The Scottish National Party at 80

- Published

The SNP has been campaigning for independence since it was formed on 7 April, 1934

Every single-issue campaign group or minority starts with a dream. A dream to one day be in the position to achieve what it sets out to do.

Many fall by the wayside, but the Scottish National Party - which formed 80 years ago this month - is one of the exceptions.

It's taken a while to get there, but, despite the party's turbulent history, it will stage a referendum on Scottish independence on 18 September, after winning two historic terms in office.

The story of the SNP is one of success and failure, highs and lows, rogues and visionaries - but, most of all, it's the story of a party which started life on the fringes and became a mainstream force.

The modern case for Scottish home rule goes right back to its unification with England in 1707.

Fundamentalists V gradualists

The view that the Scots who put their names to the Act of Union had been bribed, famously spurred Robert Burns to later write: "We are bought and sold for English gold. Such a parcel of rogues in a nation."

Fast forward many years and those fighting for Scottish autonomy concluded that a pro-independence, election-fighting party was the way to go.

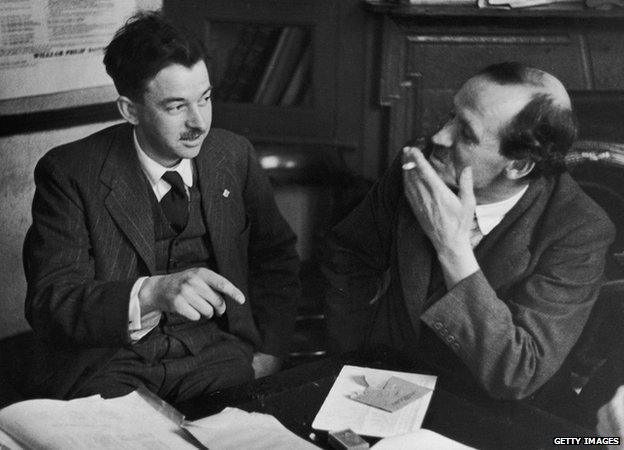

And so on Saturday 7 April 1934 at Glasgow's St Andrew's Hall, the Scottish National Party - an amalgamation of the Scottish Party and the National Party of Scotland - was formally inaugurated.

But for years the SNP struggled to make an impact, partly due to the ongoing debate between those who wanted to concentrate on outright independence - the fundamentalists - and those who wanted to achieve it through policies such as devolution - the gradualists.

Robert McIntyre's win in the 1945 Motherwell and Wishaw by-election was a key early success for the SNP

The young party's other problem was that, put simply, it just wasn't any good at fighting elections, because of its lack of funding, organisation and policies beyond independence.

In its first test, the 1935 General Election, the SNP contested eight seats and won none.

It was not until a decade later, at the Motherwell and Wishaw by-election, when the party finally got a break.

When the contest was announced following the death of sitting Labour MP James Walker, the nationalists sent in one of their up-and-comers, Robert McIntyre.

Standing largely on a platform of government failures in post-war reconstruction, the SNP took the seat with 50% of the vote, but lost it months later in the election.

A lack of electoral impact forced the party to reorganise - a move which would help the SNP to an even more famous win.

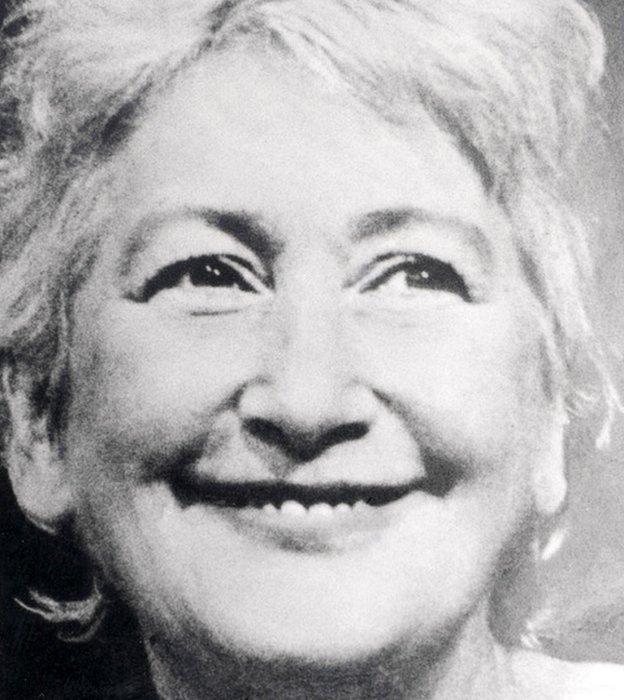

Winnie Ewing won the 1967 Hamilton by-election, declaring "Stop the world, Scotland wants to get on."

