Price inflation: The heat is on

- Published

Price inflation is already evident, from margarine to mince to used cars and petrol.

But it is rare to foresee how much higher it is going to get, as the cap is raised on household energy costs.

A sharp rise in price inflation has rarely, if ever, been so well-signalled. On 1 April, the price cap on household fuel goes up - a lot.

Today, we find out precisely how much.

A few days after that increase, employers and employees see a significant hike in National Insurance contributions, and council tax bills will surely rise - meaning less disposable income.

Price inflation has already been getting well out of its 2% target zone, most recently at 5.4% for year-on-year increases across a big basket of goods and services.

It is food and petrol where people have already noticed prices going up fastest, along with a 31% increase over the past year in the price of used car.

Petrol is up from £1.14 per litre at the end of 2020 and is now heading towards £1.50 on the back of crude oil prices around $90 per barrel.

That food increase is not for everything. Bread prices are stable, and flour is down on last year. Bananas are slightly cheaper, and avocados were 8% lower in December.

But for many of the staples, prices are sharply up: pork sausages by 9% according to the 2021 figures from the Office for National Statistics: mince by 5%, roasting beef by 29%, margarine by 31%, milk by 7%, a cauliflower by 20% and pears by 23%.

And away from food, the figures showed increases of 12 to 15% year-on-year in materials for DIY, household furniture, bicycles, garden and camping equipment, fiction books and stuff for babies. Many of our household appliances come from the European Union, and they're up by more, possibly because of the extra hassle in getting them across the Channel.

An iron is 21% more expensive than last year, says the ONS.

Predictable spike

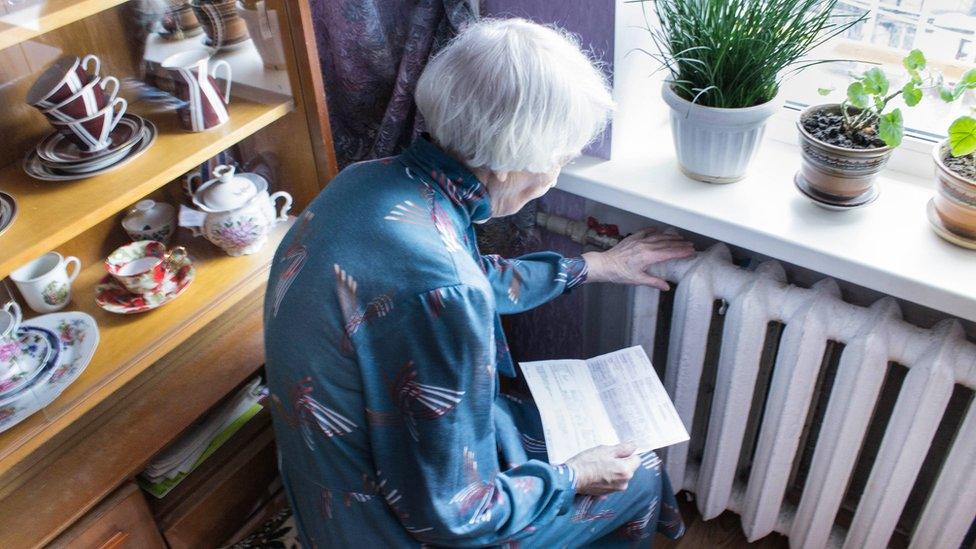

But it's energy that brings the most pain. Along with food, it's not a discretionary spend. So to have both those factors rising puts particular pressure on lower income households.

The wholesale cost of natural gas for delivery this winter has soared from below 50p a therm last summer, to highs of £3 in October and rising well above £4 in December.

This week, it is trading below £2, but that's still four times the cost that our bills are currently assuming. The cost will be passed on.

In bills between April and October last year, the typical gas-heated household was paying £373 on an annual basis, out of a total bill of £1,138.

The heat was on with the price cap rise last October, where that wholesale gas element went up to £528 out of £1,277 for the year.

But that was when the price spikes began, and they feed this April's increase. The regulator, Ofgem, is required to pass the average cost on, meaning a doubling of that wholesale element.

The rest of the bill is made up of the cost of the cables and wiring that gets power to your home, social and green levies to support low-income households and subsidise renewable power, plus administration costs and 5% VAT. A constrained level of profit is allowed, currently at £23 on the typical dual fuel bill.

That's what makes this inflation spike so predictable. We we already know months in advance the scale of the rise of one key element of household spending, and we can foresee the impact that has through the delay in the price control mechanism.

Through the roof

What we don't know is how long that will continue. The price of gas depends on global demand, and supply could be severely disrupted by war between Ukraine and Russia. European storage of gas is at record lows, and Britain has little storage.

We do know that the bills are yet to come in for rescuing millions of customers whose suppliers went bust. That came at a cost to the remaining suppliers, and they are expecting compensation with the next price cap rise, six months from now.

The other element we do not know is how people on tight household budgets are going to handle price rises on that scale - even after UK and Scottish governments have provided some mitigation measures.

Fuel poverty is alarmingly high in Scotland. That includes people who spend more than 10% of their disposable income on household energy, leaving insufficient for an acceptable standard of living.

That can be because of low income, or because of poorly insulated housing or health conditions which bring high heating requirements.

The most recent Scottish government statistics from 2019 show:

Nearly a quarter of homes were in that position, or 613,000 households.

One in eight homes, or 311,000, were living in extreme fuel poverty, meaning more than 20% of income was going on household fuel.

In the most remote rural areas, 43% of households were in fuel poverty.

Across all rural households, 19% were in extreme fuel poverty.

Fuel poverty was experienced by 37% of those in the social rented sector, and 20% of those in private housing, including renters.

Those heating homes with electricity were much more likely to be in fuel poverty than those using gas, by 43% to 22%, along with 28% of those using oil heating.

A watchdog that monitors actions to recover personal debt have noticed a rise already, reflecting widespread problems in retaining earnings through the pandemic. It is braced for a lot more.

There is a knock-on effect for businesses that depend on discretionary spend - life's unnecessary luxuries, from fashion to travel and eating out - when so much more money is going on the basics back at home.

Those poverty figures fluctuate widely from year to year, mainly because of the varying cost of fuel. And this year, we can expect fuel poverty, like too much wasted heat - will go through the roof.

Related topics

- Published3 February 2022

- Published23 January 2022