The King of Good Times, de-throned

- Published

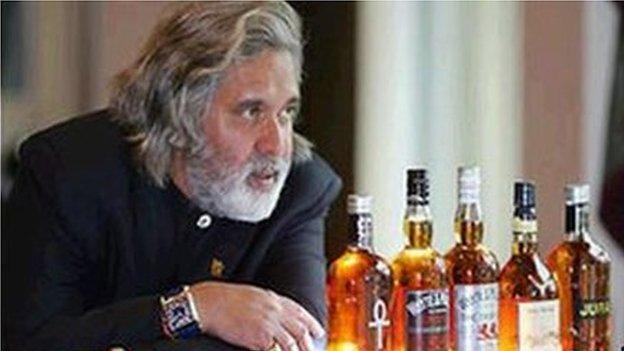

To the genteel, oak-casked, bourbon-tinted, copper-stilled world of Scotch whisky, Vijay Mallya arrived with an extravagant splash of spice, bling and a vast wad of rupees.

The industry had never seen his like before. It's unlikely that it will again.

That's because the reign of India's self-styled "King of Good Times" has come to an end.

Having o'er-reached himself, he has been forced to abdicate - perhaps into exile. And the deed was done by brute corporate power, wielded by the biggest name in Scotch and in world spirits.

Diageo has gained control of India's biggest distiller, United Spirits Limited (USL), and thereby dominates the world's biggest whisky market.

It has had a controlling stake of shares, building up to a majority since 2013, and now at 55%.

But things in Indian business are rarely straight-forward. Mr Mallya, who had been forced to sell, clung on to the chairman's seat at USL, even when the majority shareholder was publicly trying to shame and oust him.

The London-based company has got its way now. A business empire has been crushed into the dust of the Deccan plain, with a jaw-dropping deal announced to the stock market on Thursday evening.

Personal brand

To recap, Vijay Mallya has, for more than 30 years, occupied a business space somewhere between Donald Trump and Richard Branson. He's less pugnacious than Trump, but he has invested in a one-man brand to project the billionaire lifestyle.

He's clearly been a lot less successful than Branson, but he had a similar approach to building up an empire of lifestyle businesses, linked by that personal brand.

Mallya cashed in on the growth in leisure time and disposable income in his home country's burgeoning middle class.

So there was Kingfisher beer, hugely dominant in India, and with an international reach. It is produced by United Breweries, the biggest such company in India, and inherited from Mr Mallya's father.

Vijay set up Kingfisher airline in 2005, linking the "good times" brand from his beer to what had become, to India's middle class, the newly-affordable glamour of flying.

The airline/beer branding was all over his Force India Formula 1 team, formed around the time that F1 extended its global reach into the country.

He was a key figure behind the growth of the Indian Premier League (IPL) in cricket, a rupee-rolling sports business phenomenon that has to be experienced to be believed.

Eight years ago, Mr Mallya bought the IPL's Bangalore franchise for more than £70m. He named it after one of his whisky brands, Royal Challenger.

Earlier this month, with Mallya calling the shots, it paid the highest price in the auction for IPL players - more than £1.2m for Australian all-rounder Shane Watson.

Mallya struck a sponsorship deal with the Mohun Bagan football team in Kolkata - the current top flight champions and oldest professional club in the country.

This wasn't merely about the shirt logo or the stadium, but the West Bengali team itself. To promote India's number one whisky brand, it became McDowell's Mohun Bagan.

There was lots more besides for this one-man conglomerate: pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, fertilisers, real estate, and election to India's parliament as an independent member.

Trademark flamboyance

So when Mr Mallya touched down in Glasgow in 2007 to take over the venerable Whyte & Mackay business for a staggering £595m (three times the price paid for it six years earlier), he brought more showbiz fizz than the Scotch industry was used to.

I met and interviewed him five years ago, when he flew from New Zealand to Glasgow in his personalised Kingfisher Boeing 737.

He brought a few bottles of Ernest Shackleton's whisky, which had been frozen and forgotten for a century under the Antarctic explorer's hut.

