Liz's big bazooka or the Truss blunderbuss?

- Published

The Energy Price Guarantee could be about to save you thousands of pounds, while loading that on to debt. As a billpayer, you win: as future taxpayers, the kids lose.

Economists acknowledge it had become politically unavoidable as projections of future price increases reached dizzying heights of scariness. But they are scathing about its cost, poor targeting of those who most need help, and the removal of an incentive to cut back demand for energy.

Without a price cap, business already knows about soaring bills. It awaits clarity on what the new prime minister means for them to have "equivalent" support to households.

Your energy bills are going up in less than two weeks, by around a quarter. That's if you are on dual fuel gas and electricity, on a flexible tariff and if you haven't yet found ways to cut back on usage.

The rise from nearly £2,000 for a typical British home to a maximum of around £2,500 is what we're to call the Energy Price Guarantee. It replaces the energy price cap, introduced four years ago to stop energy firms charging rip-off rates for those who can't be bothered shopping around.

Now, no-one is shopping around. There isn't much choice. The only option now is to hunker down for a tough winter.

If you missed out on the announcement of the Energy Price Guarantee, it's probably because Liz Truss announced it minutes before it was also announced that the Queen required "medical supervision". She died a few hours later and the rest really has been history.

If you missed out on the detail of the Energy Price Guarantee, that's because there wasn't much to be had. The £2,500 level is a rough estimate, knocking £1,049 off the price Ofgem had set as a limit from 1 October. That's for the typical home, not for all homes - the cap is on the price per unit of gas or power.

Liz Truss was, you may recall, only two days into her Downing Street residency, having paid not much evident attention during the Conservative leadership campaign to the clamour for some clarity on what government was going to do.

In August, wholesale prices for gas were soaring to 15 times the steady level they were at before August 2021. In energy markets, there was a dash for gas, to secure contracts which could fill Europe's reserve tanks ahead of winter.

Because Germany and other countries were pulling back on gas use in summer that goal of having the tanks 80% full was achieved faster than expected. The traders pulled back on some scarily high prices.

Britain doesn't have much storage capacity beyond the original sub-sea oil and gas reservoirs, and while there are signs of less British demand for energy in recent months, it's due to a response to high prices rather than significant effort or exhortation by government.

So having reached dizzying heights of scariness, which fed through the Ofgem price cap formula to independent forecasts of price rises in January to more than £5,000 a year for the typical household, wholesale gas prices have fallen by more than half.

They're still more than six times the level we were used to, but for now, the really truly scary bit is over. And with an adjustment to an energy future which is not reliant on Russia, it's getting harder for the Kremlin and its state-controlled oil corporations to exert further price leverage over Europe and Britain.

Lower prices will be a relief for the Treasury, which wrote a blank cheque for Liz Truss's price guarantee. However high the wholesale prices, the government is going to pay the difference between the actual cost and that typical £2,500 bill. If it were to rise to £5,500, that would put the government on the hook for more than half the cost - borrowing £3,000 to pay the difference for that typical home.

Heavy pounding

Quite how it pays for this is yet to become clear, but we're assuming it will get added to Britain's already high pile of debt.

If things go badly with wholesale prices, the cost could be around £150bn. If wholesale prices stabilise, it might look more like £50bn.

The cost of servicing that extra debt, as interest rates rise, is becoming more of a burden, squeezing out expenditure on public services, and handing the bill to future taxpayers.

And while money markets are still willing to lend to Britain, the value of sterling against the US dollar suggests they are taking a dimming view of Britain's economic prospects. It may require higher interest rates if currency traders are to prop up the pound.

The high and uncertain cost is just one of the reasons why economist commentary on Liz Truss's 8 September announcement was less than flattering. Deemed at the time to be the defining moment for her premiership, the gist of it was that the support package had become politically unavoidable, but that this was not a good way of designing it.

Paul Johnson, at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said it was "deeply disappointing" that we had such a radical and expensive departure from the norm with not one hint of costing.