Margo MacDonald pulled off a stunning SNP win in the 1973 Glasgow Govan by-election

The 1967 Hamilton by-election should have been a breeze for Labour, but, as the party's vote collapsed, the SNP's Winnie Ewing romped home on 46%, declaring: "Stop the world, Scotland wants to get on."

The 1970s was the decade of boom and bust for the SNP. They failed to hang on in Hamilton, but 1970 brought the SNP its first UK election gain, in the Western Isles.

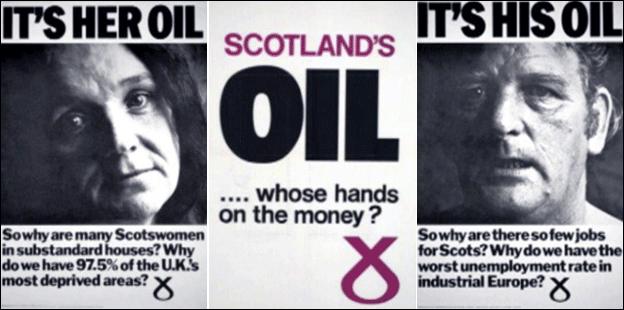

That same decade also saw the beginnings of the party's "It's Scotland's Oil" strategy, which sought to demonstrate Scotland was seeing little direct benefit of the tax wealth brought by North Sea oil and gas.

More success followed in 1973, when Margo MacDonald won the Glasgow Govan by-election and, the following year, an under-fire Tory government called an election, which it lost.

The SNP gained six seats and retained the Western Isles, but lost Govan.

With Labour in power as a minority government, the party had little choice but to call a second election in 1974 - but not before committing support for a Scottish Assembly.

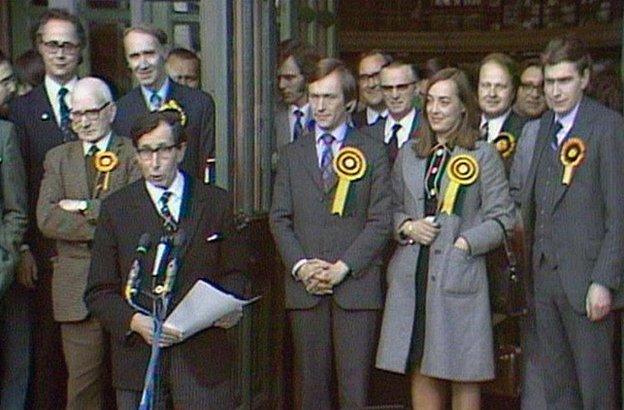

Even so, the SNP gained a further four seats, hitting its all time Westminster high of 11.

The SNP's 70s boom years peaked with the election of 11 MPs to Westminster in 1974

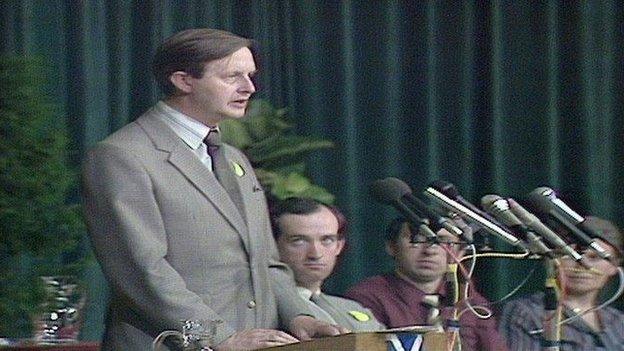

The party's turn of fortunes was largely down to its visionary leader-of-the-day, Billy Wolfe.

Despite the success, tensions began to develop between those in the SNP who were elected and those who were not.

Then came 1979 - the year which provided two serious blows to the SNP.

Margaret Thatcher's Tories swept to power, and a referendum for a devolved Scottish Assembly resulted in a "No" vote.

