Jenners: No appetite for old retail?

- Published

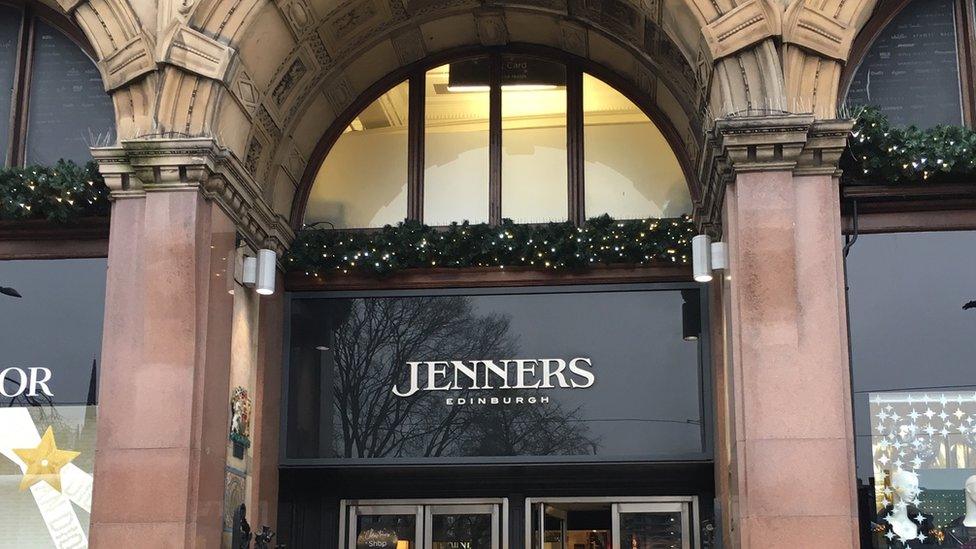

Jenners department store in Edinburgh has been at the site since 1838

Every city and town had a Victorian department store that captured the middle class spirit of lady shoppers - but in Edinburgh, Jenner's was a refined cut above

It is a big moment for the capital's city centre if its anchor store faces closure. That was announced by Frasers on the same day that two new online fashion giants expand into the UK's traditional retail brands

But the building's owner isn't giving up. The battle between commercial landlord and tenant is brutal, but where old retailers depart - at least on prime shopping streets - landlords are willing to invest in redevelopment.

For those of us who grew up in Edinburgh, Jenner's was an institution like few others, anywhere.

Into its extravagant sandstone facade had seeped generations of middle-class tradition along with the city's culture and social hierarchy. Pushing through its heavy doors opened into a sense of couthy capital quality, and permanence.

But its permanent closure has been announced, at least in its current incarnation, scheduled for early May, at a cost of 200 jobs. One of two surprises is that so few people are left, for so much floorspace: the other is that it may be saved, by an online retail billionaire.

There's a sort of irony in the reason for the closure announcement; the Jenner's operation is owned by Frasers, which is controlled by the man who has been most aggressive in salvaging bricks and mortar retail, Mike Ashley. He has failed to reach an agreement on rent with the building's owner, Anders Povlsen, the Dane who made his billions of kroner from online retailer Asos.

It is fitting also that the announcement came on the day that Asos has confirmed it is in talks to take over Top Shop, Top Man and Miss Selfridge from the wreckage of the collapsed Arcadia empire, while Boohoo, another rampantly successful online fashion retailer, is buying the Debenham's brand but not the stores.

Old retail has been cannibalising itself, but Mr Ashley seems to have run out of the appetite or the funds to continue devouring failed chains.

This is a moment in the transition, at which new, digital retail sees the appeal of having a real presence in a real shop, while getting a grip on older customer lists with older loyalties to older brands.

Carriage trade

But it's also a moment to get a wee bit nostalgic. Most cities and towns had a Victorian emporium of perfumery, stationery and leather goods, wigs, haberdashery and kitchenware. Some extended to victuals, comestibles and fine wines.

For many of us who remember the 20th Century, they are etched on the memory - early shopping experiences opening into a cathedral of retailing wonder, of stairs and passageways leading off into new possibilities.

I recall RW Forsyth's - very stiff and stuffy, it smelled of polish, and is now home to Top Shop. Patrick Thomson's on North Bridge was too small to last. At the west end of Princes Street, Binn's had the clock where teenagers met friends and (in my dreams) a date. More recently branded Frasers, it is currently being distilled and blended into a vast whisky visitor experience. Goldberg's was downmarket and breezily brash. All were Edinburgh institutions.