The government "needs to be immediately working out its exit strategy from this huge and costly intervention. It is concerning that it appears to be committing to this policy through next year as well as this.

He said: "It is perhaps forgivable not to be able to come up with something better designed and better targeted right now. Surely there should now be a concerted effort to come up with something better for next winter. Failure to do so would be enormously costly."

The Institute focused on two other questionable elements of this package beyond its cost. One is the price signal: if the price of anything goes up, that's a message to consumers that they should look for ways to use less of it. But if gas prices are capped, that incentive is also capped, and the transition to alternative sources or lower energy use is slowed.

Feel free to take my own example: I'm thinking of getting solar panels installed on the roof. The higher the cost of electricity from the grid, the more attractive it becomes to invest in something that replaces it. So the calculation on whether that makes financial sense or not - leaving aside the environmental case - is changed by the price guarantee on electricity.

So on current assumptions, for every £1 spent on energy, the UK government will be paying 75 pence. As billpayers, we are therefore paying less than the economic cost, we have less incentive to reduce demand. And therefore on a limited supply, with prices capped, rationing is one possible consequence, even if the new prime minister says it won't happen on her watch.

Then there's the targeting. The IFS calculates that the package of support - including the Energy Price Guarantee, plus £400 per household, plus £150 off many people's council tax bills, plus a range of grants for those on benefits totting up to a potential extra £1,200 - should bring £1,600 of benefits to the poorest tenth of households, while it is worth £2,000 to the top tenth for income.

While, according to the IFS, households tend to spend similar amounts on energy, the share of their income that goes on it is very different. The benefit should be worth 14% of income to the lowest earners, and 5% to the top earners. So the same amount of money to a high earner is less effective at going where it's needed. Just over half of this support package goes to the better-off half of people.

It's something like the blunderbuss - that early form of shotgun that scattered pellets in all directions, which could prove useful over a short distance but was hopeless over the longer range.

The IFS goes on to point out that targeting the funds at the lowest income tenth of households still fails to reach the people most in need.

It says one quarter of that low pay decile pay bills of less than £1,250 a year, while a different quarter will be paying more than £3,500, even after they've prices guaranteed. Either they live in hard-to-heat homes or they have greater need of warmth, for reasons of age or medical conditions. Or both.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research takes a similar view to the IFS, but with different assumptions about energy use by better off households, it seems even more skewed towards those who least need the help.

It says the lowest income tenth save around £1,200 or 8% of their income, while the highest income tenth of households save more than £2,000, thanks to government borrowing, or 1% of income.

It had suggested a tapered subsidy, which is withdrawn the more energy a household uses.

Max Mosley, an NIESR economist, said: "The prime minister's energy plan is appropriate in terms of scale and ambition, but is needlessly inefficient and expensive.

"Its untargeted nature makes the currently unfunded proposal wasteful, which will put pressure on public finances, and for an unknown amount of time. There are better options, including a variable price cap that would have gone further in lowering the bills for the poorest and could have even paid for itself."

Taxpayer vs billpayer?

What about think tanks closer to Conservative government thinking? At the start of this month, before Liz Truss's announcement, the Social Market Foundation published its recommendation that funding a bailout for households had to come from a combination of taxpayers and billpayers, with their shares "to be negotiated".

"A 30-year funding facility for energy companies should be created, secured by collateral assets to encourage bank lending," it said.

"The cost of purchasing the collateral assets should be shared between taxpayers and shareholders in energy providers, on a basis to be negotiated.

"The facility should make loans that could be in place for up to 30 years, reflecting the fact it may take decades for providers to recoup, through household bills, the subsidy implicit in an artificially low cap".

The previous week, it had cited new survey evidence suggesting that the public was swinging behind a scheme targeted at those most in need of support.

The Institute of Economic Affairs, styling itself "the original free market think tank" is least impressed with the Liz Truss response. It is a firm believer in the price signal as a means of reducing demand.

