Europe's Galileo: Britain's blast-off

- Published

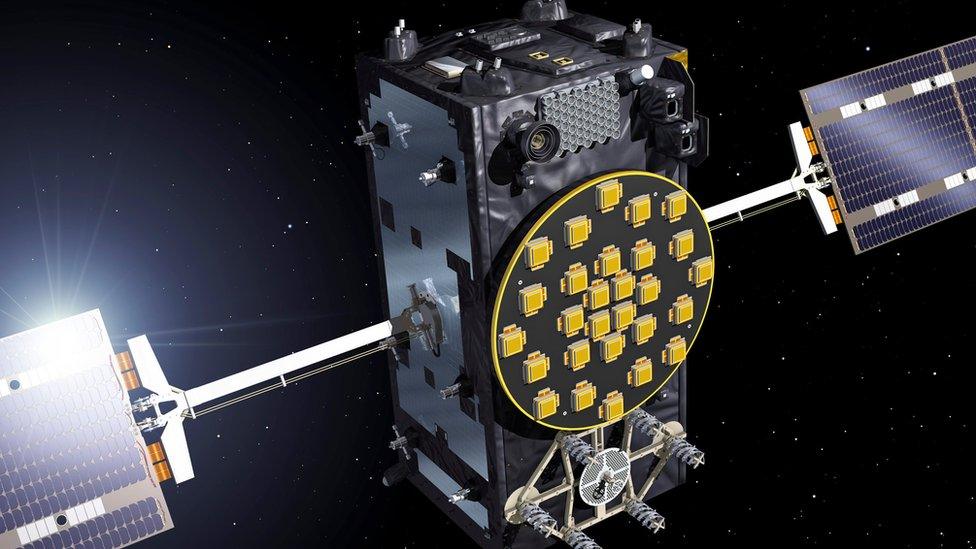

The European Union has put together Galileo as its own network of satellites

The battle of Brexit has been raging at Westminster this week. But one of the subjects that's infuriating Brexiteers is going far over our heads. And if you've got a smart phone, or sat-nav in your car, you may already be dependent on it.

We often call this GPS - global positioning system. But increasingly, we should call it Galileo. That's because GPS is controlled from the Pentagon in Washington. It's an American military-based satellite system.

The European Union has been putting together Galileo as its own network of satellites. It's full of British expertise, but Brexit Britain looks like losing its privileged access to Galileo's secret inner workings.

I've been finding more about it, from those who have co-ordinated the commissioning from Brussels and from Professor Malcolm MacDonald, an expert in satellite technology and space policy at the University of Strathclyde.

How does this technology work?

An artist's view of a Galileo full operational capability satellite

The systems are all similar in concept, requiring a minimum of 24 satellites in quite a high orbit to get the maximum reach over the earth's surface. These send out very, very accurate time signals.

Wherever you are, your phone or satnav picks up signals from at least three different satellites, which orbit the earth on different axes - something like those illustrations of an atom where electrons spin around a nucleus.

Put the three together, compare the different lengths of time it has taken for the signals to reach your mobile phone, and it can compute where you are.

A recently bought phone, or one with updated software, will be Galileo-compliant, so it will draw on GPS signals plus Galileo and possibly also from a Russian satellite network. They interact, and the more signals, the more accuracy you should get.

How accurate is Galileo?

GPS is accurate to within about 20 metres. Galileo is designed to improve that, to around one metre. The restricted system, for use by governments, should be able to reduce that to around 25cm.

Does that give it more uses than GPS?

The satellites don't monitor which devices are using the signal, but there is part of system that can pick up search and rescue signals. So that's of use for maritime search, or remote mountains, or if a car crashes off the road.

Every new car model launched in Europe is required to have a Galileo-linked beacon, which should be activated as soon as an air bag is inflated. Emergency services will instantly know where an accident has taken place. The estimated time of getting to a maritime Mayday call can be sharply reduced.

The uses for autonomous vehicles have yet to be developed, but it's clear that satellite technology will be an important part of future road transport - both to guide cars and to manage traffic systems. It also has potential for road pricing.

Malcolm MacDonald says the crucial difference is that we can trust Galileo better than GPS, even to land a plane where there's no ground radar. That element of its capability is being used by 350 airports in Europe, and also deployed in less developed areas of the world, where communications are poor.

Already, GPS and Galileo have become a vital part of finance. In trading, it matters a lot that there is an electronic record of when transactions have taken place. The electronic date-stamp from the satellite navigation system is recognised by all parties to contracts as the reliable industry standard.

Then there's agriculture. Another European Union network, called Copernicus, provides earth surveillance. It can tell a farmer about different growing conditions across a field. It can, for instance, highlight an area that needs a higher level of fertiliser or pesticide than others.

