Energy bills: On the front line

- Published

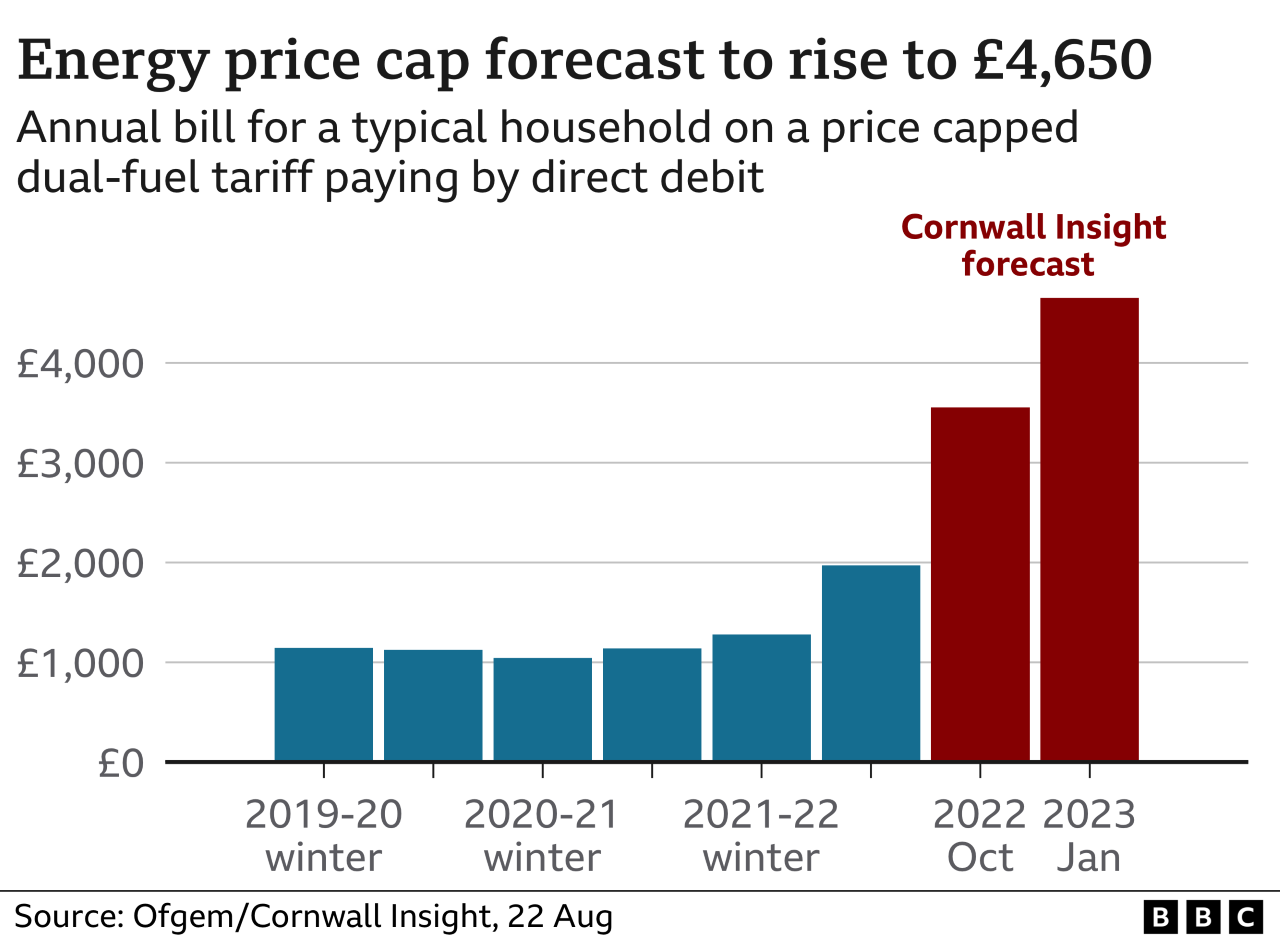

Fuel bills will hit £3,549 a year from October, without any decision yet from Downing Street about how to respond.

British consumers are not alone: the cost of energy is being manipulated from Moscow to exert political pressure across Europe.

Putting a cap on Britain's price cap has appeal, but there may be better ways, which take the opportunity to secure permanent change in energy use.

The missiles may not be flying near your neighbourhood, but be in no doubt that you're in the front line of war.

