Therexit: The economic fallout

- Published

The markets have not been moved much by Theresa May's tears, because they don't see her resignation changing much, or reducing the levels of uncertainty around Brexit.

A rift has opened up between Tories and former friends in business. Business lobbies are calling ever more forcefully for Westminster to sort out Brexit while avoiding a 'no deal' departure.

The report card on the May premiership has some changes to economic policy, but her fall opens the way for a bigger change, on the Conservative approach to immigration.

When a corporate chief executive quits, it's sometimes worth a look at the share price. A sharp rise suggests that the boss was holding back the company, and an exit was overdue: a fall indicates that investors saw the boss's presence as an important part of its future.

So how did the market react to Theresa May's announcement? By doing nothing much. The pound weakened 0.25% against the US dollar. The FTSE250 edged up.

That is partly because investors had already priced in her departure. They could see she wasn't going to cut a deal that got the government through Brexit, so assumed she would be resigning before long.

And with her gone, they can also see - as we all can - that there's little alternative route out of the political impasse under any other Conservative prime minister.

Meanwhile, there are other factors at play in the markets which give a better explanation of recent fluctuations, including the ramping up of a trans-Pacific trade war between the US and China.

Treated as dispensable

Just ahead of the announcement, the latest retail figures were issued by the Office for National Statistics, showing the volume of goods sold up by 5.2% year on year. The value was flat, after a very strong first quarter.

Add to that an unemployment rate at a 44-year low, and employment at record levels, and you can see the economic record while Theresa May was in Downing Street wasn't so bad at all. If she had focused on that, there might have been a less tearful conclusion to her time in office.

But the economy was never, personally, her main interest or strong point. It was a factor within the overarching determination to push through Brexit, but it was treated as if it were dispensable or an after-thought. For some, it could be compromised in the endeavour to placate those who saw the return of sovereignty as being of more value than the diminished growth rate which most economists reckon would follow.

The prime minister visited the Portmeiron factory in Stoke-on-Trent in January

In the turmoil within her cabinet, it was left to the minority of ministers with economic portfolios to remind colleagues of the potential damage to businesses and the economy. Phillip Hammond, as chancellor of the exchequer, and Greg Clark as business secretary, often cut lonely figures in making that case.

Under May's leadership, a gulf opened up between the Conservatives and big business, which has been causing alarm to both sides of that relationship.

Business lobbies have become increasingly frustrated that the internal Conservative debate about Brexit has been carried on with little reference to their warnings, which have been particularly strong about the potential damage of "no deal".

When the CBI director-general visited Edinburgh recently, for a lunch with members, the guest speaker was due to be Labour shadow chancellor John McDonnell.

He didn't make it to the Scottish capital due to the (doomed) Brexit talks with the government. But the invitation was a sign that the business lobby is turning its attention (with quite a lot of alarm) to the prospect of Jeremy Corbyn and Labour taking power.

'Nothing has changed'

The common message to all those reacting to the Therexit of Mrs May is that it doesn't change the arithmetic or provide a solution. Indeed, it prolongs the uncertainty, and introduces the risk of a harder-line Brexiteer pushing for departure without a deal.

The Institute of Directors, with a gently mocking tone, repeats the prime minister's words when she had a botched double launch of her long term care policy during that disastrous election campaign in 2017.

"Nothing has changed," says the IoD boss. "At least not much. A new leader will be faced with the same political challenges and the same economic realities. No deal remains a significant and growing concern for businesses and that cannot be wished away, whoever is in power.

"When companies and the country need serious, considered decision-making, we have pantomime instead."

According to Carolyn Fairbairn, director-general of the CBI, Theresa May "leaves office with the respect of business".

"But her resignation must be now be a catalyst for change," she added. "There can be no plan for Britain without a plan for Brexit.

Theresa May addressed the CBI conference in London in November

"Winner takes all politics is not working. Jobs and livelihoods are at stake. Business and the country need honesty. Nation must be put ahead of party, prosperity ahead of politics. Compromise and consensus must re-find their voice in Parliament".

A similar message came from Liz Cameron at the Scottish Chambers of Commerce: "We now urge political leaders to put country before personal ambitions, to ensure focus remains on solving the Brexit riddle.

"Westminster has already squandered far too much time going around in circles. They must realise that lack of direction has real-world economic consequences, causing the collapse of business confidence, which has a deleterious impact on investments and jobs."

