Whatever happened to Silicon Glen?

- Published

It's not that long since Scottish factories made three out of every 10 personal computers built in Europe. Nearly two-thirds of Europe's cash machines were from Dundee.

Not any longer. Silicon Glen - the name given to the mainly central belt electronics manufacturing phenomenon - continues to decline.

The announcement from Texas Instruments that it is pulling out from Greenock, continues the trend.

The tech giant, with 30,000 employees around the world, is to move Greenock's chip fabrication to German, Japanese and American plants - not, you'll note, low wage economies.

There go 365 jobs, though not before the end of next year.

Not glamorous

We've seen plenty such announcements before, few of them easing the pain with such a delay.

National Semi-conductor was taken over by the Texans five years ago, having been one of the more significant features of Silicon Glen's topography, since first opening up in Inverclyde in 1970.

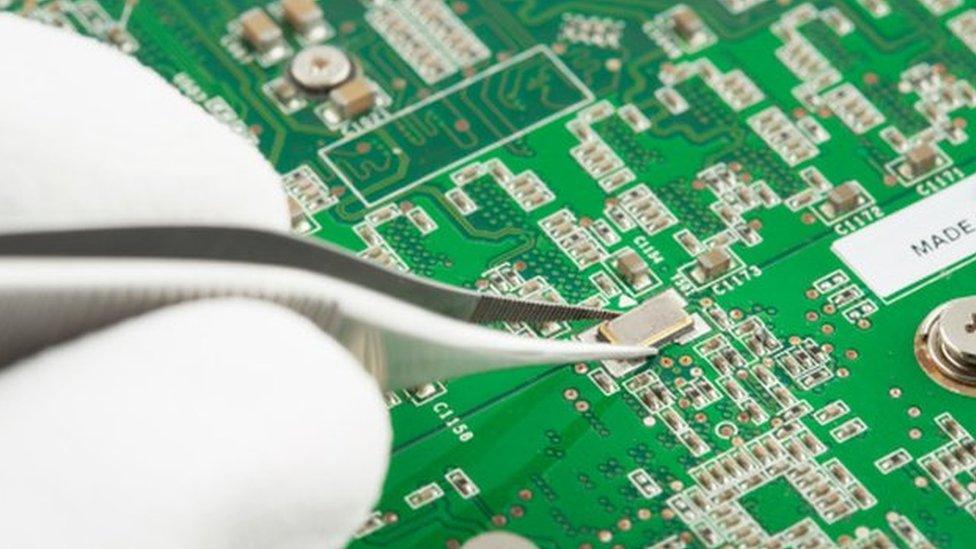

This was not glamorous work. That Greenock plant was criticised for its working conditions. But the Silicon Glen phenomenon was important to replacing the jobs from old industries, which were dying as electronics arrived.

The new manufacturers, often headquartered in the US, Japan and South Korea, helped Scotland's new towns establish themselves as economic hubs. They brought new, more efficient work practices, which benefited the wider economy. And they were a means for bringing many more women into the workforce.

The priority then was for the Scottish Development Agency (predecessor of Scottish Enterprise) was to attract inward investment with large job numbers. The quality of the jobs didn't matter so much.

Some firms brought higher-skilled jobs, with support services, research and development, so that when the manufacturing left, there was a valuable legacy - at IBM in Greenock, for instance, and NCR in Dundee.

But most of these jobs had shallow roots in Scotland. They were rapidly culled after the dotcom bust at the turn of the century, while the opening up of quality manufacturing in Central Europe and China enticed the multi-nationals to move production to cheaper, low-wage locations.

Export dominance

Within minutes of Texas Instruments confirming its plans to shut up shop in Greenock, the Scottish government was publishing the latest export statistics, covering 2014.

It illustrated what has happened to the sector. In 2002, the value of computer equipment exports was £5.6bn, when electronics accounted for 28% of Scotland's exports.

By 2014, that was down to £1.1bn, and 4% of exports.

Other Scottish government statistics show the fall in value of manufactured electronic equipment, at 2013 prices, from more than £16bn in 2000 to less than £2bn only 13 years later.

For all the volatility of the oil industry, there is no sector that witnessed such a sharp decline as electronics.

In 1999, it represented 32% of Scottish manufacturing value. Fourteen years later, that was 8%.

The share of employment was less significant, both in reaching 16% of manufacturing jobs in 1999, and in the less steep decline to 9% by three years ago. That's a reminder that its importance can be overstated.

Screwdriver jobs

It was clear, even before the bust, that Scotland's economic developers had to shift from attracting screwdriver/assembly jobs, and "move up the value chain".

Grand plans were set out for Project Alba, with thousands of graduate level jobs in Livingston, anchored in an investment by a Californian firm called Cadence. It didn't come to much.

But it was a pointer to the way in which the electronics industry would go in Scotland. Instead of making stuff, the move has been to deeper skills in designing and deploying electronics.

Silicon Glen's workforce may have plummeted from its peak at nearly 50,000 jobs, but electronics and information technology have infiltrated so many other sectors that it is reckoned more than 80,000 people can now be considered digital.

They work across oil and gas, financial services and innovative healthcare. For recruiters, IT skills are consistently the ones in most demand. Those who have them can pick also from the consumer and internet companies which want to be in Scotland for its skills.

These include global brands such as Amazon, which has just announced an expansion of its IT development team in Edinburgh.

Rockstar North, the company behind Grand Theft Auto computer game, now occupies the prestigious office built for the now-much-diminished Scotsman newspaper.

Skyscanner, the travel search engine, also wants these skills, building Scotland's biggest online consumer brand from close to Edinburgh University's dynamic presence.

There are reckoned to be more than 1,000 tech companies in Scotland now, many smallish and digital a common factor.

Brain-powered

This week, work began to clear the site of the Tullis Russell paper mill in Glenrothes - not long closed with the loss of nearly 500 employee-owner jobs. The plan is to replace it by a data centre, powered by renewable biomass energy - symbolic of the shift from paper to gigabytes.

Exports from such companies are not easy to count by standing with a clipboard on the quayside at Grangemouth. They are digital, and flow instantly down cables.

Because the digital economy is ubiquitous, there is little need to have a name for this. Silicon Glen has all but had its day as the badge for an important part of the transition from the old and manufacturing economy to a computerised and service-based one.

The departure of what's left is of course painful for those affected. But the loss is rarely mourned, as the Scottish economy adjusts to a present and future which is digital, brain-powered and forever in flux.