Whatever happened to the Saltire Prize?

- Published

A decade ago, a wave of excitement swept over the renewables industry as the Scottish government announced a £10m prize for innovation in marine energy technology.

The Saltire Prize was billed as the world's largest award of its kind.

Its aim was to accelerate the commercial development of wave and tidal energy technology.

But 10 years on, the deadline for the prize has come and gone - and no-one has collected.

That came as no surprise when the competition officially ended last summer.

As far back as late 2015, the Scottish government acknowledged the "likelihood that...it cannot be won", after firms taking part found they could not meet the criteria.

What were the criteria?

The prize guidelines stated a team had to demonstrate:

in Scottish waters

a commercially viable wave or tidal stream energy technology

that achieves the greatest volume of electrical output

over the set minimum hurdle of 100 GWh

over a continuous two-year period

using only the power of the sea.

Meet the challenge

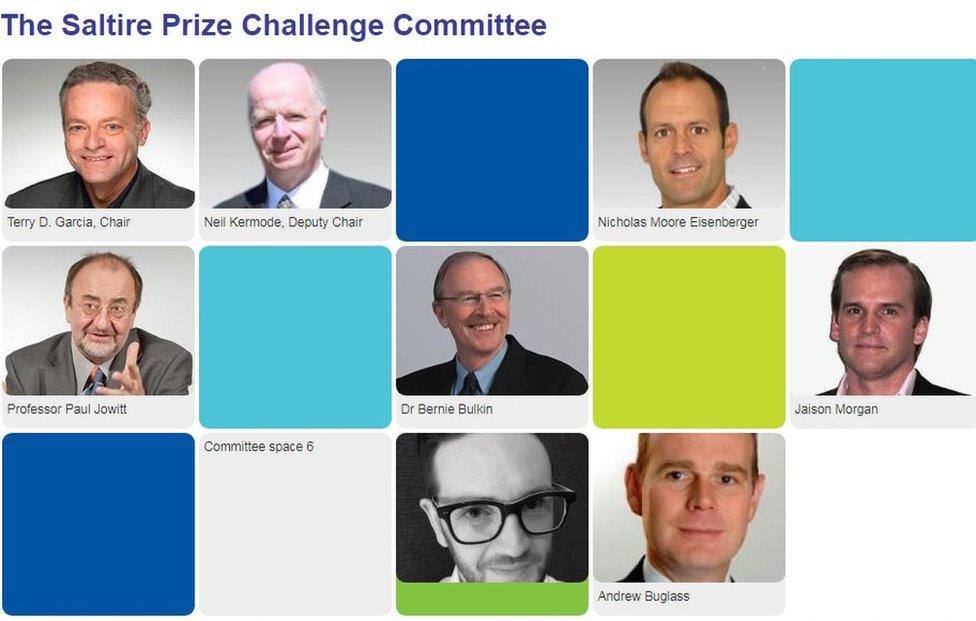

By 2013, five companies were in the running for the big prize, overseen by an independent panel of experts sitting as the Saltire Prize challenge committee.

But as the competition progressed, it became increasingly clear that the entrants were struggling to meet the challenge.

In 2014, one competitor - wave power firm Pelamis - went into administration.

It was followed a year later by another - Aquamarine Power - which also slid beneath the waves.

As one industry insider close to the competition put it: "The wave technology wasn't reliable enough - it had too many moving parts and wasn't robust enough."

The company behind the Pelamis wave energy device slid into administration in 2014

Aquamarine Power, which developed the Oyster wave energy converter, collapsed in 2015

In response to questions by BBC Scotland this week, a Scottish government spokesman said the marine energy industry had "taken major steps forward" since the Saltire Prize guidelines were developed in 2008.

He added: "But, despite a number of high profile successes in the sector, the path to commercialisation is taking longer and proving more difficult than initially anticipated not least due to a lack of dedicated, or ring-fenced, market support mechanisms for commercial-scale marine energy projects.

"As a result, no competitor was able to meet the original prize deadline of June 2017.

"However, the (Saltire Prize challenge) committee is considering options for reshaping the prize to better reflect the circumstances of the wave and tidal sectors, so that this can continue to provide an incentive to drive innovation in Scotland."

