Oil's bubble trouble

- Published

The rising oil price is fuelling inflation once more. It's seen by market analysts as reaching a "new normal".

Anti-oil protesters have driven a wedge between political parties and want to make the industry a pariah with other sectors.

While the oil majors seek to go greener, drilling is continuing through smaller firms with low-profile brands - but they say Britain's tax uncertainty is an obstacle.

It's pointing northwards again: the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil is a weathervane for the global economy.

The world benchmark has reached the highest level for 10 months, with the spot price peaking on Tuesday lunchtime at $95.72 before falling back a dollar.

That's lower than a year ago, and still $25 short of the peak reached in the turmoil of summer 2022, as many countries sought to pivot away from Russian energy supplies and to secure supplies for last winter.

In addition, the value of sterling has been sliding against the US dollar, from $1.31 to $1.24 since July 13, and the combined impact has pushed up the cost of fuel for transport and heating.

Market analysts think the co-ordinated supply constraints by Saudi Arabia and Russia will keep the price around $95, if not up to the $100 mark.

The oil market was surprised not that these two major exporters were continuing to dial back on production in order to keep the price up, but that they agreed to do so to the end of this year.

De-coupled

Rystad Energy published market analysis on Tuesday, saying the current price should be seen as the new normal for oil, with demand continuing to grow through to the end of this decade.

The consultancy says the lower prices associated with the recent cycles of boom and bust investment, which brought a glut of oil from fracking in the USA and prices in the mid-fifty dollar range, should be seen as abnormal.

The US was able, for a while, to control the dial on world prices, but that power to control supply seems to have passed back to the Saudi-led OPEC export cartel with its Russian friend.

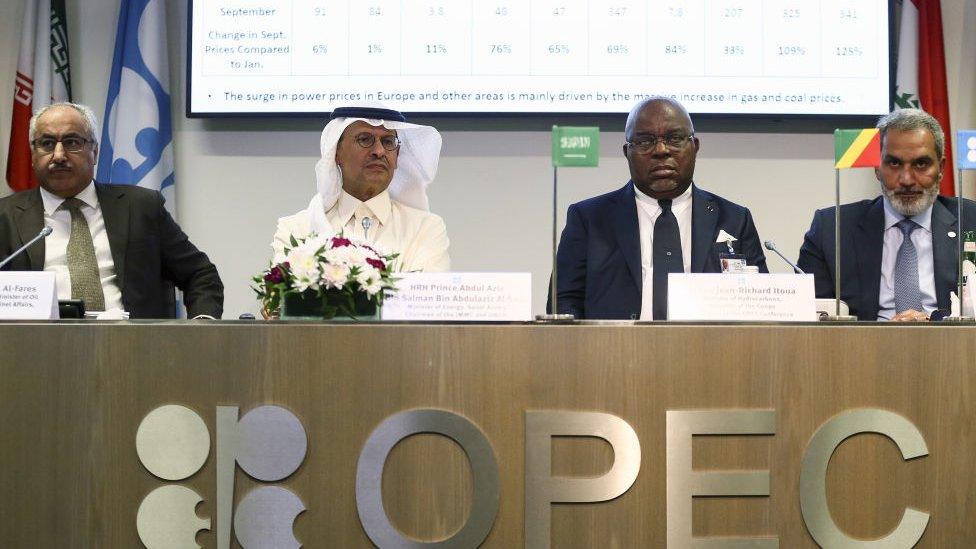

Opec has cut production to keep the oil price high

The less clear part of the market is whether demand is heading up or down. There are numerous conflicting signals, and for now, market sentiment is listening to the more positive ones for Chinese growth, and therefore increased energy demand.

This is a much more complex picture than it used to be. Economic growth required the fuel of oil, so demand went up. But that has been at least partly de-coupled.

It's possible to grow the economy while using less energy more efficiently, and sometimes because the transition to new energy sources is itself helping the economy.

Scottish ambiguity

The market is tangled with the politics and finance of net zero, in which this most important and influential of commodities is being shunned, for environmental reasons, by some of those people, countries and economies which are set to continue relying on it for years to come.

In the UK, the windfall profits from recent spikes in both oil and gas prices continue to mean much higher tax rates, currently at 75% of profits from UK waters, and continued tax uncertainty about whether a future Labour government will tighten investment allowances, or if lower prices, at least for gas, could see the tax eased.

And it is likely to play as one of the big issues separating the main parties in the Westminster election campaign, in which the SNP is trying for ambiguity: continued oil and gas if emissions are minimised or mitigated while trying to show leadership on the "just transition" to renewables energy.

