A financial history of Edinburgh and the key players

- Published

A new book tells the story of the rise and fall of finance in Scotland, from a position of weakness in 1695 to the crash of 2008

Raising capital helped expand Edinburgh and innovation included bank notes to overdrafts to the first municipal fire services

Much of the story is about finance as an assertion of national identity and autonomy but the book's author notes that the decline of banking In Scotland has put it in a role similar to that in England's northern cities

I was at Adam Smith's house the other day - a fine pile squeezed onto a small piece of land between Edinburgh's Canongate and Calton Hill.

Panmure House had fallen into disrepair. Bought in the 1950s by the then new owner of The Scotsman, Roy Thomson, he gifted it for community use, and it took a fair battering as a youth centre.

Heriot-Watt University has spent about £6m on knocking it back into shape, creating what it calls "a hothouse of economic and social debate". It gives the Scottish capital something more than the nearby Adam Smith gravestone to show off to visitors who wish to pay homage to the father of economics.

The occasion was a gathering of economics students. I was one of the speakers, talking about the mass communication of economics' sometimes abstract, complex and oft-misunderstood concepts.

I asked the students about the financial crash. Did they know how one Robert Peston became a household name back then? Answer came there none.

The demise of Halifax Bank of Scotland and the rescue of Royal Bank of Scotland was going on while they were in primary school. This seismic change barely registered, and is now part of economic history.

Years of famine

As I've written before, those who fear that we're condemned to make the same mistakes again, unless we learn from history, have set up the Library of Mistakes in an Edinburgh New Town mews.

For everyone else, there's Ray Perman's new book: the Rise and Fall of the City of Money: a financial history of Edinburgh.

He's taking the long view, from 1695 and the founding of the Bank of Scotland, only months after the Bank of England.

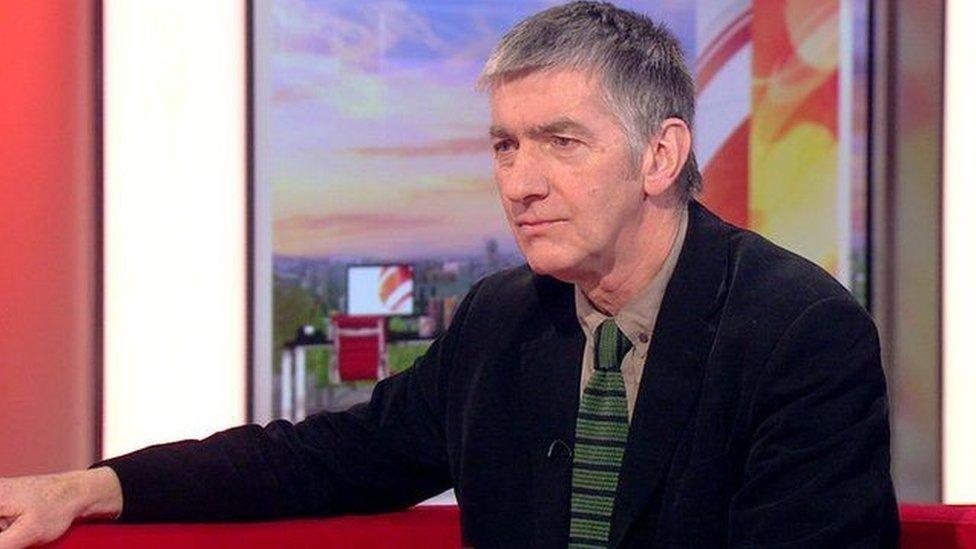

This former Financial Times journalist brings it up to date with his superb understanding of Scotland's modern finance sector, and the key players in recent decades, having been first chief executive of Scottish Financial Enterprise.

Ray Perman is a former Financial Times journalist and was the first chief executive of Scottish Financial Enterprise

I interviewed him for Good Morning Scotland, and he observed that the bank crisis, as well as other commercial forces, have left Edinburgh a pale shadow of where it was even 20 years ago.

Not only has Bank of Scotland been submerged by Lloyds Banking Group and Royal Bank of Scotland, it is almost entirely controlled by decisions made in London: the nine life assurance firms he recalls from 20 years ago have gone, and only asset management remains a relative strength.

In the banking firmament, he observes, Scotland is of similar significance to Manchester or Leeds.

His book reflects the rise in the late 1600s, from a position of great national weakness. The Darien Scheme, the disastrous attempt to set up a colony in modern-day Panama, had blown a hole in the Scottish economy, as so many rich people had sunk investment into it.

Several years of famine had seen gold and silver head south. Scotland was not well placed to trade its way out of a capital shortage. Something was needed, and the answer was the paper bank note.

Slave trade

By issuing a "promise to pay the bearer", Bank of Scotland and Bank of England didn't have to carry all the gold and silver necessary to back the money they'd issued - so long as there wasn't a rush to cash in the paper for precious metal.