Satellite navigation can then be used to direct farm equipment - in some cases, autonomously - to the point of need, saving on cost and environmental impact.

How close is Galileo to completion?

Galileo satellites are now launching on Europe's premier rocket, the Ariane 5

The first satellites were put into orbit from 2013. There are now 22 in orbit, and 18 of them have become operational. That gives it around 80% global coverage.

Another four satellites are being prepared for a rocket launch from French Guiana next month. Once they have been fully deployed, from 2020 the system should be complete, and there will be two spare satellites in case others run into technical difficulties.

From around 2023, a replacement programme will start. Due to stresses of heat and cold, the satellites have an estimated 10-year lifespan.

Haven't the British done some good business out of this project?

Almost all the payload - the brains of the satellite - are built in Britain, which is a world leader in small satellites. Glasgow's got a good chunk of that market but not for Galileo.

The other big spend is on the components - the solar panels, the casing, the rocket systems, where the Germans, French and Dutch have done well.

But if we go back to 2002 into 2004, when Galileo was first being discussed, the British - backed up by Germany and the Netherlands - were strenuously arguing against it.

They argued it was a classic, daft, Euro-waste of money and, literally, of space. With encouragement from Washington, the British were asking why Europe couldn't simply rely on the American GPS system.

They didn't realise then how quickly people and the economy would become dependent on satellite navigation, on how widespread its applications could be, or on how positive the satellite sector could become for the British economy. Nor did they foresee that Donald Trump would become US President and could switch off GPS on a whim.

When the programme was first discussed, there was talk of it being privately financed. That didn't happen, as providing a free service doesn't produce an income stream.

There were discussions with Russia and China about working on this network with the European Union. But in Moscow and Beijing, they decided to go and make their own, military-led systems.

Given the change of tone from the Kremlin, and concerns about China's acquisition of technology, it's hard to imagine those partnerships working smoothly now.

So the European Union is happy with the system it has bought?

The European Commission certainly sounds that way. It has spent around 10 billion euros so far, on satellites, launches, and building ground stations (the British and French have some helpful far-flung outposts and former colonies that can be used for that).

And they're so happy with it that they announced this month that they intend to spend a further 16 billion euros from 2021 to 2027. That's as much as they have spent from 2005 to 2020. The absence of the UK from paying into the budget isn't going to slow them up.

That money sustains the Galileo systems, paying for some replacement satellites as they wear out. It also supports the Copernicus network of satellites, which provides earth surveillance - of farming, land planning and pollution monitoring, and it has uses in handling natural disasters.

The commission reckons that 80% of new phones on the market are Galileo-enabled. Just two years ago, there was one manufacturer linking with it, a small one in Spain.

That did not take regulation. It's in the manufacturers' interests to deploy the technology. It did, however, require legislation to force car manufacturers to adopt the locator beacon technology as standard. And once on board all cars, it's an important step towards a satellite-based system for smart traffic management and autonomous cars.

Britain's being denied access to at least part of this satellite system. Why?

The UK is being denied on two grounds. One is the restricted part of the system, of particular interest for military uses. Britain has a lot of them. Think missile targeting.

That element of Galileo is only for EU members, and when Britain is not an EU member, it will have to negotiate a special deal to use the system. Norway and America are already in talks to do that, and the talks have been under way for more than two years.

I was in Brussels earlier this month, asking around about this, and I was told this makes the British - Brexiteers and remainers alike - more incensed than almost anything else in the negotiations. (So far.)

Britain helped pay for it. It's been important to building it: "So be reasonable, chaps."

In Brussels, they're saying: we're governed by rules, and look at the words - non-EU members, or "third countries" don't get automatic access to the high security functions.

The other dispute is the ban on Britain being able to bid for work on the secure aspects of future EU satellites. So SSTL, the Surrey-based subsidiary of Airbus that makes most Galileo satellite payloads, is reported to be planning a move of its production to the continent.

The UK government has tabled a proposal to share the system post-Brexit, but the other 27 members this week chose to continue while cutting the UK out of procurement. That brought a warning that the British could seek to frustrate the process and increase its costs.

Could the UK have its own satellite network?

That was being urged on ministers in the House of Commons this week. It would be an expensive option.

It could be cheaper to do this on a one-country basis, and some lessons have been learned from the Galileo process. But it's not expected to leave much change from £10 billion.

The British clearly have the know-how. At a price, it can hitch a ride on another country's rocket.

Japan and India have their own regional systems, with satellites positioned above those countries, so that might be an option.

But it looks like we might have spending pressures closer to home.

- Published13 June 2018

- Published14 May 2018

- Published10 May 2018

- Published9 May 2018

- Published25 April 2018