Humza Yousaf wants Scotland to transition from the oil and gas capital of Europe to being a world leader in renewables

It's not such an easy message for Humza Yousaf to sell at the United Nations in New York while, back home, former SNP leader Alex Salmond says the approach is folly: "It would be plain daft to sacrifice such an overwhelming bounty for Scotland when Scotland's oil and gas can be the engine room of an independent Scotland and the resource which is used to fund the development of a Net Zero future."

Meanwhile, the politics of energy have got creatives in a spin. According to The Drum, news website for the advertising industry, influencers are shunning renewable energy for fear of being accused of green-washing, but at the same time, the oil and gas industry wants to use their media power to further its arguments.

One analysis of numerous contracts awarded in the PR industry, by the campaign group Clean Creatives, illustrates just how hard the oil and gas sector is working to fight its corner.

That group is putting pressure on advertising agencies to distance themselves from such work under a threat of being tainted in the eyes of anti-oil campaigners and other clients.

'Short-cycle, high-return'

We know the big public brands that drill worldwide and sell from the forecourt, such as Shell and BP, are struggling to avoid brand damage from campaigns against the industry.

A month ago, Bernard Looney, BP's chief executive, was saying the industry required "stability and predictability" from government. That looked an unfortunate irony last week when he left abruptly over inappropriate relationships with staff.

The company, meanwhile, was quietly pocketing a UK government licence to re-develop the Murlach field, 125 miles east of Aberdeen - one of around a hundred licences Rishi Sunak says he wants to award.

The bigger players can claim to mitigate some of this drilling activity with 14 companies gaining 21 licences, also granted last week, for the storage of captured carbon.

It's claimed these could be storing a tenth of the UK's emissions by the end of the decade, in carbon sinks covering a sea area the size of Yorkshire. Others in the industry are sceptical about that timescale.

While majors see a $95 oil price as the time to get back to investing, the battle over their brands opens up opportunities for smaller oil and gas companies. They have less reason to worry about their public images while private equity and other countries' wealth funds continue to back them.

For a flavour of what's going on, here is just some recent news from big though less well-known UK drillers, mostly based in Scotland:

Ithaca Energy announced it is taking over Shell's 30% stake in the Cambo field west of Shetland. Under protester pressure, Shell had said it was not willing to invest in production from Cambo.

But without such brand and public pressure, Ithaca now has 100%, and will only pay out to Shell once production starts and the earnings start to roll in, or if it sells on that stake.

Harbour Energy, which can claim to be Britain's biggest oil producer, set out plans to increase its investment in drilling "short-cycle, high-return" projects, apparently responding to the Treasury's investment incentives, which let it avoid some of the windfall tax.

But without mentioning the election, it warned that beyond next year lies uncertainty. It is looking to diversify away from its exposure to Britain's tax volatility, with mergers and acquisitions.

Harbour is one of those firms pushing into carbon capture and storage, including a role in the Acorn project based around north-east Scotland.

Enquest, based in London and Aberdeen and with UK and Malaysian assets, says its focus is on "mature late-life assets, responsibly optimising production to provide energy security. Where we can, we repurpose our infrastructure to deliver renewable energy and decarbonisation projects".

It published half-year figures that put it into the red, which is quite an achievement at recent prices.

In the first half of last year, as commodity prices soared, it made a profit of $203m (£164m), but this year, that became a $21m (£17m) loss. A key contributor to that was the $76m (£61m) bill for the Energy Profits Levy, the UK windfall tax.

Those financial results took 13% off the share price. In the past year, it has halved. That contributes to the difficulty of continuing to invest in UK waters.

Said the chief executive: "The UK's oil and gas sector faces significant challenges and loss of competitiveness due to uncertainty following the adverse changes to the fiscal regime".

Capricorn used to be Cairn Energy, based in Edinburgh and founded by ex-Scotland rugby star Sir Bill Gammell. Having got very lucky drilling in India, it moved on to try, very controversially, and to fail off the coast of Greenland, then had more luck in Senegal while investing in UK offshore assets.

But a shareholder revolt earlier this year has seen a sharp change of direction. Again, higher UK tax has encouraged it to exit British investment.

New management has sold all its assets apart from reserves in Egypt, handed shareholders hundreds of millions of dollars from its drilling war-chest, and shed 80% of its UK-based staff. Only 30 remain in a smaller Edinburgh headquarters.

The London office is being closed, and there are only 20 more staff, in Cairo - another Scottish corporate success story that is running, literally, into the sand.

Related topics

- Published19 September 2023

- Published6 September 2023

- Published18 September 2023