A new monster from the deep

- Published

This photo of the Johan Sverdrup oil field was taken from a helicopter as people wait to land at the North Sea oil field

A vast new oil field in the North Sea has come on stream, drawing on new technology for greater efficiency and far greater profits.

Its estimated benefit to the government over five decades is estimated at £80 billion. The Norwegian government, that is.

So why has Norway done so much better out of North Sea oil? Some luck, some choices, keeping work in-country - above all, being an investor as well as levying tax.

The Kraken awoke. Mariner is heavy, but making headway. Clair Ridge is full of gas, and no relation to Sophie, the political interviewer.

They are all very large oil and gas fields in the North Sea, which drove the investment boom at the start of this decade, and now represent a large share of Britain's hydrocarbon output, as older fields rapidly deplete.

But less than 20km (12 miles) across the sea boundary and 90km (56 miles) west of Stavanger, Johan Sverdrup is the daddy of the new North Sea.

He was the man who fathered modern Norwegian parliamentary government in the 1880s. More recently, after its discovery in 2010, his name was given to a humongous offshore oil field.

Johan Sverdrup, a Norweigan prime minister, whose name was given to the new oil field

On 5 October, it began production. It's hard to overstate the bonanza it has brought to Norway's industry and finances, and it's being presented by Equinor, its operator, as a model of how to do offshore energy in the 21st century.

It all makes for quite a contrast with Britain, where world-leading cultural institutions, the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre, were this week ending sponsorship from oil companies BP and Shell.

We're in a period of tension between the amazing achievements of offshore engineers to unlock access to fossil fuels on which we continue to depend, at the same time as pushing for an end to that dependence and a shunning of the oil majors.

Footprint

The numbers for Johan Sverdrup are colossal. At peak production of 660,000 barrels per day, it will build up to a third of Norway's output. The field contains 2.7 billion barrels.

The cost of developing it was £7.5bn (US$9.2bn), and getting to first oil has taken only four years from approving the project.

It has come on stream two months ahead of schedule. And being developed during a downturn for the industry, it successfully stripped out nearly a third of the anticipated costs.

A few factors that are particularly noteworthy:

The project has stripped out the huge carbon footprint involved in extracting hydrocarbons. Instead of requiring generators offshore, the platforms are linked to the Norwegian grid by a 62km (39 miles)cable.

Although the cost of developing it has been colossal, it breaks even at an oil price of $20 per barrel (Brent crude is currently trading just below $60). And when you look only at the production cost, once production has plateaued, it will be below $2 per barrel.

The economic benefit of all those development projects has been strongly focussed in Norway. Some 70% of contracts have gone to companies with an address in the country. While saying they are winning contracts amid tough international competition, even with Norway's high labour costs, it has an uncanny knack of keeping contracts in-country. (By contrast, note the recent announcement that Equinor, in a joint venture with Perth-based SSE in the vast Dogger Bank wind farm, is sourcing its turbines from a GE factory in France.)

In the 10 years to take the oil field to full production, the development of the field will have involved 150,000 person-years of work. By using technologies, which were not available when older fields were being developed, it has removed the need for two million hours of offshore work.

Earnings from Johan Sverdrup over five decades of anticipated lifespan, are estimated at £125bn. Of that, in addition to all those jobs, Norway is looking at a gain of £80bn in tax and profit.

Major investor

The comparison with the benefit to the UK from recent oil developments is stark. Offshore oil and gas taxation has risen above £1bn per year, but it is not expected to rise much more in the current market and with current profits.

Extraction of oil and gas from mature UK fields is getting more expensive and therefore less profitable. Developing deep sea fields west of Shetland, along with technical challenges around high pressure and high temperature, has meant the Treasury to provide bigger tax incentives.

Norway has built up a vast oil fund, from which it draws a modest amount in earnings each year. To do so, it has foregone the lower tax that other oil producers, including the UK, have handed to their populace.

Compared with Britain, it has been lucky in tax revenue terms, in that fields have been larger and typically more profitable. Over the four decades of production, the UK's oil and gas profile has tended towards maximum output at times when prices and profits have been low. Not so in Norway.

But the big difference is that the Norwegian state has been a major investor. The UK government was, until the Thatcher government sold its stakes.

Some of Oslo's investment has been through its 67% stake in Equinor, known until last year as Statoil. That company owns 43% of Johan Sverdrup, as well as operating it.

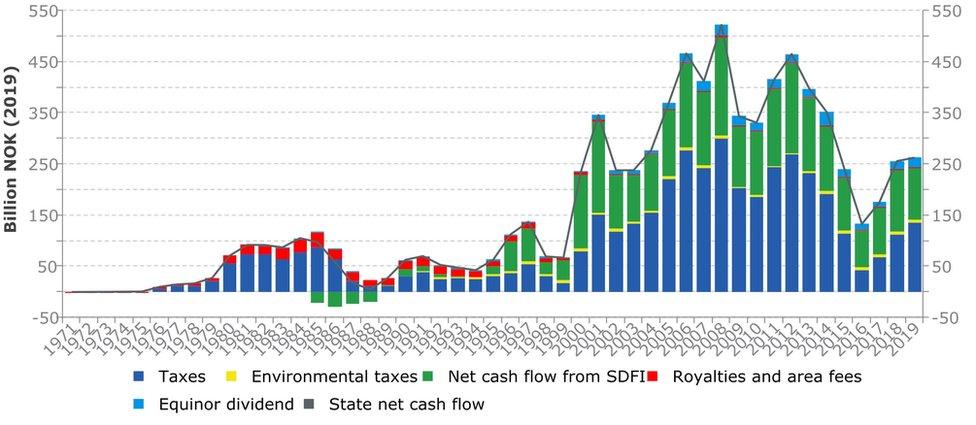

Net government cash flows from petroleum activities 1971-2019

(SDFI: state's direct financial interest)

The field was discovered in 2010, with the first successful drill by Lundin Petroleum, a third of which is owned by a Swedish-Canadian family, based in Geneva. Equinor is the second biggest shareholder.

Petoro has a 17% stake. It is the company that manages the Norwegian government's direct stake in 34 producing fields, with licences for a third of Norway's oil and gas reserves. Last year, it paid £10.6bn into the Norwegian state oil fund.

The Oslo government's stake in Equinor brought in £1.3bn in dividends to the government, there was a £600m revenue from environmental tax, and the main tax on offshore oil and gas brought a further £10bn. The budget for this year is for more of the same.

With Johan Sverdrup now onstream, that flow of kroners is set to stay strong for years to come.

- Published4 October 2019

- Published2 October 2019

- Published8 January 2019