Budget 2016: the productivity and prosperity puzzle

- Published

This was a Budget with a message about the next generation, and a massage of difficult underlying figures.

It wasn't so much "here's a rabbit from the hat" but more: "look over there - a squirrel!"

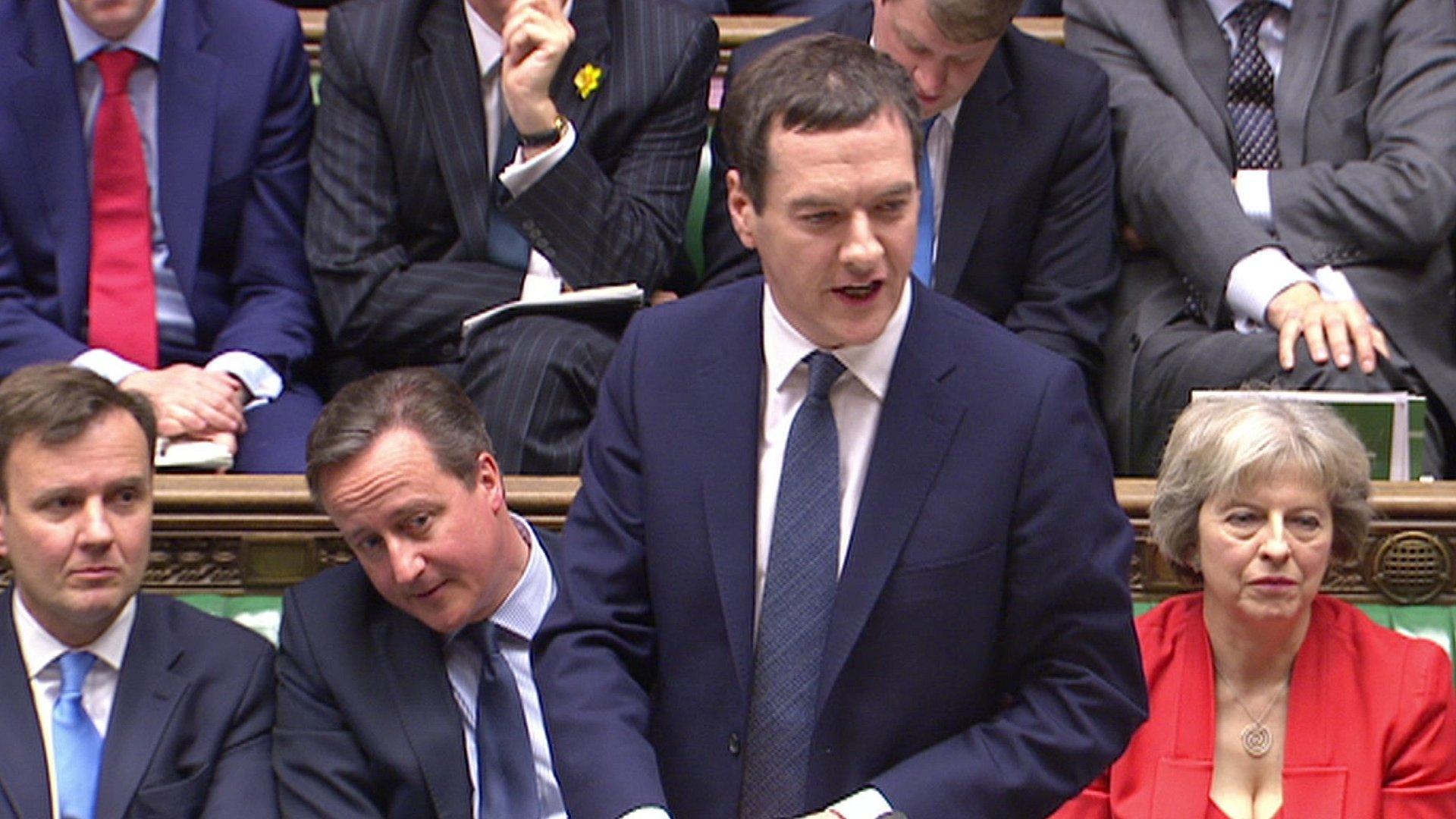

So, with some nasty new forecasts, and without big changes in the near-term tax and spending totals, George Osborne opted to look busy - taking from bigger business and particularly the soft drink firms that put sugar into their fizz, while giving to smaller business, savers and higher rate income tax payers.

