Scotland and England: growing closer, living apart

- Published

The more Scotland has diverged politically from the rest of Britain, the more it has become economically similar.

It's one of those paradoxes of the 21st century, which was underlined this week by the Resolution Foundation.

The think tank - based in London, with a focus on jobs and income for low and middle-earners - had a right good go at the Scottish economy.

Its most interesting conclusion was that Scottish median income has passed that of the rest of the UK. I wrote last weekend about why that might be, and whether it's still true (to save you time: probably not).

The report showed that household income, since 2007, has increased slightly faster than in London. Only the East Midlands has seen faster growth.

Jobs gap

But the general thrust of the analysis is that Scotland has closed quite a few gaps, not just on pay, but Gross Domestic Product, or total income per head.

It has closed the "jobs gap" - the dip in the employment rate below the pre-recession peak - though the think tank pointed out that it still has a way to go to catch up with England on unemployment and job creation, and that self-employment is much lower than in England.

On a measure of under-employment, at which Scotland was in a better position in 2008, the sharp rise and slower decline has left Scotland close to the UK average.

The proportion of people aged over 50 and still working has risen more steeply in Scotland, nearly matching the UK rate.

The churn of workers voluntarily leaving jobs to get employment elsewhere, has tracked that of England.

So Scotland is no longer an outlier. It is no longer England's poor relation. In some ways, it is more typical of the UK than any region of England - and most of all, London.

Home countries

But in one area, there's a huge difference - housing.

We've heard quite a lot about housing in the past week.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) issued its measure of prices in the year to November. It found London and south-east England up by 9.8%, and Scotland up by 0.4%. It was far behind every region of England except the north-east.

The UK average, according to the ONS, was a rise of 7.7%, to reach an average price of £288,000.

The official register for England and Wales includes cash purchases of homes, and has a lower figure - house prices up by 6.4%, and a much average price.

The nearest comparison, from Registers of Scotland, covers the year to last September. Reflecting on actual transactions rather than surveys, it found prices falling 0.5%, and the average price at below £170,000.

Prices rising

Survey evidence looking ahead suggests the housing cost gap will keep growing this year, though things might slow up a bit.

BBC news online found estimates of the increase in UK prices during 2016 of between 2% and 6%.

RICS, the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, reported this week that its members in Scotland reckon prices will rise this year, but they're far from being unanimous on that.

Comparing those expecting a rise with those foreseeing a fall, there was a 24% majority for higher prices. However, that does not tell us how much higher the surveyors expect them to be.

A more specific question put to RICS members at the UK level found an expectation of London prices rising at 5% per year in the next five years, and 4.5% across the whole UK.

Higher obstacle

That may look good if you're a home owner. But it brings the concern that those selling up and moving out of high-cost regions are able to inflate prices in lower-cost ones.

It's obviously much less appealing if you want to get on the property ladder. That has been made more difficult in recent years by tougher tests of mortgage applicants than before the financial crash.

Uncertainty about the market, slow wage inflation, higher deposits on mortgages, a fall in the number of new homes being built, along with graduate debt and rising private rents making it harder to save: they have all combined to build a significantly higher obstacle to home ownership.

That helps explain why the proportion of people living in their own homes has fallen. The Resolution Foundation report says it is down in Scotland from 47% to 38% since the start of last decade.

The proportion in the private rented sector has more than doubled, from 10% to 22%.

That is linked to the most significant point made in the Resolution report - about the link between home prices and earnings.

