An intriguing investment comes amid the economic gloom

- Published

They may be smart, but are they any good as phones? A Chinese company is looking to Scottish tech skills to improve the quality of microphones

It arrives as the UK government finds yet more crisis funding for new technology firms

The Scottish government wants to see more flexibility in Downing Street's support for business

The old "dog 'n' bone" is back.

For decades use of the phone was in long-term decline but the lockdown has sparked a boon in, socially distant, conversations.

It's been a good few weeks for telecoms in general, as terabytes of data have kept us working and entertained.

Companies like Zoom have found a ready and eager new audience for its conference call software.

But the art of conversation relies on quality of sound.

And it's one of the curiosities of modern telephony that the thing that seems to work least reliably, or least clearly, is the speaking and listening bit.

Help may be on its way along with some good news for the Scottish technology sector.

A Chinese company, called AAC Technologies, has announced that Edinburgh is to be the site of its new research centre.

The firm is talking only six Scottish jobs to start with, but they might push that up to 20.

As with so many of the small tech operations, this one is tapping the ecosystem of skills in and orbiting around Edinburgh University.

That institution spun out Wolfson Microelectronics, a listed company bought over six years ago by Cirrus Logic. And now, AAC is recruiting from the pool of talent that worked at Wolfson, starting with the boss of the new Edinburgh centre, Colin Jenkins.

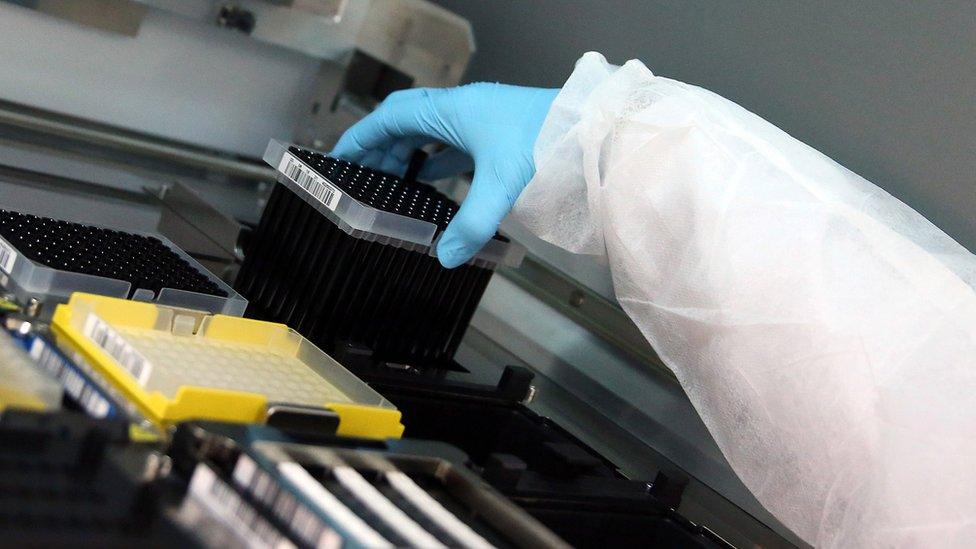

Their mission is to improve the Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) that function as microphones in a modern smart phone.

As explained to me by David Plekenpol, AAC's chief strategic officer, a smart phone now has five or six of these systems embedded in it.

Some do the conventional job of picking up sound, but more are busily tracking sound in order to deaden it, or to cancel out background noise with clever sound wave technology.

The applications are widespread.

A screen full of our friends or colleagues is becoming the new norm for those in self-isolation

The autonomous car of the near future will be loaded with such MEMS, as a means of interacting with the passengers, and as a way of controlling sound and soundproofing the interior.

The days of the computer keyboard may be numbered, at least in its current form, as voice controls become more common.

As a broadcaster, I am regularly astonished at the quality of sound that can be captured by a basic smart phone, sometimes when you're not even aware where the microphone can be found.

I asked Mr Plekenpol whether the phone experience will improve as a result of the effort AAC is putting into MEMS, which it then sells on to the major phone manufacturers.

"That's down to the consumer," he said.

It'll improve when phone users demand it. In recent, years, they have demanded ever improving functionality with cameras. If they make the same fuss about the quality of microphone, then the manufacturers will be sure to respond.

A tech-shaped future founded by crisis loans?

So why mention this now? For one thing, it's a pleasant and rare experience to be able to report on something positive happening in the economy of April 2020.

It's also because, amid the vast outpouring of borrowed government funds to get Britain through the Covid-19 crisis, something quite significant has happened.

AAC Technologies is too big and international to benefit directly, but that eco-system from which it now draws is getting a £1bn injection of rescue cash, in loans and grants, to address the needs of start-up firms in bio-science and technology.

Because they are often too far from the market to be able to turn to banks for funding, and because they are usually some way from making profit, the emergency government schemes to help business with grants and loan guarantees have not been reaching them.

So two elements have been announced by the UK government: one to back up larger tech firms which are already established in raising venture capital. Some £250m has been committed there, with £250m private sector matching funds ( though some sceptics think it should have achieved more private buy-in).

The focus on science and technology has been a hallmark of Boris Johnson's tenure as prime minister say industry observers

A further £750m is to help smaller firms: those already being backed by Innovate UK (as the name suggests, the government's innovation agency) and grants for those research-rich start-ups that haven't yet come within its orbit.

The obvious significance of this is that these companies are the seedbed for future growth and technology developments.

At least as significant is that the government is stepping up its use of risk funds in the sector, in tune with the rhetoric we've been hearing from the prime minister. If loans aren't paid back, they're to be convertible into equity.

Innovate UK has already established its role in this, in 13 years investing £2.5 billion, alongside private investors.

Although much of the Boris Johnson agenda - levelling up the regions of England, an infrastructure bonanza, and trade deals post-Brexit - could be blown off course by the health crisis, here is another part of what he wants to achieve, getting some funding that should have an impact long after the crisis is over.

There's widespread agreement on that. Those free market Conservatives who thought government has no role in backing and picking winners seem to be silent.

Questions over the current approach

But is it enough? The Scottish government's economy secretary, Fiona Hyslop, has broken with the co-operative vibes coming out of those Cobra meetings, to question the support Downing Street is offering business.

While there are criticisms of the way the Scottish government business grants are working, this Holyrood minister has concerns that the new scheme for technology start-ups may fail to work alongside Scotland's economic development agencies. They ought to know many of those firms better than Innovate UK.

She has written to the Chancellor, pushing also for more flexibility on the furlough scheme, to plug gaps in his offer made to the self-employed, and to "accelerate" the roll-out of loans to business - so far only reaching 12,000 companies.

Struggling firms could access money faster if the government guaranteed 100% of emergency loans, not just 80%, Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey has said

There is pressure on the Chancellor to increase the extent of government loan guarantees from 80% to 100%. This would remove banks' concern that their loan book could be impaired if those loans turn sour.

But Rishi Sunak has said he is not persuaded. In trying to save the economy from going over the Covid cliff, such rules keep moving, and the costs keep rising.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

WILL I GET PAID IF I SELF-ISOLATE? The rules on sick pay

- Published27 March 2020

- Published1 April 2020

- Published1 April 2020

- Published2 April 2020

- Published31 March 2020

- Published2 April 2020

- Published25 March 2020

- Published3 April 2020

- Published17 April 2020