Andy Mayer, its energy analyst, didn't hold back. He said: "The energy price freeze is middle class welfare on steroids. It represents a gigantic, untargeted handout to households funded by an increase in debt. It will mean future taxpayers subsidising hot tubs, heating swimming pools, and cooling wine cellars.

"Price controls don't work. The freeze will encourage more energy use, risking blackouts, and discouraging investment in energy saving.

"It would be better to use targeted welfare and tax cuts to help those who need it."

A blog on the IFS website cites the International Monetary Fund in its support, saying: "Many European governments have taken measures to delay the pass-through of wholesale to retail energy prices through tax reductions or price controls.

These measures are an inefficient tool to protect the economically vulnerable, are fiscally costly, and they mute the demand adjustment to the price shock, including energy-conserving behaviour and energy efficiency investments."

The IEA supports measures that compensate people after they have seen how much more their energy costs, again quoting the IMF: "Policy responses to the surge in energy costs should aim to preserve the price signal while providing targeted support.

"For households, lump-sum cash transfers, vouchers, or fixed discounts on utility bills are appropriate means of providing income support without distorting marginal energy prices, thus conserving the incentive to reduce energy consumption."

All that is before we consider the challenge for business and voluntary sector. Without a price cap, they have been facing soaring energy bills for months where they did not hedge in advance. Many of them face a new contract in October, if they can find a company willing to commit to a fixed price.

And although promised an equivalent level of support to households, though for six months rather than two years, it is not clear how the system will work in a fair way across business.

Some firms have low fixed rates, some have a complex buying strategy that includes some fixed and some flexible prices, which is where much of Scotland's public sector seems to be.

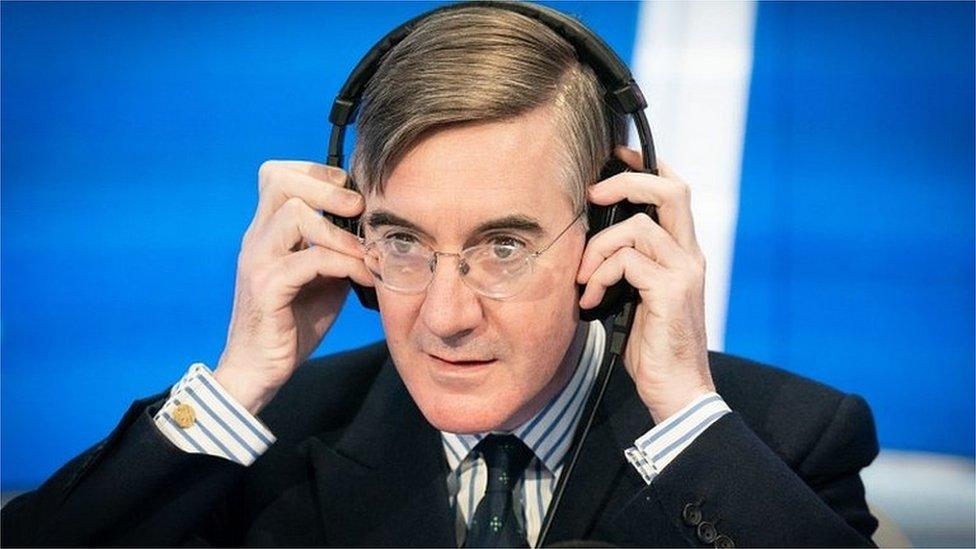

We're told today that the plan could be set out this Wednesday by the new business secretary, Jacob Rees-Mogg. That's after being told of the many ways in which this is very difficult policy to nail down.

From next April, once the initial promise to business has ended, policy could focus instead on government picking the most vulnerable and the most deserving companies. Choosing who qualifies will be even more weighted with difficulty.

- Published22 September 2022

- Published2 September 2022

- Published26 August 2022

- Published26 January 2023