Turbulence in economy class

- Published

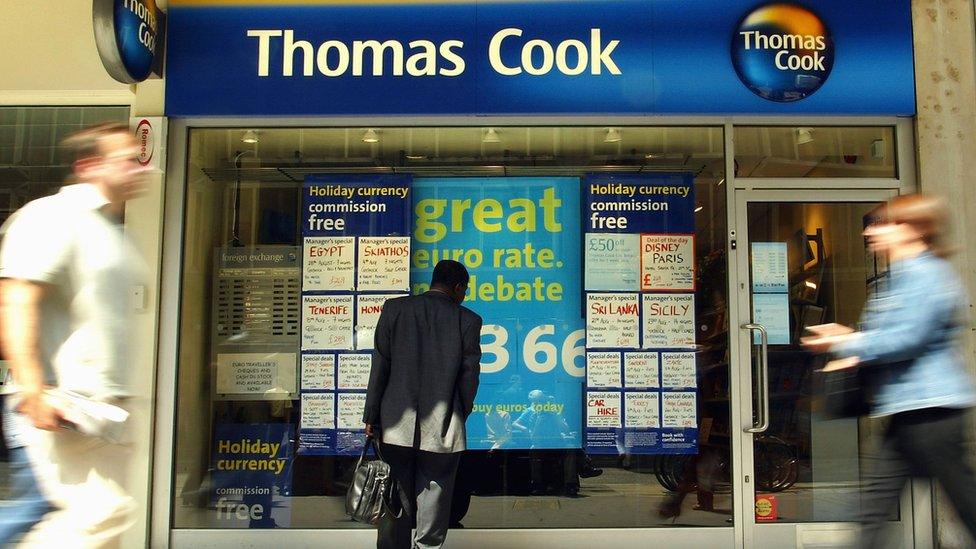

The operator's collapse cost thousands of workers worldwide their jobs

The demise of Thomas Cook has brought criticism of bosses and rival firms, and concern for its workers. The concerns may not stack as they seem.

The departure of such a big player opens up opportunities for others. They'll require skilled travel industry workers.

It would be a small irony if, amid unprecedented political turbulence and incompetence, the UK government successfully repatriated 150,000 holiday-makers from the collapsed Thomas Cook travel firm, and without too much hassle.

We're much more attuned to fiasco. And there's plenty that can go wrong in hiring a fleet of planes from scratch, and transporting up to 17,000 people per day. If Chris Grayling were still transport secretary, what would the chances be of him contracting an airline without any planes?

Day one, and the joint effort with the travel industry had 95% of those who had been scheduled to come home actually doing so - even though some were landing at the wrong airport.

Signs of that apparent initial success for Project Matterhorn quickly turned attention to the loss of 9,000 jobs in Britain, and more than that again overseas, whose work depended on Thomas Cook custom.

It turned also to the cost for flight-only passengers of finding a ticket that could get them home, finding that prices were soaring. They can keep rising even as they search and decide.

Passengers have faced queues and disruption, from destinations such as Majorca

And of course, it turned to the pay and bonuses of senior executives while the travel company traversed turbulent times and eventually crashed.

Well, here are a few thoughts, many of them contrarian in nature. You'd expect little else, right?

Long-term incentives

On that executive pay, £8m in pay and bonuses for the chief executive over the past five years looks like the going rate for a company of this size.

You might say the "going rate" is obscene. And compared with pay for cabin crew and others working unsociable hours, in cramped unhealthy aluminium tubes, and putting up with the rudeness of tanked-up British holiday-makers, then you'd have a point.

It's neither my role nor inclination to defend executive pay, least of all in a company that's gone under.

But much of these bonuses are usually paid in shares, which executives are, usually, not allowed to cash in for several years after they've been "earned". These long-term incentive plans are intended to encourage bosses to think, well, long-term.

So if these millions in bonuses were tied up in Thomas Cook shares, then they're worthless now.

Surges and spikes to flight prices

On profiteering rivals, anyone who books an airline ticket online these days expects to find search engine software that digs out the lowest price and offers a wide range of choice.

That has worked pretty well for the customer. If you don't believe me, book a British rail ticket now: compare and contrast.

Employees have been left without jobs

It's that same software that is causing prices to soar. Surge pricing is a feature of airline, hotel and Uber booking. If demand surges and supply falls, the algorithm kicks in and prices can go berserk.

There may be means by which the algorithms' inflationary effect can be capped.

But according to Skyscanner, the Edinburgh air ticket search company that knows a thing or two about this end of the industry, such spikes tend to be short lived. Prices quickly adjust back down.

Yes, they'll probably be higher than they were. But if a large chunk of capacity has just been taken out of the air, by an airline going bust, then the laws of supply and demand mean you'll be paying at least some more.

Headwinds from outside influences

And that brings us to the opportunity that comes form Thomas Cook's collapse. It's clear that it had failed to adjust to changes in its marketplace, not least the move to online booking, and to personalised itineraries, with declining demand for conventional package holidays.

One of its rivals, Tui, claims to have hedged against that, and against currency fluctuations that did so much damage to Thomas Cook, by vertically integrating.

That is, it owns many of the hotels and cruise ships, rather than contracting with foreign-owned providers.

Other airlines will fill the gap left by Thomas Cook

It still has to staff and fuel them in foreign currencies, and it faces headwinds from the Boeing 737 Max grounding and from Brexit uncertainty. But in a statement to reassure investors on Tuesday, Tui was keen to distance itself from the Thomas Cook way of doing things.

Its share price rose. So did the market valuation of Jet2, Ryanair, and IAG, owner of British Airways. Why? Because of that opportunity. Thomas Cook's failure does not mean the British have stopped wanting to go on foreign holidays.

Not only were 150,000 Thomas Cook customers overseas when the company went bust, but a million or so more were booked for future holidays. And while they may have lost deposits and worse, these people still want a holiday to look forward to. Many more will book closer to the next holiday season.

A dedicated workforce

So the airlines and other travel companies that can grab market share have a big opportunity. You can safely bet they're hard at work on exploiting it.

For airlines, the rebound may be subdued. For the past couple of years, there has been over-capacity in the lower-cost segment of the European market. The departure of Thomas Cook relieves some of the pressure on Ryanair and its ilk.

For those successful in grabbing market share in this people-intensive industry, they will need to recruit skilled travel industry workers, from cabin crew to booking agents to foreign hoteliers.

The Thomas Cook shop on Gordon Street, Glasgow, was in darkness on Monday morning

It's clearly very tough to lose one's job. And the evidence we're seeing is that Thomas Cook had a dedicated workforce, who deserved better.

But in a tight labour market, there are much worse circumstances in which to be forced into the search for a new job.

Nimble, innovative and lucky

Not every sector can be so confident. While some see the demise of Thomas Cook as a victim of Brexit, others see it as an early sign of the corporate clear-out that comes with an economic downturn.

If so, others will follow in other sectors. The harsh, sometimes brutal Darwinism of the marketplace will take the weak, goes the orthodoxy. It will clear space for growth of the more nimble, innovative and lucky.

It may also re-shape the job market for those whose skills are aligned and adaptable to the future demands of fast-changing technology.

- Published23 September 2019

- Published23 September 2019

- Published22 September 2019