With trademark flamboyance, Mallya's pilgrimage to the home of whisky was to get Whyte & Mackay's top Scotch blender to replicate Shackleton's dram. You can buy it now, Shackleton's Mackinlay, for at least £200 per bottle.

The chairman told me, during that Glasgow stopover, that he expected USL soon to surpass Diageo's spirits sales - not by value, admittedly, but by volume.

It's all gone south, however - financially at least. Mallya's undoing was mainly Kingfisher airline, which flew an expensive fleet of aircraft too close to the sun gods.

It became hopelessly overstretched, yet somehow continued to fly for 15 months when it wasn't paying its pilots or cabin crew.

It was grounded in late 2012, and a consortium of 17 banks, several state-owned, is pursuing Mr Mallya for billions in loans, with some assistance from Indian law enforcement.

Assets had to be offloaded. Last year, Heineken surpassed Mallya's controlling stake in United Breweries. And with USL forced into the market, Diageo didn't have to be asked twice if it was interested.

Along with the Scotch whisky industry as a whole, the dominant player has long been well aware that India is a richly flavoured cask just waiting to be cracked open. If only it would lower that 150% import tariff.

But in the meantime, there's good business in "Indian-Made Foreign Liquor" with strikingly Scottish-sounding names - not just McDowell's, but also Bagpiper.

Squinting anew at the USL books, auditors were puzzled by the unusual transfer of funds across companies controlled by Mr Mallya, at a time when his airline was badly in need of cash. They insisted on qualifying the accounts.

The London-based spirits giant, which had just taken control, went public with its concerns about possible and quite serious illegality. It tried to force Mr Mallya to resign. But he refused.

With its July-December figures, issued a month ago, a lot of small print made it clear that a formidable case was being built against Mr Mallya.

Some £93m had been booked by USL to deal with possible losses through money being transferred out of its funds.

That is while it was battling with creditors of United Breweries over entitlement to a similarly-sized tranche of Mr Mallya's former assets.

By this week, a deal had been done, and legal threats put aside. It may have been an offer the USL chairman couldn't refuse. But he must have had some good cards in his negotiating hand, because Diageo has agreed to pay out a lot.

Thirteen homes

Over five years, the company will hand Vijay Mallya $75m. That's £53m. He gets $40m now, and the rest in five instalments.

For that, he gives up on the previous agreement not to depose him as chairman. He leaves the board. And he's signed up to a no-compete, no-interference agreement everywhere except, interestingly, the United Kingdom.

He gets first refusal on no fewer than 13 Mallya homes which somehow found their way on to the USL books. Some, in Mumbai and Goa, will be at a 10% discount.

For two years, Diageo will not object to his son, Sidhartha, sitting on the board of the USL affiliate that controls the Royal Challengers Bangalore franchise.

Mallya Senior loses financial control of Force India motor-racing, which can no longer expect sponsorship deals with Diageo. That's apart from the Smirnoff brand, for which Diageo sees a value in continuing to spend $11m annually, for five years.

Gone are the sponsorship contracts with Kolkota football and with a horse-racing enterprise.

Diageo is to book the £53m cost of this, in its next accounts, under "exceptional items" - which may be something of an accountant's understatement.

Chief Mentor

Vijay Mallya now has a new title: "Founder Emeritus" of United Spirits. If that sounds good, the trappings of corporate power don't come with it. Rights, responsibilities, entitlements and benefits are expressly ruled out.

So long as his son is on the board, he will have the title of "Chief Mentor" to his cricket team, which is nice, but also looks a bit meaningless. The deal states that board directors "may, if they choose, consult him".

And his take on all this? Well, he turned 60 in December. It's that time in life when he would like to spend more time in England, with his children.

That conjures up a picture of a grand-dad tending to his vegetable patch somewhere leafy in the Cotswolds.

But my hunch is that we haven't yet heard the last of Vijay Mallya.

- Published26 September 2014

- Published9 November 2012