Modelling the economic impact of Brexit

- Published

The economic impact of Brexit has been keeping the modellers busy. On one day, the UK Treasury and Bank of England both published estimates of how different Brexit arrangements might be expected to go, the day after the Scottish government updated its figures.

The National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) is doing likewise, following the International Monetary Fund. So some questions:

What are they telling us?

They all differ, depending on the assumptions fed into the models. But they all agree - that any kind of Brexit is going to mean lower output from the UK economy into the long-term, when compared with the trajectory of the economy if the UK stayed within the European Union.

What they also show - or at least, none of them disagree: a hard Brexit or "no deal" Brexit would be worse for economic output than any other variety of Brexit.

So the economy can be expected to grow. But the Treasury reckons there could be a 3.9% gap, after 15 years, between the output of the economy if the government's White Paper from July were to be implemented, and unchanged links with the EU.

Compare that with the 9.3% gap between EU membership in 2034 and a "no deal" departure from the EU.

The Scottish government has a different take, updating its numbers from earlier this year, to say the average Scot would be £1,600 worse off by 2030, under the prime minister's plan.

That equates to having 7.4% less real disposable income, while business investment would drop around 7.7%. The same figures were related to a Free Trade Agreement, when they ran the numbers in St Andrew's House earlier in the year.

Isn't the choice between the Prime Minister's deal and 'no deal'?

That's what Theresa May says. Others disagree, saying that voting down her deal should lead to other options being brought forward, or re-entering negotiations with Michel Barnier.

But because the PM wants to focus minds on her version of the choice, the Whitehall figures are also presented as a positive premium of the White Paper or Free Trade Agreement when compared with "no deal".

Thus, by starting from a really bad "no deal" baseline, the White Paper option can be made to look like it will deliver a 6.9% boost to the economy, or a typical/average Free Trade Agreement would add 2.7%.

What does the White Paper have to do with it? Why not model the deal that UK negotiators struck with EU leaders?

The modelling that refers to the White Paper was by Whitehall economists. It looks like they were unable to make assumptions about the deal being put to MPs on 11 December, because so little is known about the way it might turn out 15 years from now. Being in the government machine, it might have seemed politically unhelpful to say so.

The deal being pushed by the prime minister is detailed on the transition arrangements, but leaves a lot to be negotiated beyond that. The Treasury economists looked at outcomes that could veer towards a typical Free Trade Agreement (no tariffs, but customs barriers, something like the EU's new relationship with Canada) or membership of the European Economic Area (like Norway). The Canadian-style option would carry a higher cost to economic growth (a bigger hit to its potential) than the Norwegian-flavoured one.

Why do they look 10 or 15 years ahead?

That's reckoned to be the time it might take for the new relationships between the UK and its trading partners to settle into some sort of pattern. So take note, all ye who say "just get it over with". Whatever happens, this will take years to get it "over with".

The UK Treasury model includes some heroic assumptions about the speed at which Liam Fox's Department for International Trade could do deals with other countries. No other country has succeeded in striking so many deals so quickly.

An important point arising from the models, including the Scottish government and the Treasury, is that the effects change over time. So in Scotland, over the short to medium term, the first years would be mainly affected by trade and tariff barriers. But as businesses adjust to that, the role of net migration begins to have a more significant impact, and likewise productivity.

Lower net migration can be expected to reduce the rate of growth. And less inward investment means less of a contribution to productivity improvements from new processes and ideas coming in from abroad.

The St Andrew's House economists say that, by 2030, productivity would account for 60% of the difference in GDP between a "no deal" Brexit and EU membership, while migration would explain 26% of it. That leaves only 14% to be explained by the more obvious barriers to trade, such as tariffs.

And this assumes no change to the way the EU Single Market operates. If, for instance, Brussels deepens the integration of financial services, which it would like to do, that could have a big impact on growth within the EU over the next decade. It would widen the growth gap with the UK.

Would there be different impacts around the UK?