Royal Bank of Scotland came along in 1727, and the two rivals engaged in corporate sabotage to use this cashing of paper to put each other out of business. Conceding this wasn't going to work, they instead formed a cartel, and went after the common enemy: Glasgow.

Glasgow's merchants were setting up their own banks, much of it to finance their trade with the Americas - in tobacco, cotton, and as historians have recently taught us, they were deeply implicated in the slave trade.

Edinburgh banks tried the same trick on Glasgow banks, such as the Ship Bank, of cashing in notes. Glasgow fought back by counting out its gold and silver in the smallest possible denominations, at the slowest possible speed.

That may have been one reason they closed early: if you couldn't count out hundreds of pounds in pennies and farthings by closing time, the customer could come back the next day and the process would start again.

But the early closing (which I recall from my early days as a customer) originally had more to do with forgery and the Scottish winter. Bank tellers worked by candlelight through the winter months, so it was deemed too easy to pass off forged bank notes in the later afternoon.

Auld Reekie

The Edinburgh banks were dominated, at least in the boardrooms, by the aristocracy. The Dukes of Buccleuch had a sort of dynastic chairmanship. There quickly emerged a division, with educated, middle-class men (very few women feature in this story) actually making the banks work.

You can see, through this history, the extent to which banks became the brokerage between old inherited wealth and the new.

The new wealthy in Edinburgh were in search of a more agreeable lifestyle than cramped, dirty Auld Reekie.

Perman says the building of Edinburgh's New Town had a lot to do with power and politics

Perman chronicles the role of financial deal-making in making it possible to build North Bridge and drain the Nor' Loch, opening the way north to the building of the New Town. It had a lot to do with power and politics.

Savings banks grew out of the pioneering work of a minister in Dumfriesshire, starting up the Trustee Savings Bank. Scottish bankers invented the overdraft, and pioneered both fire and general insurance in the 18th Century, though they lost that lead to London.

Fire insurance companies sought to protect themselves and their customers with their own fire services in the cities. But they tended to be poorly resourced and, across different companies, they were poorly co-ordinated.

Huge conflagrations in the Old Town of Edinburgh exposed the weakness of that system, and the lord provost brokered an agreement with the insurance firms to set up the UK's first fire service.

In Glasgow, the police were in charge of the fire service when, on one holiday to mark the King's birthday, the firefighters had joined in the liquid celebrations. A factory fire began when a firework went astray, and when Glasgow's firefighters turned up, they were too drunk to do anything.

Canny and thrifty

A couple of large bank failures - the most notable being the City of Glasgow Bank, which led to a rare example of fraudulent bankers being jailed - led to a much more cautious approach to Edinburgh banking.

Scotland's reputation for canniness was not a prominent factor in the early days, when England still viewed its northern partner as lawless and a bit wild, with two Jacobite risings putting the Edinburgh banks in a significant position of power in finance for both sides.

By the mid-18th Century, buccaneers had given way to Presbyterian thrift and rectitude and Ray Perman's account of Edinburgh banking is running out of financial adventure stories to tell. Until about 25 years ago, it became rather dull, conservative and super-served by extensive branch networks.

But it spun out innovation in investment, much of it driven by Dundee's jute merchants. The City of Glasgow Bank failure had shown the risk of investing in too few overseas ventures, as American railroads enjoyed an investment boom. Not all the ventures were that secure.

Edinburgh's bankers learned they should steer well clear. In Dundee from 1873, Robert Fleming was figuring out that if you spread your risk across a wide range of investments, and place them in a trust, you've got a much safer prospect. His bank moved to London in 1909, and was bought by Chase Manhattan in 2000 for $7bn.

Alliance Trust is one remaining legacy from that era, still based in Dundee. But in recent years, it has been stripped of its active investment role. An activist investor targeted it, and new management outsourced its equity portfolio management.

Fintech future

Through the 325 years covered by Ray Perman's history, the financial sector has been an assertion of national identity, a source of some pride and a bulwark for the Scottish economy against being run from London.

Sir Walter Scott took a prominent role in fighting to ensure the Bank of England did not squeeze out Scottish banknotes, and thus it remains today (it's just that banknotes themselves are being squeezed out by digital transactions).

By the time Royal Bank of Scotland chief executive Fred Goodwin was pushing to buy Dutch giant ABN Amro, it was being encouraged with patriotic zeal by First Minister Alex Salmond. It turned out to be the most calamitous deal of all for Royal Bank of Scotland.

Ray Perman's book had reached the end of its narrative arc - both rise and fall. Or had it? The story of Edinburgh and Scottish finance goes on. The next chapter may be getting written in computer code, in the financial technology start-ups around Edinburgh University.