Holyrood's incentives for growth: penalties for failure

- Published

Holyrood has avoided a £300m shortfall five years from now, as a result of Scottish government haggling over the allocation of funds from Westminster to Holyrood.

That is the calculation of public finance experts, in a report newly published by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

It has run its slide rule over the numbers, and calculates that is the likely gap between the block grant in 2021 if the UK Treasury had secured the funding formula it first pitched, and the one to which it eventually agreed.

That is seen by the Scottish finance secretary, John Swinney, as proof that the deal he struck with the Treasury is a fair one, and worth holding out for in the protracted Fiscal Framework talks.

Mr Swinney will be with Nicola Sturgeon as they set out plans for use of tax powers if the SNP is returned to government in May.

At the same time, Labour's Kezia Dugdale will attempt what Labour has failed to do in past elections, and come up with a convincing reform of council tax.

But behind their choices, about the use or non-use of some new and some older powers to alter the tax bill being levied by Holyrood, is the question of fairness in the distribution of funds through Westminster.

Diverging tax revenues

Working with Stirling University economists David Bell and David Eiser, the IFS has also looked at the new powers to borrow. They've concluded that they are quite constraining for Holyrood budgets, as they can only be used under specific circumstances of low growth, and lower than the UK as a whole.

The numbers also come with a big challenge, based on diverging tax revenues ... IF Scotland's growth rate lags that of the UK.

By following what it is describing that as a 'pessimistic scenario', the report says that Holyrood would be around £500 million short of its un-devolved funding within only five years.

And if that slower trend growth rate is continued through the next decade to 2031, the gap would be £2.1bn per year.

Nasty shocks

These figures reflect the risk that Holyrood will run from next year, when it takes on new tax powers, primarily over income tax.

While it continues to depend on the block grant for more than half the funding of devolved services, it is protected from nasty shocks hitting the UK economy and its tax revenue.

The block grant from Westminster is adjusted to take account of Holyrood's tax-varying powers

But it is exposed to the risk of a longer-term problem of relatively slow economic growth in Scotland, allied to faster growth in welfare spending.

That is because the block grant from Westminster is adjusted to take account of Holyrood's tax-varying powers.

The adjustment will take account of relatively slower population growth, and also a lower capacity for raising revenue per head through income tax (Scotland raises more revenue per head through Air Passenger Duty, and Landfill Tax, but only 87.5% of the amount raised per head on the far more significant tax on income).

Welfare growth

A small difference between Scottish and rUK income tax revenue growth could become significant. Under the pessimistic outlook, there would be a fall from 87.5% of the tax revenue per person across the rest of the UK (rUK) to 84% five years from now, and 77% after 15 years.

The scenario for welfare spending appears to be only slightly different, but it becomes a significant cost to Holyrood over time. The Stirling/IFS economists suggest that higher welfare spending per person in Scotland starts from 119% of the per capita spend for the rest of the UK (rUK), and a continuation of past trends raises that to 124% by 2031.

That means there is an incentive for the Scottish government to lower the growth rate of the welfare budget - or at least the part of it devolved to Holyrood.

Reap the benefits

But what if the gap in Scottish income tax revenue is closed over time? Although the IFS report indicates that its pessimistic scenario is the one based on actual outcomes over the past 17 years, in fact, Scotland's relative position has been improving.

If successful in growing the economy so that there is a continued rise in income tax revenue, Holyrood would reap the benefits of its own growth policies, and have a higher tax take per head.

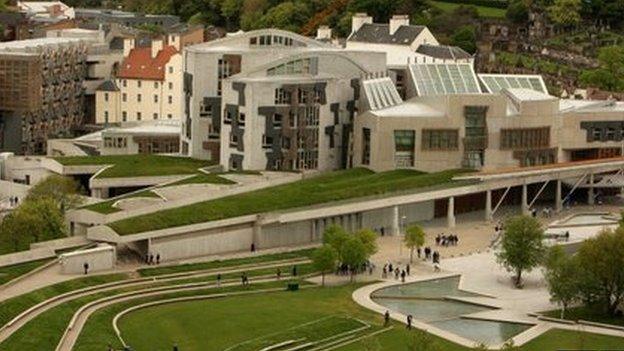

John Swinney believes the deal he struck with the Treasury is a fair one

The more optimistic scenario suggests Scottish economic growth could be 2.8% per year, while the UK averages 1.9%. By 2031, that would take income tax per head very close to the rUK level.