The munitions are delivered by your energy supplier, direct to your email inbox, or your front door mat, with an 80% rise in your household fuel bill from 1 October.

It's rising because markets say it should. That price cap protects you only from short-run volatility. It doesn't put off a reckoning with higher wholesale costs which have been met for the past six months by your supplier.

Resulting from the scramble to fill European reserves for next winter, wholesale prices have been back at record levels this week.

The manipulation of those markets from Moscow, by sharply reducing the gas supply, is a key strategic weapon of economic war.

The tactic is intended to weaken European and British resolve in support of Ukraine, by exploiting a perceived weakness of western politics.

The Russian view of neighbours to its west is that they are decadent, with a short political attention span, and far less resilient than Russia in sustaining hardship.

By turning the screw on the Nordstream pipeline, the primary route of Russian gas under the Baltic and into Germany, the Kremlin administration can watch prices rise. That piles pressure onto the political leaderships across Europe, as well as threatening to fracture the unity of the European Union.

Having eliminated opposition and media scrutiny, Vladimir Putin faces no such problems at home.

It's a huge gamble by Russia, because the European (and British) response is to find other sources of energy - turning back to nuclear and coal, building facilities for import of Liquified Natural Gas on tankers, while speeding up renewable power investment.

Whatever the outcome in Ukraine, it's very unlikely Europe could return to being so dependent on Russia.

So the long-term game for President Putin must be to build gas pipelines to Asia, selling to India and China instead of Europe, as he is already doing with cut-price oil.

If those new customers are wise, they will watch closely how Russia uses its clout as a supplier.

This is not the first time Moscow has used energy as a weapon, to coerce neighbours to its will and secure Russia's sphere of influence.

So until supplies can be secured from elsewhere, or vast quantities of fossil fuels are no longer required, what are Ukraine's European and British backers to do with this front in the energy war?

That's the challenge facing, among others, the Conservative government at Westminster. From 5 September, a new prime minister will have to respond to the biggest challenge since, well, Covid.

And the choice is whether the resilience and acceptance of financial hardship is one that is for households, businesses and charity to handle? Or is it as much a function of government to defend its people's economic security as its territorial integrity?

Within that are many other choices: among them, of how much to target support to those least able to handle inflated energy prices and wider inflation, or alternatively to make this a national endeavour in which everyone gets support.

How much will a Tory PM in 2022 rely on the market to ration energy, in a spirit of individualism, perhaps as a reaction against the extraordinary levels of state intrusion into homes and lives through the pandemic?

Germany is considering how to ration by other means, with the real possibility that it could simply have insufficient gas this coming winter to heat homes and fuel its factories.

Government officials are drawing up plans for how to allocate supplies to essential factories, recognising it will be impossible to turn off the heating taps for homes.

Thermostats for air conditioning are being turned up, and when autumn comes, they will be turned down. Lights are being dimmed: floodlighting and fountains turned off, while swimming pools or showers go unheated.

Rationing is a dimension to the crisis that the British have barely considered, but it will surely come.

According to the Economist magazine, evidence of what happens when prices rise, and when prices are capped, is not reassuring to governments who reach for state subsidies (it is editorially for markets and against most subsidy).

State of limbo

It argues price caps fail to lower energy use or to change behaviour towards other sources of energy. An American trial in lowering prices for low income households resulted in higher energy use.

Ukraine offers cash to households in most needs, it reports, preserving the link between bills and energy use, and therefore also the incentive to cut back.

A part of Austria offers subsidy on the first 80% of typical household use, while leaving the incentive to cut back on the remainder.

What about Britain? So far, it has a dual response: a blanket £400 per household to ease the pain, and a series of grants aimed at those on means-tested benefits, disability payments and the state pension.

That was a scheme devised by Rishi Sunak in May, when it seemed the price cap would rise from £1,971 per year for the typical home to about £2,800.

The scale of the increase - a typical household energy bill will now hit £3,549 a year - announced today to be applied from 1 October, is unlikely to surprise anyone applying Ofgem's formula to wholesale prices. But in a state of limbo, between prime ministers, waiting for today's formal announcement was used to buy time.

Not any longer. Downing Street now has to decide how it responds to the economic war footing being required here, as it is across Europe, and once decided, to do so swiftly.

Related topics

- Published26 August 2022

- Published26 January 2023