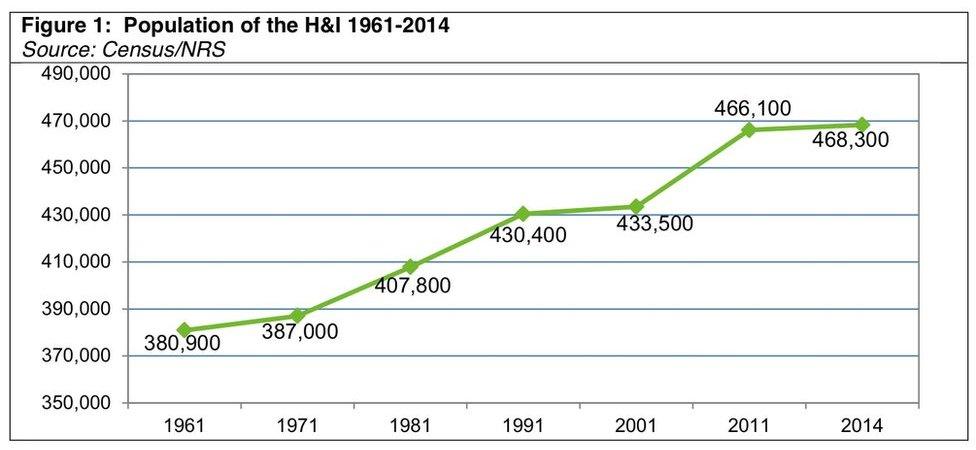

In 1966, the Highlands and Islands had a population of 381,000. By 2011, it had reached 468,000. Last decade, it grew 7.5%, to Scotland's 4.6%.

The number of people living in Inverness was 45,000 five decades ago, and has grown 51%, while it has become a city and embraced a large travel-to-work area.

The population is tilted towards the old, and on course to become more so. Among those who are "economically inactive", 59% are retired - whereas that's true of 48% across Scotland.

A significant number have moved into the area. Some 15% described themselves in the 2011 census as "white British", to 81% "white Scottish".

More than 5% had been born overseas, with the impact of Polish and other European migrants more evident around Inverness than most other parts of Scotland.

University

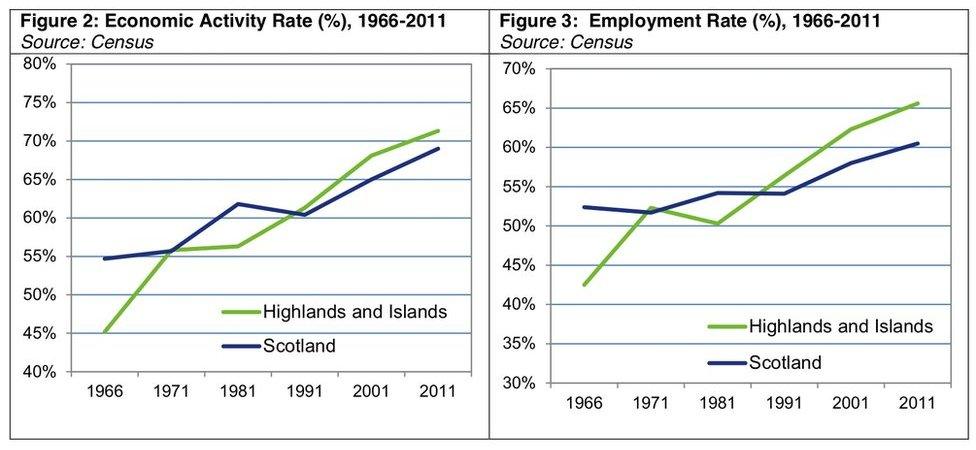

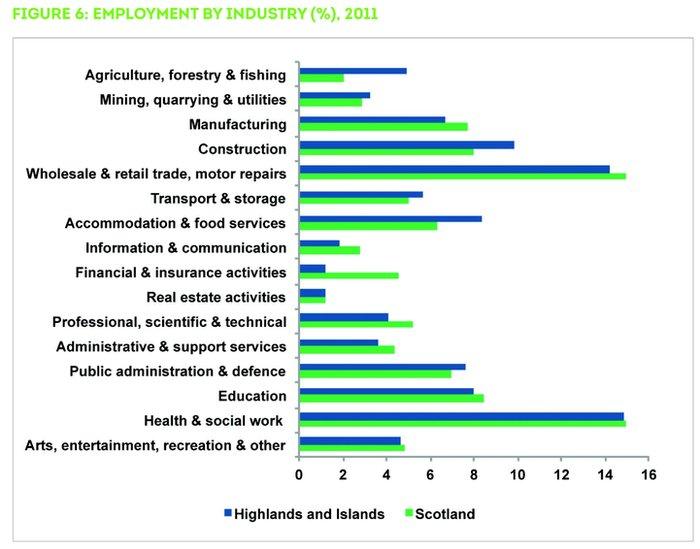

According to figures compiled by Highlands and Islands Enterprise - the successor to the HIDB since 1991 - the area's business base is heavily weighted to small firms, as well as part-time and self-employed workers.