Trade war

Some changes to economic policy under Theresa May's premiership are worth noting. She pulled back on George Osborne's focus on the Northern Powerhouse in the north of England. An industrial policy was being developed.

The government dolloped money into growth sectors where it saw strategic interest. But this was submerged by the battle to protect sectors, such as car-making and steel, that are particularly vulnerable to Brexit disruption. And in recent weeks, the need to open trade out beyond the European Union tripped up over the Pacific trade war.

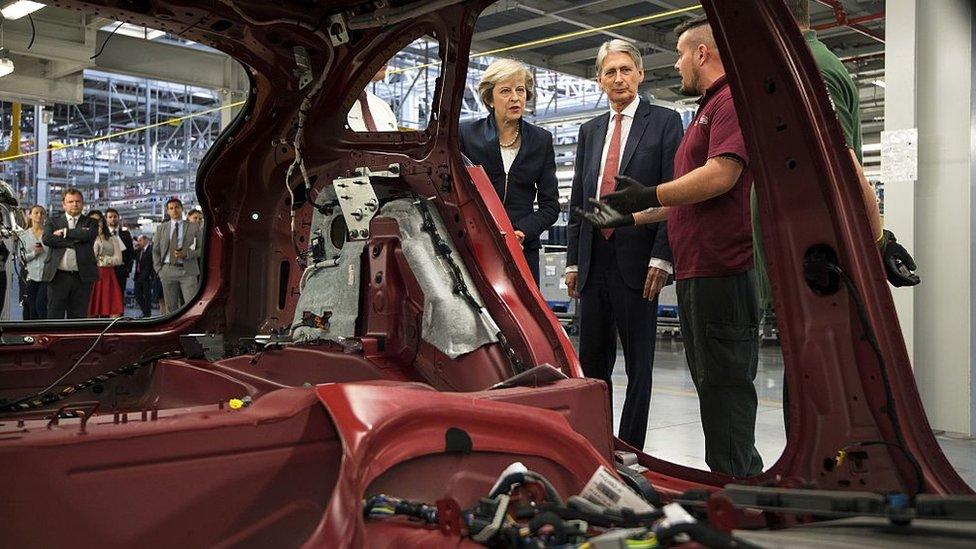

A visit to the Jaguar Land Rover factory in Solihull with Chancellor Philip Hammond in 2016

The Downing Street cabinet was split between welcoming Chinese telecoms technology (the prime minister's preference), and supporting the American case that Huawei carries too much potential as spyware. Being a much smaller trading power than the EU, and with trade deals to be done, expect more similar dilemmas.

As chancellor, Phillip Hammond dialled back on the austerity rhetoric, and pushed back his predecessor's target date for reaching a surplus.

While the Whitehall welfare budget continued to see big cuts, the biggest of them through the freeze on working-age benefits, the flow of funds to the National Health Service was increased.

Windrush fiasco

And what of the future? Apart from the dominant question of Brexit, and how to make it happen, the next Conservative leader will have the opportunity to re-shuffle the cabinet, putting different people into the economic ministries, and shifting economic policy.

My hunch is that there won't be enormous change, because there isn't the time, government headspace or political capital to do much beyond Brexit.

But one factor to watch is immigration. Theresa May has had a stranglehold on immigration policy for nine years since she became home secretary. It was on that that she placed her reputation for toughness. She gave us the policy of making a "hostile environment" for those facing deportation, meanwhile blundering into the Windrush fiasco, of excluding long-time residents of the UK who had been invited 60 years ago from the Caribbean to fill labour market gaps.

Mrs May's cabinet included potential leadership contenders Jeremy Hunt, Philip Hammond and Sajid Javid

Mrs May shut out new thinking about how to handle immigration. Behind the Leave majority, it played a significant part. Even for the six years before that vote, her response to public opinion about it was to set an unrealistic target for reducing net migration to below 100,000 and then to stick to it, while deaf to unintended consequences - for instance, on overseas student recruitment.

The rest of the cabinet has sometimes been infuriated by Mrs May's intransigence on this when she was home secretary. Now in that role, Sajid Javid doesn't much care for the sub-100,000 target. In launching a consultation on post-Brexit immigration, he quietly dropped it.

That consultation features the question of what salary level should be set for an EU or non-EU national to get a work permit in Britain. The proposed level is £30,000, which business groups say is far too high to recruit the skilled staff they need in more junior roles.

The next Tory leader and prime minister is likely to want to take a more flexible approach than Theresa May. In Scotland, such a change would be welcomed across Holyrood's political spectrum, and by business lobbies.