If, in addition, welfare spending were increased at a slower rate than the Department of Work and Pensions in London, then after five years, the results could be a boost of £700m more for MSPs to spend than they would have received under the existing block grant system.

A review of that funding formula is due to take place after 2021. If it stayed in place until 2031, the benefit to Holyrood could be an extra £2.4bn per year.

Compensation

What is missing from the IFS report is how to ensure faster economic growth or lower growth in welfare spending. That is for the political parties to argue over in the Holyrood election campaign.

But it might be worth noting, as the SNP joins others in setting out their tax plans, that a boost to growth rates for the economy (and therefore for tax revenue) is not usually associated with increases in tax rates. On the contrary, higher taxes tend to lower growth.

A further factor, highlighted by the IFS, is that Holyrood could pay an unexpected price for putting up tax rates.

What if people move their taxable income across the border?

As that would change people's eligibility for Universal Credit (which is based on post-tax income), the cost of the benefits bill would increase. And as that cost would fall on the DWP in London, Holyrood would have to compensate for it.

But what if tax cuts on one side of the border lead to "behavioural effects", in which people move their taxable income across the border or shift from Holyrood-taxed income to Westminster-taxed dividends?

Under the Fiscal Framework, which seeks to ensure there is "no detriment" from the decisions of one government on the finances of the other, there could be a claim for compensation.

That's if the impact is "material and demonstrable". But how to demonstrate it, and how to define "material"? That is open to dispute between the two governments.

And anyway, the IFS reminds us that the "no detriment" principle, arising from the Smith Commission report, was impossible to achieve in any framework.

Re-distribution

The IFS has looked at how this deal differs from other countries where tax powers are shared across governments - which is the majority of larger countries.

Most of them allow for some "equalisation" by central government, meaning tax gathered from the better-off areas are distributed to the poorer regions to ensure a roughly similar level of state provision of services or welfare.

What is unusual about the deal struck between the Treasury and Holyrood is that the "equalisation" element is built into the starting position, but is not continued in subsequent allocations.

In other words, the Barnett Formula - which has governed the allocation of funds to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland since the 1970s - was implicitly designed to compensate for being relatively worse off than England.

It is the starting point for the Fiscal Framework calculations. But if Scotland and the rUK diverge widely in future years, there is no counter-acting mechanism to ensure equal provision across the UK. The divergence would go on, unless the funding framework is changed.

Contradictions

If all this seems a cobbled together - a combination of pragmatism and fudge - then that's because it is. The Institute for Fiscal Studies is not impressed. It doesn't have to be this way, it is argued, "tacking on new features to a system that is widely seen as unsatisfactory".

There are questions of how much fiscal risk should be shared across the UK, or based on spending needs, or the capacity to raise revenue? Or even: should it be fair? Or based on law through which either side can appeal?

The Fiscal Framework doesn't answer any of these questions. It lacks a legal foundation or a clear set of principles.

And that is where the IFS concludes with the ironies of all this.

The UK government argued, in the independence referendum campaign, that devolved powers would be better than independence because risk can be pooled and shared around the UK. Yet it has fought hard to avoid the continued pooling and sharing of risk on these new tax powers.

The SNP government, meanwhile, has argued that if it can't have independence, Holyrood should have "full fiscal autonomy".

That would mean no pooling or sharing of risk. Yet Mr Swinney strenuously pushed in the Fiscal Framework talks for continued protection of pooling and sharing with the UK.

Contradictory? Yes. Confused? You're not alone.