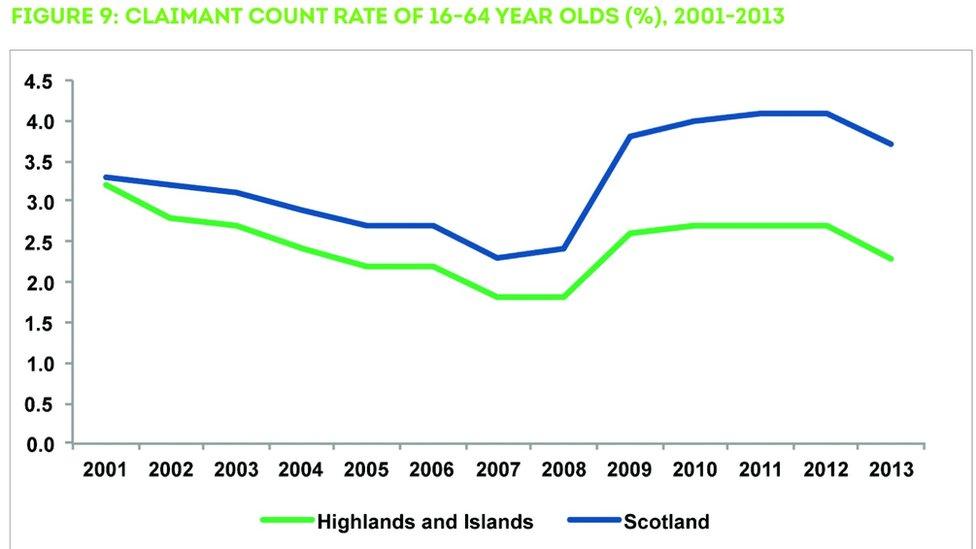

The unemployed claimant count, at 1.1%, is around half Scotland's rate. The area is stronger than Scotland as a whole in skilled trades, and less so in graduate employment.

School leavers are significantly more likely to go into jobs than in the rest of Scotland, and less likely to go to higher or further education. But they are still drawn away to education opportunities to the south.

Immigration

Fifty years ago, Inverness had already lost to Stirling in the university race, but the HIDB identified that a Highland university remained a longer-term aim - but one that took more than 40 years to realise.

Likewise, land ownership was identified in the first years as an issue to be addressed, but it took nearly 30 years before community ownership would begin to gain some momentum. It is being revisited, with new land reform legislation proposed.

Can lessons be learned from all this? One is that measures can be taken to turn around out-migration, focussed on young people and economic opportunity.

In-migration - of Lowlanders, English people and Poles - can sometimes be resented and controversial, particularly where housing is in short supply. But the inflow of fresh thinking and energy can be a significant part of turning the economy and communities around.

A further lesson is that membership of the European Union is widely seen in the Highlands and Islands as having been of great benefit.

Objective 1 funding, granted in Brussels 21 years ago, was one of the programmes which brought big tangible results: new causeways, bridges, port facilities, airport improvements, skills training, and recognition of the cultural value of Gaelic.

Spinal road

Above all, though often discredited, some government intervention of the 1960s and 1970s has delivered a lasting, positive effect.

Yes, as at the Linwood car plant, the Highlands suffered from industrial white elephants - Invergordon in Easter Ross had its aluminium smelter, and Corpach in Lochaber had a pulp mill, while the Dounreay nuclear plant would gain a fast breeder reactor prototype, but is now being decommissioned.

However, the intervention produced results elsewhere and on a smaller, wider scale, building infrastructure and on spec industrial units. This helped turn around population decline. It helped create a diverse economy, and much improved transport.

Clearly, the oil industry helped. And the creation of strategic regional and island councils in 1975 had a big impact.

But at HIDB, it was done by marrying economic with social development. Whereas the enterprise agencies now focus on businesses with high-growth potential, the past 50 years have been more about building the economy where businesses could thrive.

It's hard to imagine how much of this could have happened without the Scottish Office re-building the A9 in the 1970s and 1980s, with three bridges spanning the firths north of Inverness.

Yet its success has led to another wave of development being required. The spinal road through the central Highland mountains is now struggling with traffic demand and is the next big project for Holyrood investment.

However, as my colleague Craig Anderson observed in marking the anniversary on Reporting Scotland, the real measure of success over the past 50 years has been the counterdrift of confidence.

That's hard to measure, but in the Highlands, it's easy to sense.

- Published2 November 2015

- Published4 November 2015

- Published5 November 2015