Inflation takes off... full of helium

- Published

A Wolverhampton based company has plans to buy 12 Lockheen Martin airships

You may recall Richard Branson trying to set ocean-crossing records in a hot air balloon.

Perhaps you recall the Virgin boss dipped in the briny when his balloon crashed off the coast of Ireland 29 years ago.

To some of us - the less intrepid ones - it may have seemed like the hobby of a man with more money than sense. His interest in airships didn't get much beyond some very expensive advert hoardings.

But as this Saturday marks the hundredth anniversary of a First World War Zeppelin airship raid on Edinburgh, it seems an appropriate moment to note that Branson's adventures are now having a spin-off with a lot of commercial potential.

Market research points to sales of perhaps 600 airships over 20 years, with the oil industry as an early adopter.

A small group of the people who worked with Richard Branson on those projects are still in the balloon and blimp business.

This week they signed a letter of intent for their company, Straightline Aviation, to spend nearly half a billion dollars (£340m) on a 12-strong fleet of a new type of aircraft.

Off the beaten track

The project is in hybrid aviation - a combination of helium balloon, covering roughly the area size of a football pitch, and some powerful aero-engines. And it has some interesting implications for the oil and gas industry, as well as renewable energy and tourism.

Because new sources of fossil fuels are increasingly being sought in places off the beaten or metalled track, and because cost has become a big issue for the energy sector, hybrid aviation offers an alternative to building airports and roads.

The airship designed by Lockheed Martin in California is designed to carry up to 20 tonnes of cargo and 19 passengers, and to deliver it, with a range of up to 1600 miles, at 70mph.

It can land on sand, sea, in remote mountains or the remote ice and tundra of northern Canada and Alaska, where an airship removes the need to build ice roads each year.

Lockheed Martin claims its design has potential in inaccessible regions

The hybrid airship uses hovercraft technology for a soft landing and a grip to the land or water. While being heavier than air, its four engines ensure it remains in position.

And there are claims it can leave, tonne for tonne, only around a third of the carbon footprint of a fixed wing aircraft, and an eighth of a helicopter's.

So the 20 tonne payload is only the start. The US defence and technology giant has plans to push for a lifting capacity of 90 to 100 tonnes

Military surveillance

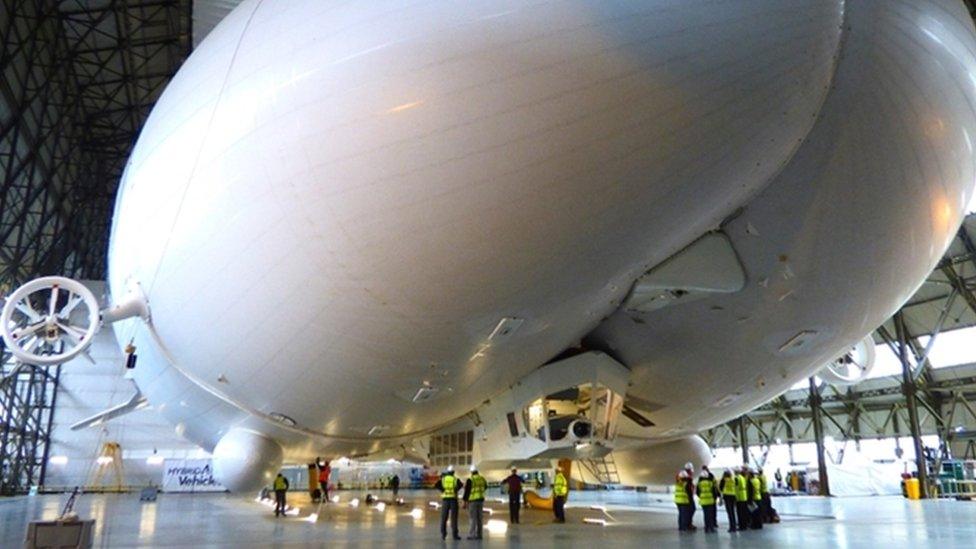

Another British company, based in Bedford, has reached prototype stage with a rival design. Hybrid Air Vehicles, or HAV, first unveiled the Airlander 10 two years ago.

If you join in crowd-funding it - and around 1000 people came up with another £500,000 only last week - you can join the Airlander Club and get a hard-hat tour of the hangar it currently occupies.

Getting to its maiden flight has taken longer than expected, but it could happen within weeks.

The Airlander 10 is due to be officially named by the Duke of Kent later this month

At 92 metres (300 feet), Airlander 10 looks and floats more like a conventional airship, with powerful positioning engines. For now, it is aimed more at passenger transport. You can probably imagine the potential for sightseeing in tourism honeypots.

Along with the heavier-lift Airlander 50 design, it has other potential and very significant uses. It could be adapted to stay at high altitude for up to five days, providing military surveillance and airborne co-ordination, or up to 21 days in its unmanned mode.

Or it could monitor movements across a border (saving Donald Trump a lot of dollars over the big Mexican wall he's planning as president).

Military deployment was where the project began more than ten years ago. Much of the HAV funding came from the US Government, where the US Army wanted a Long-Endurance Multi-Intelligence Vehicle.

However three years ago, Pentagon funding was withdrawn as President Obama and Congress battled over the government budget ceiling. So HAV went out to research markets beyond US Army orders, and concluded in 2014 that there could be demand for 600 airships over 20 years.

Carbon footprint

Northern North America is where Straightline Aviation intends to locate the first of its 12 Lockheed Martin airships. The Wolverhampton outfit is led by long-time balloon and airship enthusiasts, drawn together in Sir Richard Branson's stable of airborne adventurers, led by chief executive Mike Kendrick.

This week's letter of intent was signed while Lockheed Martin seeks regulatory clearance for the aircraft. The first of its production run is due for delivery to Straightline in 2018.

If the Midlands company gets lucky, that could be around the time that the current sharp cuts in oil and gas exploration lead to a supply crunch, and a rise in the price of energy.

And while there's a lot of northern forest and tundra to be explored in North America, there are also remote Middle East deserts and south-east Asian islands.

And the recent big finds in oil and gas have been off the coasts of Africa, which offer the industry huge potential but not much infrastructure.

If not for oil and gas, the hybrid airship could offer opportunities for renewable energy - getting turbines offshore or onto hilltops without the need for expensive road infrastructure or helicopter lifts. Or it could transport solar panels into the desert.

The chief operating officer of Straightline Aviation, Mark Dorey, cites a striking statistic that half the world's population is not connected by road.

So connecting them by air, this new take on inflation floats big possibilities for commercial, economic and development benefits.

- Published1 April 2016