Private money, public controversy

- Published

It used to be the hottest of topics in Scottish politics. Three Holyrood elections ago, in 2003, the BBC's "issues poll", external found that the private financing of public services was the most unpopular policy, and fourth on a list of concerns.

(As you're probably wondering, and contrasting with 2016, "bobbies on the beat" was top, followed by nurses pay.)

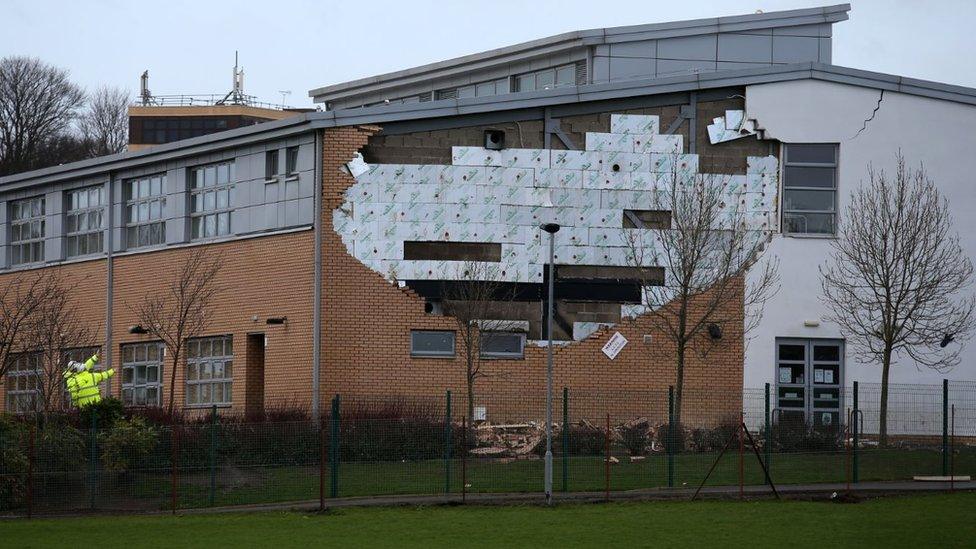

Private finance of public services has intruded into this year's Scottish Parliament elections in the kind of intervention that no-one could have foreseen - more than 7,000 Edinburgh pupils unable to attend school because of a risk that the walls might tumble on them.

If you're in the business of government (or, indeed, the government of business), this is a serious issue. Parents need to know that children are safe at school. So does everyone else.

Sorting things out is a priority. But in election season, so is the placing of blame.

Is this a sign of the failure of the private financing of school buildings? Could the private funding model that is now being used by government ensure this could not happen?

Does conventional procurement offer any better protection against walls falling down?

To get at answers, some other questions might first be useful, to explain private finance of public assets. Here are some of them:

How do we fund the building of schools and other public assets?

Some projects are funded by conventional means. Government (or a council or a health board, Police Scotland or the Scottish Prison Service, etc) commissions a design, and after competitive bidding, a building contractor to build it. Once it is completed, it is handed over for the public agency to operate.

If something goes wrong with the design, then the client or designer takes responsibility. If the building is faulty, the contractor retains responsibility for lots of things over 12 months, and long after that for latent defects.

And what about private finance?

I was coming to that. Over the past 30 years, private finance has been deployed to design, build and to operate assets.

Government (or its agencies) negotiates a contract with private companies to build an asset such as a school. The private companies typically form a consortium comprising a construction firm, facilities manager and investment funds.

A lot of the profit from private finance is derived from managing the facility

For an agreed monthly fee, and usually for 25 or 30 years, the consortium provides and maintains the infrastructure. A lot of the profit from this is derived from managing the facility.

That can mean facilities management of a school or clinic, but not the service in it, or it can extend to running every aspect of a prison.

What is the appeal of the private finance option?

With constrained capital budgets, it spreads costs over decades, and pushes the cost onto the revenue budget - as if renting the building and paying for it to be maintained and factored.

It is also argued that the private sector brings tougher financial disciplines, so that projects are delivered on time, and the risk of going over-budget is transferred away from the taxpayer.

But transferring risk comes at a price, and that is factored into the monthly payments. And as it is mandatory for public authorities to provide services such as schools and hospitals, they always have to step in as a last resort. So an element of risk remains with the taxpayer.

Some contracts have suffered from inflexibility, or hidden extra charges.

Critics of private finance point to high lifetime costs for government, and big profits for financiers. The secure future stream of payments is an asset that can be sold in a secondary market, and some have changed hands for obscene sums.

How has private financing of public assets changed over time?

In the 1990s, under Conservative government, the first Private Finance Initiative (PFI) projects were particularly controversial. The Skye Bridge, for instance, was seen as very poor value for the public and toll-payers. The contract was eventually bought out.