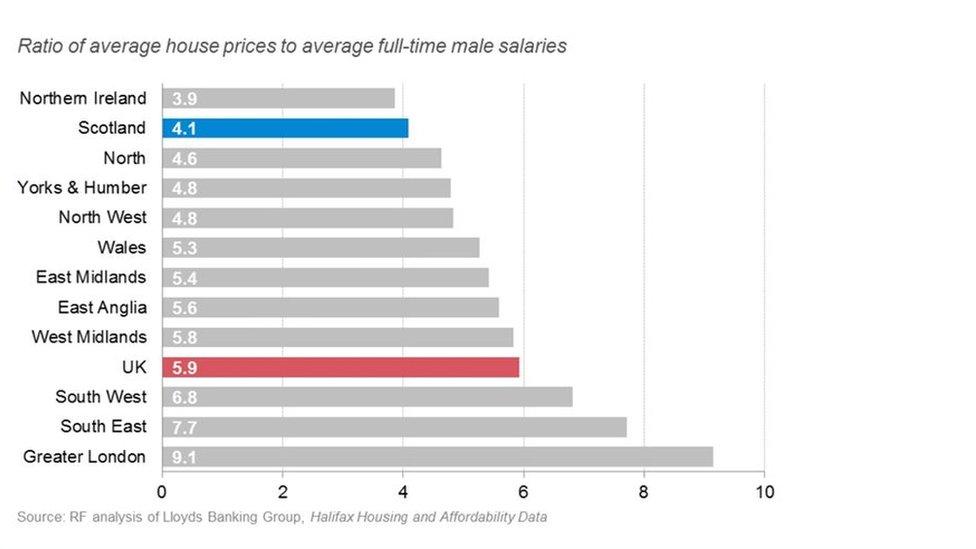

The report has compared the average house price with the average male earnings around the UK. It finds that average house costs 5.9 times more than earnings.

In London, it is 9.1 times higher. In Scotland, it is 4.1 times.

Income share

That is relatively good news for Scots. The share of income required to afford a home is much less, leaving more money for other things......with even hard-pressed Londoners more likely to put at least something aside.

In London two years ago, every local authority area had the average home-owner with a mortgage spending more than a third of net income on housing. In Scotland, none did.

In the private rented sector, all of London's local authority areas had average housing costs above a third of income. For south-east and the east of England, more than a quarter did. In Scotland, that was the case in only one local authority area (or 3%).

And while prices have been rising fast, and may continue to do so at that RICS estimate of 5% per year, no-one expects average wages to rise as fast. That ratio is set to increase.

What crisis?

It's no surprise, then, that Londoners are most concerned about what happens when interest rates on mortgages go up, as they must eventually.

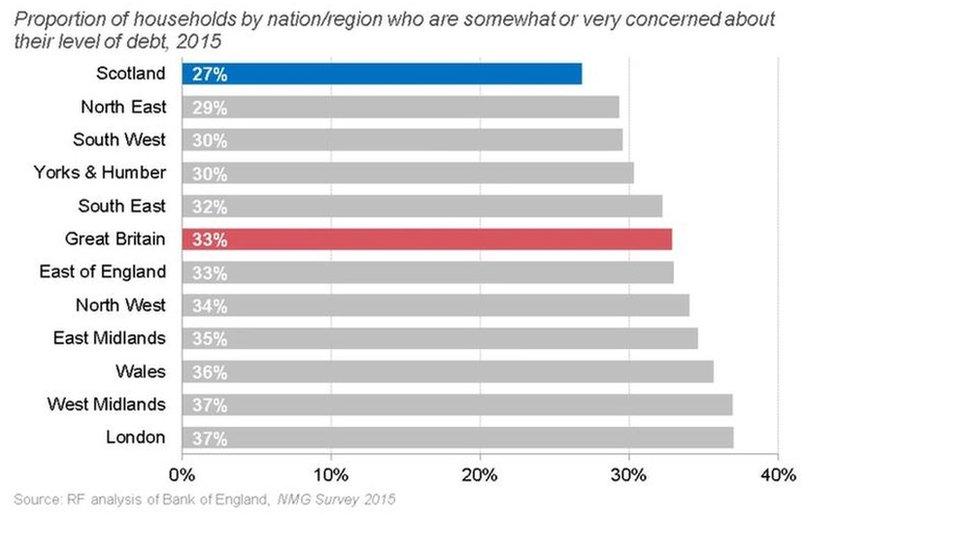

According to a Bank of England survey last year, a third of UK home-owners with mortgages are concerned about their household finances when that happens.

In London and the West Midlands, it was 37%. Scotland had the lowest level of concern, at 27%.

That puts the pre-Holyrood election debate about Scotland's housing "crisis" into some context.

Demographics point to more demand for homes, and pressure for house-building if prices are not to go up fast. But for now, from the household finance point of view, it is much less of a concern than for the southern neighbours.

Viewed from London, where monetary policy is set, the pressure from house prices is intense. The push for more house-building is a higher priority. And the risk of another price bubble is rising.