He got busy at a very local level, even finding £5m from banker fines to build a leisure centre in Helensburgh. He halved tolls on the Severn Bridge and he's upgrading trunk roads across northern England (which ought to be very welcome to Scottish hauliers).

Meanwhile, as the Chancellor was flunking some of his own fiscal tests, this Budget flunked a test that others had set him - to simplify the UK's horribly complex taxation system.

2020 vision

By the time we find out if the claims of getting to a fiscal surplus, using 2020 vision, we'll surely have long forgotten the Budget of 16 March 2016.

While Mr Osborne sounds confident about getting to a £10bn surplus, the forecasts on which he is basing that have widely divergent possible outcomes. He is going with the central one.

But if you look at the forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility, it has a 'fan diagram' showing the wide range of possible growth outcomes. The variation is not only for 2020, but for 2016 - ranging between growth of a sizzling 3.8% and contraction of a dismal 0.2%.

Knocked back

So as forecasts are near certain to be wrong, how instead might this Budget be remembered? Perhaps for something that George Osborne only briefly mentioned - productivity.

It's turned out disappointingly again. And that's knocked back the growth estimates for the economy, as well as for pay, for tax revenue, and for company profits over the rest of the decade.

Britain's not alone in that. But keeping company with the USA on such numbers is not that reassuring.

While George Osborne didn't say much about productivity, the Office for Budget Responsibility did. It was OBR numbers that forced the Chancellor into that fancy financial footwork.

With its forecast last November, the OBR had taken healthy signs of productivity growth from the middle two quarters of last year, and projected them forward.

However, the fourth quarter pushed productivity backwards by 1.2%, eliminating the progress made in the previous six months. Having assumed 1.4% growth over three quarters, it ended up with nothing.

Pay growth falls

Duly chastened, the OBR turned more pessimistic this month, and reckons productivity will continue to drag.

Back in 2010, when it was set up, the independent forecaster expected productivity to grow by 22% over the course of this decade. It now thinks that will be more like 14.5%.

The US Congressional Budget Office, equivalent to the OBR, has revised forecasts down to a slightly greater extent.

And as that is the main, long-term driver of real pay, it means Britain's standard of living will improve from the recession, but at only two thirds of the rate we've come to expect.

So over the rest of this decade, the forecast for the average annual rate of growth in output has been lowered from 4.3% to 3.7%.

Pay is expected to grow by 3.9% per year on average, down 0.4% points from the November forecast, and mainly due to low productivity.

Similarly, profits (non-oil and non-financial) are due to grow by 3.5% on average, down from 4.6% forecast in November.

Running out of slack

This sluggish productivity continues to puzzle economists. As highlighted in my previous blog, the value of output per hour ought to be improving as the workforce deploys higher skill levels coming out of university.

And surely if employers are recruiting as enthusiastically as they have done in the past few years, that ought to be a sign that they are running out of slack with which to fulfil growing order books. But it's not.

One part of the explanation can be found in the oil and gas industry, which has productivity 12 times higher than the economy as a whole. Gas and electricity utilities are four times higher. (Tourism is roughly half as high.)

But it is these highly productive sectors that have seen the worst performance in productivity growth.

The energy utilities have gone from 5% annual growth in the years before the Great Recession to 5% average declines. Oil and gas, counted under "mining and quarrying" by statisticians, has seen annual declines of nearly 6% as production has slipped and costs have soared.

Manufacturing has held on to growth, but it's much slower than it was - down from 3.1% in the pre-crunch years to only 0.4% in the period from 2008 to 2015.

Higher wage, fewer jobs

For the big picture, across the British economy and between 1994 and the start of 2008, productivity grew by 1.9% in the average year. Remember: that was the key measure that drove up prosperity.

But between early 2008 and the third quarter of 2015, it fell before its sluggish rise. The OBR tells us the average year saw only 0.1% per year.

Economics logic suggests that this process will lead to the momentum in job creation running out of steam.

At 5.1% unemployment in the March figures (published three hours before Mr Osborne started his Budget speech), covering the UK-wide Labour Force Survey in November to January, that is forecast to fall to 4.9%, and then to rise a bit. That is partly because the higher National Living Wage, from next month, is expected to cost jobs.

(In Scotland, with higher unemployment in the March figures, it's now at 6.1%.)

The Budget as it affects Scotland

Talking of Scotland, a quick run through the other specific measures in the Budget.

