Noteworthy: Clydesdale Bank's demise

- Published

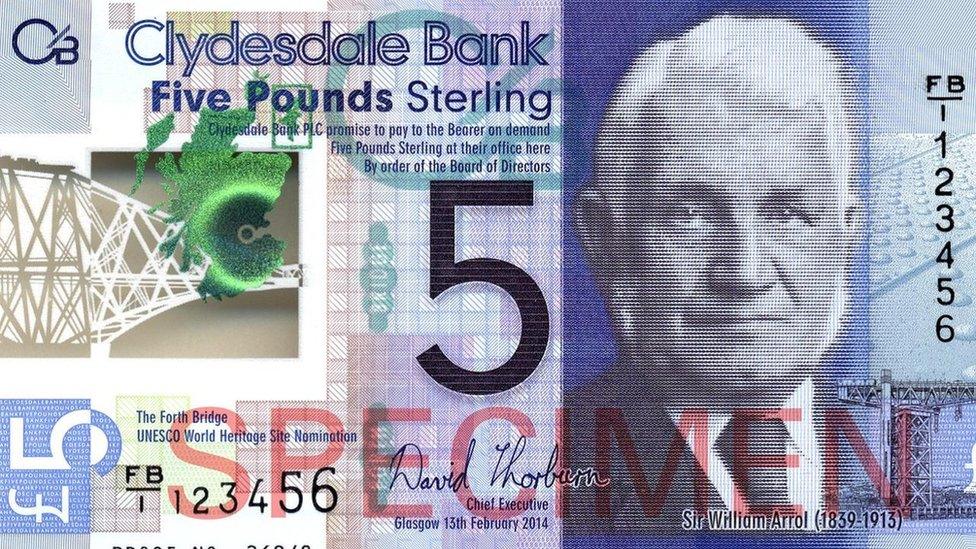

The Clydesdale £5 plastic note featured Scottish engineering pioneer Sir William Arrol

Clydesdale Bank is on the way out and although circulation of its banknotes will continue, that will be on a much reduced scale.

It harks back to the origins of paper banknotes, which Scottish bankers innovated, indulging in unscrupulous and sometimes farcical tactics to undermine each other.

If money seems scarce, Clydesdale Bank notes are about to become much more so. The brand's owner, Virgin Money, is retreating from its contracts to supply cash machines run by rival lenders.

No longer will you get a crisp Clydesdale polymer note when drawing cash out of Santander, TSB, Co-op or Asda machines. The contract to supply them is being taken over by the other issuers of notes, Royal Bank of Scotland and Bank of Scotland.

You might think this reflects the fast-declining use of cash. And that may be part of the story.

We're learning today of new Bristol University research for the Financial Conduct Authority showing a 19% reduction, or more than 10,000, in free-to-use cash machines in the two years to last March, while there was a 15% decline in the number of withdrawals.

The move to infection-free contactless card payments during the Covid crisis has accelerated the reduced use of readies.

But this has more to do with the even faster-declining use of the Clydesdale Bank brand, 182 years after its founding in Glasgow.

By the end of February, it will have disappeared from the fascia of all its branches, replaced by Virgin Money.

That bank, based in Edinburgh, was taken over by Clydesdale, or to be more accurate, its parent company listed on the stock market as CYBG. The 'Y' stands for its other legacy brand, Yorkshire Bank.

Retiring cash

In a reverse brand takeover, licensed from Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Group, CYBG last year renamed itself Virgin Money. Its plan is to use that to expand beyond Scotland and its Yorkshire turf as the leading challenger to the UK's dominant big five retail and business lenders.

This leaves a banknote anomaly - entirely appropriate, given that Scottish banknotes are themselves anomalous.

Clydesdale Bank, no longer a trading brand, will continue to appear on the notes you get out of Virgin Money cash machines, but not any others.

The idea of issuing a Virgin Money banknote must have appealed to Sir Richard Branson, particularly if his cheerful physog appeared on it with an airliner or balloon. But that's not happening.

The face of the Virgin founder Richard Branson will not appear on Scottish banks notes

Virgin Money is not saying how much cash it's retiring as notes are returned, but it will be a big reduction from the £2.3bn which I'm told is now in circulation - around 47% of the Scottish banknote total.

You wouldn't bet on it continuing indefinitely, because it's an odd and expensive advertising and marketing tool to support a brand being consigned to history.

Underlying pressure

That, after all, is what Scottish banknotes are - something with which to irritate London cabbies, and advertising for their issuers.

It wasn't always thus. Banknotes were an innovation in the early days of Scottish banking, when late 17th Century famine meant gold currency had to be spent on importing food. With gold therefore in very short supply, the banknote represented a promise to refund the holder who presented it with precious metal coinage.

As notes were issued in greater number than the gold and silver that backed them in the vaults, banks innovated in expanding credit. But they had to do so carefully. In the 18th Century, they were at risk of rival banks presenting them with a lot of notes at once, an unscrupulous tactic which sank some issuers.

The modern-day equivalent would be a run on a bank, when savers panic and demand to get their money out, far in excess of the funds available on the day. Remember the queues outside Northern Rock in 2007 - one of the first indications in Britain of the underlying pressures that led to the financial crash the following year?

The Scottish history of this is detailed in the recent magnificent history of Edinburgh (and Scottish) finance, City of Money, penned by Ray Perman.

He relates the dirty tricks visited by the Bank of Scotland, the 'Old Bank' on the Royal Bank of Scotland, 'the New Bank'.

But when two Glasgow rivals were founded, known as the Ship and the Arms banks reflecting the heraldry they used, the established Edinburgh rivals joined forces to see off the Weegie threat. It's a story worth repeating.

Paid in sixpences

Their threats and dirty tricks included successfully blocking the use of Glasgow notes to pay Customs and Excise. But Glasgow's tobacco merchants were loyal to their own.

In 1757, the Edinburgh banks were approached by one Archibald Trotter, a former trade financier, with a plan to undermine the Glasgow challengers.

On a salary of £150 and supplied with £5,000 in credit, Mr Trotter set up on Clydeside as a dealer in bills of exchange, intending to put the Glasgow banks under pressure with his demands for collateral coinage. The Glasgow bankers, writes Perman, quickly realised what he was up to, and the Arms Bank decided to have fun at his expense.

"They limited the hours when they were prepared to redeem notes, and paid him only in sixpences. There were 40 sixpences to the pound and Trotter was presenting £100 or more at a time, giving ample scope for error and delay.

"The bank teller would laboriously count out the tiny silver coins, occasionally losing count and having to begin again, or dropping one on the ground, providing another excuse for restarting the process anew, or finding one which might have been tampered with and having to go off to get a second opinion as to whether it was valid or not. If they ran out of time, the process had to be restarted the following day."

Banking hours were short, notes Perman, because counting coins by candlelight in winter was a risky business.

Mr Trotter's venture didn't last long. But from my experience, anyone who has spent any time more recently in an Indian bank branch probably knows how he felt.

- Published24 November 2020

- Published24 November 2020