Brexit: out of the frying pan

- Published

World Trade Organisation tariffs could effectively block meat exports to the European Union, and would boost food price inflation.

The Scottish government is warning that removal of those tariffs by the UK could open the floodgates to cheap imports.

The food and drink sector is warning of a potential £2bn hit to sales, and it is being held back by the freeze on investment.

Amid the noise and confusion of Brexit, between parties and parliaments, here's a small example of the complexity that comes with "taking back control".

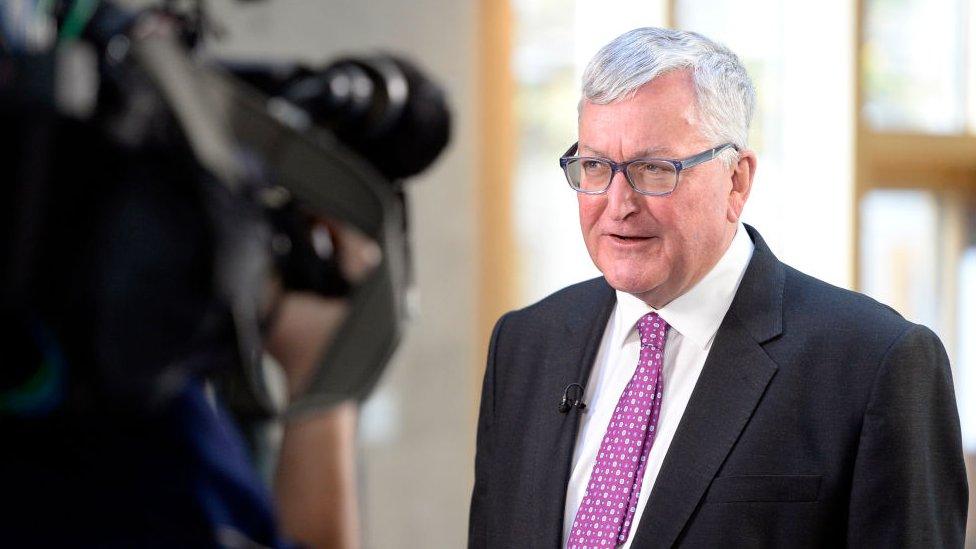

It comes from Fergus Ewing, the Scottish government secretary responsible for agriculture.

It has to do with knocking down barriers to trade, but at great risk to farmers.

To explain, if there's no deal on a transition, exports of meat can be expected to face some of the highest tariffs. On agriculture, Europe really does look like a fortress.

None of the tariffs are simple. There are different rates on a carcass and on butchered meat, and different rates on different cuts.

Under World Trade Organisation rules Scottish producers could see costs rocket to access European markets

For beef, the default tariffs registered with the World Trade Organisation by the European Union start just south of 60% tariffs and can go over 100%, according to Quality Meat Scotland.

For lamb, which in Scotland depends on the premium French market, the tariff can be 63% for boneless meat and 45% with the bone in.

If you think that is impossibly unfair on British farmers after Brexit, remember that this is the regime that has protected them for four decades from efficient, lower-cost US, Australian or Argentinean producers, sometimes with lower regulatory standards allowing for that efficiency.

Eye-watering

Countries that have struck trading deals with the European Union have carved out tariff-free quotas, or preferential tariffs, or both.

The UK starts a no-deal Brexit with the same WTO tariffs that the EU has had. Eventually, the UK could seek to carve out its own deal, though from a relatively weak negotiating position. Until then, the WTO tariffs look eye-watering.

Fergus Ewing said lower tariffs risked harming producers

Or it could display its credentials as a champion of free trade by slashing or removing tariffs.

That would have the added and important benefit of taking the pressure off price inflation in the early stages of life outside the EU. The sudden imposition of tariffs pours fuel on to inflationary pressures.

So here's where Mr Ewing gets involved, writing a letter to Michael Gove, the Brexiteer cabinet minister responsible for agriculture in Whitehall.

The Holyrood minister's letter recognises that, as things stand, a no-deal Brexit will leave Scotland's meat exporters facing these tariffs. It references the possibility of lowered tariffs for imports into the UK.

Stuffed

But the WTO rules state that if Britain offers such a deal unilaterally to one country or trading bloc, then it must do so to all.

So those efficient producers in the Americas and Down Under could sell their beef and lamb and pork to the UK under the same attractive deal being given to the EU.

At that point, much of Britain's livestock farming is served up with stuffing.

The WTO sets the most basic rules for world trade

So there's a balance to be struck; keep inflation under control, but don't undermine farming.

"While lowering tariffs in this way could mitigate the effect on consumers, by opening the floodgates, it risks considerable harm to our domestic producers," Mr Ewing wrote to Mr Gove. "It also gives away much of the negotiating capital for the future trade agreements which you prize."

So to the Holyrood minister, it requires "sensible and sensitive" application of new trade tariff powers, and preferably the introduction of Tariff Rate Quotas - limited amounts of imported produce, at lower or no tariff rates.

Chaos

For Scotland, without the pressure points of Channel ports, or the super-efficient cross-Channel supply chains of England's car factories, the food and drink sector looks to be the part of the economy that is most vulnerable to a chaotic Brexit.

There are those tariffs on the big export areas of beef and lamb. Fresh food delivery, of shellfish, for instance, risks being stuck at ferry port bottlenecks.

The scale of the risk was set out this week by a broad range of industry voices; the Food and Drink Federation of producers, Scottish Bakers, salmon farmers, the National Farmers Union Scotland, Quality Meat Scotland and the promotions body Food and Drink Scotland.

Together, they reckon they're worth £14bn per year to the Scottish economy.

But "even using the UK government's own projections, we estimate the cost of no-deal to our industry would be at least £2bn in lost sales annually. That is on top of the short-term chaos resulting from transport delays and labour shortages".

Haggis flavour

I encountered one source of that sales loss on Wednesday, reporting for TV from the Food and Drink Hub in Cumbernauld - a company that, for only five years, has been wholesaling produce from companies too small to have their own widespread distribution networks.

The Food and Drink Hub handles that for them. That's how there is such a range of Scottish craft beers and artisanal gins available across retail. It provides ScotRail with the contents of its snack trolley, including the haggis-flavoured Mackie's crisps.

Morrison's works alongside the Food and Drink Hub to provide much of the supermarket chain's local produce, with which it seeks to differentiate itself.

It likes how the Scottish business works so much that Morrison's has asked the wholesaler to operate a similar scheme with small local producers in parts of England, starting in Leeds.

For these small brewers, distillers, the bakers and purveyors of edible gifts, there is a big prize to be seized if the Food and Drink Hub implements its plan to get into exports.

But while Brexit provides such uncertainty, that plan is gathering dust. The potential will go unrealised until the Brexit mists clear, and that's not expected for at least a year. Probably much longer.

Pantomime

Such investment postponed is one of the glaring results of uncertainty for business across the sectors. Its lobby groups are bristling with frustration that the Brexit debate has left them no clearer about the outcome.

Enough of the pantomime, said one - the time for theatre is over. No more games - work together and sort it out, was the consensus on Tuesday night into Wednesday.

Currency markets have priced in an assumption that the scale of the government's defeat for Theresa May's withdrawal agreement deal has made a softer Brexit more likely. Sterling strengthened a tad on that basis.

Currency traders, however, know as much about this as anyone else. Their pricing of sterling is a gamble on a more economy-friendly outcome.

And in current circumstances, it's particularly risky to set odds on the outcome of politicians acting rationally.