The hike in the starting rate for income tax, and for higher rate tax from April 2017, presents a challenge to the Scottish government in its 2017-18 budget.

The basic rate threshold is controlled by Westminster, but its impact in Scotland falls on Holyrood. That is, at £11,500, there will be less revenue once MSPs have control over income tax.

So will there be compensation from Westminster, having pledged there will be 'no detriment' to Holyrood from decisions made by the Chancellor?

Or will the next Scottish government have to cut its cloth to lower basic rate revenue.

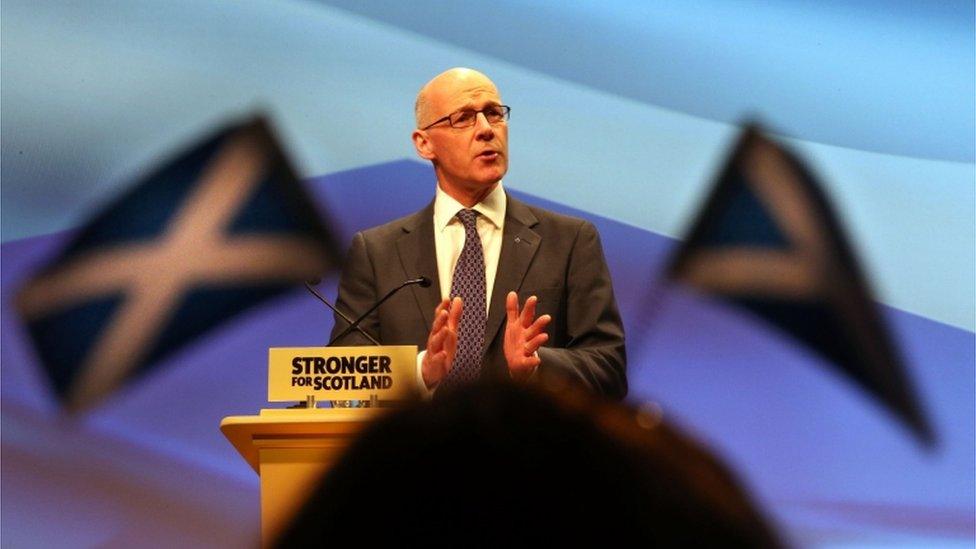

And what of higher rate tax? Will MSPs want to raise the threshold at which people starting paying 40% income tax to £45,000? Listening to John Swinney's reaction, it seems not.

But if he remains finance secretary, would he be content to see Scottish tax higher than the rest of the UK? He's sought to avoid that in the past.

The Scottish government has prided itself on its rates relief for small business. But George Osborne has gone much further on that, while also pegging future rate rises to a lower measure of inflation.

That means a sacrifice of tax revenue. Will Holyrood choose to do likewise, at a price?

There are changes to Capital Gains Tax and tax on dividends which are tricksy for Holyrood.

Because the tax rates for these are pitched well below the 40% higher rate of income tax, there will be an incentive for better-off business owners to take more of their earnings as dividends and capital gains than as pay.

That would divert the payment of tax - from Holyrood, which gets the income tax element, to Westminster, which gets tax on dividends and capital gains.

On oil and gas, it's easy to cut tax rates when hardly any profit is being made.

The "effective abolition" of Petroleum Revenue Tax removes a higher rate of tax on older oil and gas fields. And with Supplementary Charge cut from 30% to 20%, it means a flat rate tax on profits of 40%.

But due to high levels of investment and low profitability, the Treasury is seeing a reverse of the tax flow.

The OBR forecast, on which it is now working, points to around £1bn being repaid to oil and gas producers in each of the next few years.

Think how that is going to look in future publications of Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland, or GERS - the document that last week showed a near £15bn deficit for 2014-15.

Whereas oil and gas has delivered many billions of revenue to GERS each year, the forecasts suggests, for the first time, an annual cost to a Scottish treasury (if it were to control offshore revenues) of perhaps £800m.

A sugar levy is being introduced for public health reasons - giving the soft drinks industry a lead time of two years in which to lower sugar content, or pay a £500m annual price.

So far, it has cross-party support. It had been seen as un-Conservative to intervene in the market so directly.

But if a Tory Chancellor can meddle in the choices behind bad dietary habits, it opens the door to politicians at Holyrood - typically more interventionist - to target a broader range of choices.

- Published16 March 2016