The Edinburgh Royal Infirmary deal was notoriously inflexible. The business model relied on charging patients and visitors, for instance for use of a television and for car parking.

The Labour government came to office in 1997 promising to end the excesses. But it liked the integration with private finance, at a time when renewal of schools and other public buildings was overdue.

The Skye Bridge was seen was seen as very poor value for the public and toll-payers.

Under Tony Blair, Labour re-badged the policy as the Public-Private Partnership (PPP). In Scotland, the party embraced the opportunity to have a huge school building programme without needing the capital budget to pay for it, along with LibDems once in Holyrood coalition.

Meanwhile, public sector officials were gaining experience in negotiating contracts. The early deals had been done with little understanding of financial risk.

The Internal Rate of Return, reflecting that risk, was very high in the early days. As negotiators on both sides got experience, the typical IRR fell sharply.

Bidding was getting more competitive, and as profits got tighter, some consortia even went bust.

The SNP was against PFI-PPP, so surely it ended this when it came to power?

Yes. And no. The Scottish National Party came to power in 2007 with a promise of a new funding mechanism.

Something called the Scottish Futures Trust would use council borrowing powers, bundled up for national projects and issued as bonds.

It didn't work out that way. The Scottish Futures Trust was introduced by the SNP government, but it looks very different to the pre-election plan.

It is an organisation which offers project funding expertise for the public sector.

It commissions hubs - buildings shared by public organisations to improve efficient use of taxpayer pounds.

This year, it intends to complete 21 school buildings or upgrades, start construction of 19, and start planning for 19 more.

It is an arm of Scottish government policy, for instance looking at ways to expand capacity for nursery education and childcare.

It has sought to reduce design costs with model buildings, as guidelines for others throughout Scotland.

Re-use of designs has been one of the ways in which private financiers have reduced cost - though it looks less clever now in Edinburgh, where repeated designs may have led to repeated mistakes.

So the SNP didn't introduce a new model for funding?

It was new-ish. The Non-Profit Distributing model had already been tried for projects in Argyll and Bute and Falkirk. And the incoming SNP government embraced it.

NPD is similar to PFI-PPP, with one difference in its design. Contractors do not have ownership of the assets. That means they provide finance as debt, in return for a predictable flow of income. Without equity, they lack the opportunity for unlimited profits.

But finance experts point out that equity had already become a minor part of the deal, as the rate of return was brought down.

And financiers expect the same Internal Rate of Return that they could expect for their money if invested in English PPP.

If they don't get that as return on equity, they'll increase the IRR on the debt to get to the same numbers, and the same profitability.

How extensive are these privately-funded projects, and how much is being paid out for them?

The revenue cost for all of the PFI-PPP projects to which the public sector is committed runs to just over £1bn this year. That is just under 4% of all spending, while the SNP has set a ceiling of 5% of spend.

Roughly a third of that is in education, and just under a quarter is in health and sport.

Scottish government figures issued last July show more than £6bn of capital value to these privately-funded projects, 8% of which was then NPD (but growing quite fast).

Thirty-eight schools accounted for £3.4bn, 28 hospitals and clinics for £1.3bn.

The next big tranches were in transport, at £610m, and waste water, at £562m.

So what could all this have to do with walls falling down in Edinburgh schools?

Perhaps not very much. We know from problems in Glasgow's Lourdes Primary that a similar problem has been found in a conventionally procured building.

We know from the Holyrood Parliament building project that conventional procurement can also turn into a fiasco.

Schools closures in Edinburgh were prompted by the collapse of a wall at Oxgangs Primary

It could be that work on the Edinburgh schools was done too hastily, or with the wrong materials, in order to cut costs.

But if you were a builder cutting corners, you probably wouldn't start with wall ties.

The self-certification of building completion looks a likely line of inquiry, once one gets under way.

But it's not clear there is any connection between that and the source of funding. That building standards regime operates equally across building sites.

The only difference between conventional procurement of a school and private finance is one that points to a higher chance of shoddy workmanship in a conventional contract.

That is, a construction company contracted to be responsible for maintenance over 25 years has an incentive to build to a higher quality than otherwise, so as to minimise cost over that term.

So who is responsible for the Edinburgh schools scandal, and who will pay for it?

The political blame game will surely go on, arguing over the funding methods. An inquiry ought to shed some light on whether there was any connection. But there's no evidence yet.

PFI, PPP and NPD have kept a lot of the contractual detail private. But there's not much doubt the private consortium will be held liable for the costs of repair and of disruption.

How much will they pay out? Well, the construction industry is quick to resort to lawyers to fight over such costs. It seems a safe bet that this will land up in court, or in arbitration.

And one of the questions for parents is whether they too can claim the cost of disruption to their family, childcare and working lives.