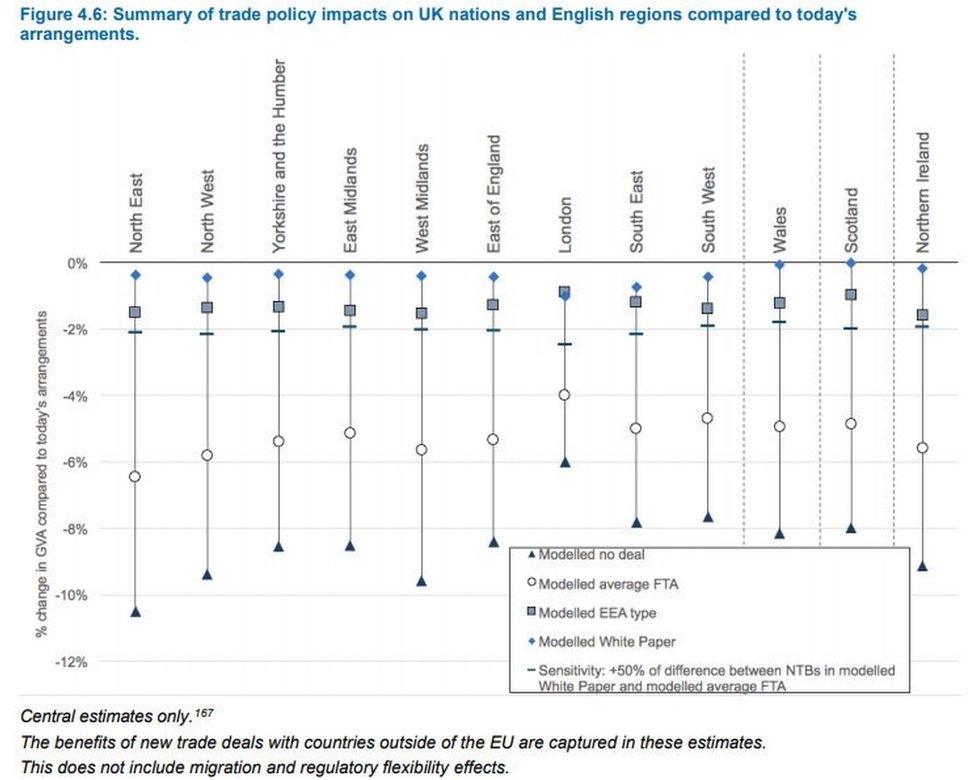

Almost certainly, yes. The UK Treasury model takes a look at this, and reckons that the regions of England with the most dependence on exporting manufactured goods (for which they import some components) would be hardest hit by a hard Brexit. That includes north-east England and the West Midlands, where the impact on the car industry and chemicals would be felt strongest. For north-east England, "no deal" looks like a 10.5% drop in output compared with EU membership

Some Brexit arrangements could hit services harder, and they would mean worse news for London, with its financial services powerhouse. But overall, London could be expected to take the least harsh impact from most types of Brexit, and particularly the "no deal" variety.

The south-east and south-west of England would be less hard hit as well, followed by Scotland.

The Treasury model indicates a "no deal" Brexit would mean an 8% hit to Scottish output after 15 years. An average or typical Free Trade Agreement with the EU would come at a price of 5% compared with EU membership.

Membership of the European Economic Area, like Norway, would leave Scotland trailing 1% behind its EU potential. And here's the unusual thing: Scotland is the only part of the UK which would have the same output under the UK Government's White Paper, as it would with EU membership.

Why does it do relatively well, or relatively less badly? Energy, it seems. Whether oil or renewables, that sector is thought to be relatively protected from the disruption of Brexit.

Why should we believe forecasts? Aren't they always wrong?

They're not forecasts. They are the application of models, based on our current understanding of the way the economy works. These brainy economist types can tweak the model to increase the level of immigration or reduce the extent of customs delays, and thus they get to a lot of different results. And yes, they are almost always wrong, but they offer some guidance as to what can be expected.

Many of the forecasts that have been way out of whack in the past decade may reflect the lack of current understanding of the way the economy works post-crash.

When these models spit out one figure for a set of post-Brexit circumstances, that is the mid-point figure for a range of outcomes. For no deal, for instance, the impact on output of changes to trading arrangements is estimated at 7.6%, but that is in the range between 9% and 6.3%.

What none of the models offers is the factoring in of other changes that might take place in the world or UK economies over that time. And you can be sure that lots will take place; trade wars, shooting wars, tax cuts and hikes, changes in technology, extreme weather events, commodity market volatility. Also, if things are going badly, the Government can take decisions on taxation, spending or borrowing that can alter the performance of the economy.

They do seek to look into the future however, and those who wish to dismiss them can point to predictions of calamity immediately following the 2016 Brexit referendum. In the short term, the more alarming prospects proved to be wrong. George Osborne, then the Chancellor, was one of the most prominent exaggerators.

So what happens if immigration is tweaked?

Migration is seen by economists as a way of boosting output, or Gross Domestic Product. Immigrants are more likely to be of working age, and more productive than others. If there were no change to the current flows of people across the North Sea and Channel, the Treasury reckons on a 4.9% hit to GDP if there were a Free Trade Agreement, compared with EU membership.

But if the government implements change to migration policy to reduce inflows of European workers to a net zero, that would mean a 5.4% hit to output per capita.

What about those who say Brexit will be to the benefit of the economy?

Even the most enthusiastic Brexiteers concede that the short-term impact on the economy will be disruptive, and it will take a knock. They then look to two main factors that could help boost the growth rate to a higher level than the EU.

One is de-regulation. With more flexible working patterns, and fewer regulatory requirements - making it cheaper to hire workers for instance - businesses would be able to grow faster.

That assumes that such de-regulation is politically possible. The problem that it could face is if public opinion turns to being protective of health and safety or of employment conditions which originated in the European Commission.

Alternatively, a trade deal with the EU may require the UK to continue having such employment conditions to ensure a level playing field - which was the point of introducing them across the EU in the first place.

The other factor championed by Brexiteers is the possibility of alternative trading partners providing a platform for faster growth - if, for instance, UK businesses can tap into the rapid growth of Asian economies, or easy access into vast North American markets.

What they have been poor at proving is that the European Union has held back UK businesses from trading. Scotch whisky or salmon, for instance, have had easy access into markets around the world, while the UK has been in the EU.

Striking trade deals with other countries tends to take a long time. It requires expert negotiators, and Britain's have been shown to be inexperienced.

Meanwhile, in the age of economic nationalism, championed by President Donald Trump, the case for protectionism is being heard much more loudly than the case for making concessions to do deals and increase the flow of free trade.