Edinburgh had numerous department stores

In the 1970s, John Lewis joined, the only part of the monstrous St James Centre building now remaining. Debenham's adapted a gentlemen's club soon after. Harvey Nichols brought pricey, metropolitan cool as a new century beckoned. These were imports from the south, as supply chains stretched, and so did Edinburgh's spending power.

In London, you could visit Harrod's or Selfridge's, but they were as much for tourists, and lacked much sense of their home city.

Jenner's was different. Its roots and its continuing success, while other department stores folded, were in its "carriage trade" - retail on one site, with a strong focus on service, and a safe, comfortable, familiar environment for the lady customer, where she could meet her friends.

The classical sculptures on its facade were put there to demonstrate that the business was literally supported by women. The current shop was opened in 1895, replacing a building that burned down, and featuring innovations such as electric light and lifts.

Retail theatre

When my grandmother moved from Glasgow to Edinburgh 41 years ago, at the age of 80, she stuck religiously to The Glasgow Herald but her arrival in the capital was secured and sealed each week over a genteel coffee in Jenner's with a friend, who happened also to be Ronnie Corbett's mother.

For some years, the toy shop was my main interest, down the stairs and into a cavern of seemingly boundless childhood indulgence. While Santa Claus might be suspiciously ubiquitous, this felt like the location one could be confident of finding the genuine article.

Some years on, working nearby and with no intention of buying, I would take a short cut to appreciate the atrium - a retail cathedral. Other department stores had chosen to fill in such spaces with more flooring, expecting more sales, but Jenner's stuck with the original design, recognising something that's now being taken more seriously - that shopping is about theatre, headroom and experience.

At Christmas, a tree would dominate its four storeys, cut from the Highland estate also owned by the Douglas-Miller family.

In the well of the atrium were men's clothes, because that target female customer passed through, and traditionally did the shopping for husbands and sons. In January, with the tree removed, the space was - until this year - given over to a cornucopia of sale items.

Elevated Flannels

What went wrong? The buying power of a single-family firm was waning, the internet was eating into sales, and the Douglas-Millers cashed in with a sale to House of Fraser.

That chain then ran it like its other stores; stripping it of its Edinburgh distinctiveness, centralising its stock control, turning ever more to concessions to fill the space. That had the attraction of greater efficiency, and better margins, but lacked long-term strategy.

House of Fraser, with roots in Glasgow but its ownership shifting to China, fell into administration and into the hands of Sports Direct and Mike Ashley.

Will Mike Ashley part with the Jenners brand?

Britain's department stores have struggled to find an answer to the internet. These original shopping malls, where you could find most things under one roof, have lost their way.

Mr Ashley seems in two minds; whether to apply his successful retailing strategy with Sports Direct, of branded sports gear piled high, sold cheapish: or going up-market in a strategy he calls "elevation" demonstrated by his new "Flannels" brand of fashion outlet.

While he has bought the Frasers store in Glasgow, much of his strategy so far has been to drive down rental costs in a ruthless battle with commercial landlords and hard bargaining over space for concessions. There have been previous reports, apparently fed by the feuding tenant and landlord, that Jenner's was to move elsewhere, or that its owner would clear it out and re-develop.

Wynd up

It's possible this latest announcement is another negotiating ploy. Or Mr Povlsen may have called the Ashley bluff.

The Dane - when he's not "re-wilding" his large estate in north-west Sutherland - knows a bit about retail, and his people seem to think that the building he bought in 2017 can be a successful shop without having the Jenner's brand. He may persuade Mike Ashley to part with the Jenner's brand, as his spokesman seems intent on keeping it open.

Legal & General, as owner of the building occupied by Debenham's, also on Edinburgh's Princes Street, has plans to redevelop it into multiple uses; a hotel in its upper storeys, a wynd of smaller shops and eateries through to Rose Street, a rooftop bar and basement gym. You can imagine the building becoming something similar, unless Mr Povlsen can find someone else to retain Jenner's current operations.

It's a reminder that even during tumultuous times for retail, and assuming that the current footprint is far bigger than the industry can sustain, many of these buildings will find new uses, and retail will develop into new forms.

It will also adapt to new social and environmental pressures. On a day when clicks and mortar crossed over each other - Asos talks on Top Shop, Boohoo taking over the Debenham's brand - Ikea made a big announcement. It's not scrapping its culture of low-cost, disposable, replaceable furniture and homeware, but at least it's slowing it down.

It is trying to find a business model for online ordering of replacement panels or worn out cushions to prolong product life. Customers have been telling the Swedish retail colossus they want to retain items for longer before they are replaced.

As you might do, for instance, with a venerable department store.

Related topics

- Published25 January 2021