Saltire Prize timeline:

April 2008 - Former first minister Alex Salmond announces the award

March 2013 - Five companies are in the competition

November 2014 - Competitor Pelamis calls in administrators

October 2015 - Competitor Aquamarine Power calls in administrators

November 2015 - Scottish government says the Saltire Prize challenge committee, which oversees the award, is "considering options for reshaping the prize"

April 2016 - Revised prize options, drawn up by trade body Scottish Renewables, are shared with the committee

January 2017 - Committee members ask for "up-to-date analysis" of the marine energy industry to inform their deliberations

April 2017 - Consultants appointed to produce a report on the current state of the industry.

September 2017 - Scottish government says it expects to share the report with the committee in early September 2017

February 2018 - Scottish government says that report will be published "shortly" before being put to the committee for consideration

The idea of "reshaping" the prize came long before last year's competition deadline.

In November 2015, former Energy Minister Fergus Ewing told the Scottish Parliament that the prize challenge committee was considering options for reshaping the prize "to better reflect the circumstances of the wave and tidal sectors".

In response to questions from Scottish Liberal Democrat energy spokesman Liam McArthur, he said: "It is absolutely right to review the prize in the likelihood that, because of the criteria set, it cannot be won."

The review appears to have made little progress since then, with the challenge committee meeting only a handful of times - none of which was held in person.

Liam McArthur has raised the Saltire Prize with Scottish ministers on several occasions

In September 2017, Energy Minister Paul Wheelhouse informed Mr McArthur that Scottish government officials had had "three conference call meetings and a series of email exchanges" with members of the committee since November 2015.

He also revealed that revised prize options were shared with the committee in April 2016, following an informal review carried out by trade body Scottish Renewables.

Mr Wheelhouse added: "However, at the most recent meeting in January 2017, committee members asked for an up-to-date analysis of the marine energy industry to inform their deliberations.

"Following a competitive tender process, renewable energy consultants Aquatera and Caelulum Limited were appointed in April 2017 to produce a report on the current state of the industry.

"We expect to have a final report to share with the committee in early September 2017."

That report has still to see the light of day.

A Scottish government spokesman told BBC Scotland this week that it is due to be published "shortly" but stopped short of giving a specific date.

BBC Scotland tried to contact the members of the challenge committee last week to ask what progress was being made. Those who responded referred inquiries to the Scottish government.

However, veteran environmental campaigner Jonathon Porritt, who was listed on the Saltire Prize website as a member, responded by email to say that he "actually came off the challenge committee some years ago".

His name and photograph were removed from the website hours after BBC Scotland informed the Scottish government.

Eight members now "remain active" on the committee.

BEFORE: Earlier this week, Jonathan Porritt was listed on the Saltire Prize website as a member of the prize challenge committee

AFTER: Mr Porritt was removed from the website after BBC Scotland made inquiries with the Scottish government

The Saltire Prize website is still providing out-of-date information.

In the "About Us" section, it states that "Fergus Ewing MSP, the Minister for Business, Energy and Tourism, has lead responsibility for the Saltire Prize". He left the role in May 2016. The current energy minister is Paul Wheelhouse.

Meanwhile, BBC Scotland has learned that other projects related to the prize have also been halted.

Skills Development Scotland confirmed that the Junior Saltire Prize, which it sponsored, was "put on hold" last year.

That prize was set up in 2011 to raise awareness among primary and secondary school pupils of the potential of marine renewables.

The Scottish government responded by saying that the junior prize was "being considered as part of the review of the main Saltire Prize".

It gave the same response to questions about the Saltire Prize Medal - created to recognise "outstanding contributions" to the development of marine renewable energy - which has also been put on hold.

'Dead in the water'

Mr McArthur, whose Orkney constituency includes the European Marine Energy Centre, told BBC Scotland: "I recognise the initial value of this initiative as a statement of intent and still firmly believe that Scotland can and must lead the way when it comes to marine renewables.

"However, everyone in the industry has known for some time that the prize is dead in the water.

"After years of ducking and diving, SNP ministers must now come clean.

"They need to explain how they plan to invest the funding in ways that will actually make a difference in enabling Scotland to realise its potential in this area."

- Published28 October 2015

- Published21 November 2014

- Published28 August 2012