To be more precise, a requirement that 40% of the total Scottish electorate had to vote "Yes" for the 1979 referendum to become law, was not met.

With the constitutional issue off the table, the SNP came under a period of heavy fire from rivals, portrayed by Labour as the "Tartan Tories" and irrelevant "Separatists" by the Conservatives.

With a post-election SNP slashed back to two MPs, the party needed a serious jump-start - but that jump-start dragged the party into a period which could have finished it off for good.

The start of the 80s was a torrid time for the SNP when deep divisions gave rise to two notorious splinter groups.

'79 Group members, including future Scottish ministers Kenny MacAskill and Stewart Stevenson, seen here at the front of the line, were expelled from the SNP

Gordon Wilson, the SNP's leader at the time took the action he saw was needed to unite the party

One was the ultra-nationalist organisation Siol Nan Gaidheal - branded "proto fascists" by the then SNP leader Gordon Wilson.

The other was the Interim Committee for Political Discussion - more infamously known as the '79 Group, formed to sharpen the party's message and appeal to dissident Labour voters.

But the party leadership was unimpressed, and when a leak of '79 Group minutes to the media raised the prospect of links with the Provisional Sinn Fein - despite claims the leaked version was inaccurate - Mr Wilson had had enough.

His view that the party had to unite or die led to a ban on organised groups, but when the '79 Group refused to go quietly, several members were briefly expelled from the party.

They included Scotland's future justice secretary, Kenny MacAskill, and one Alex Salmond.

The 1987 election saw another bad SNP performance, emerging with only three seats.

But, towards the end of the decade, were things looking up?

Former Labour MP Jim Sillars, who defected to the SNP in the early 80s before becoming the architect of its independence in Europe policy, re-took Glasgow Govan for the SNP in a 1988 by-election - repeating the success of wife, Ms McDonald, more than a decade earlier.

And a collapse in the Conservative vote in 1987 meant the constitutional issue was back.

Now the party needed new blood at the top to take it forward into the next decade.

Few people have done more to aid the success of the SNP than Alex Salmond.

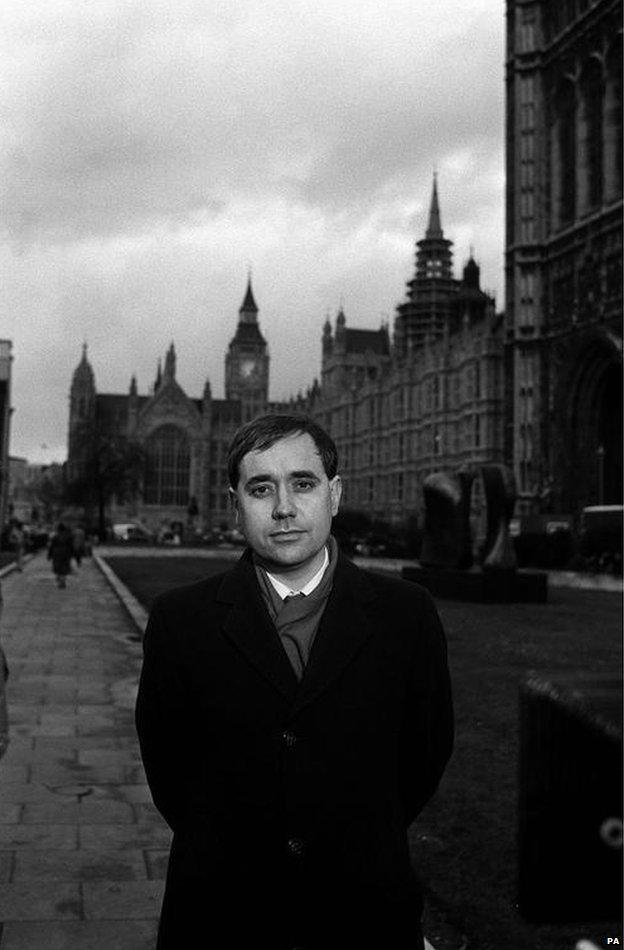

Despite previous form with the '79 Group, Mr Salmond had risen through the SNP ranks, becoming MP for Banff and Buchan in 1987.

He did not have his work to seek on becoming leader in 1990.

Alex Salmond's parliamentary career began when he was elected MP for Banff and Buchan in 1987

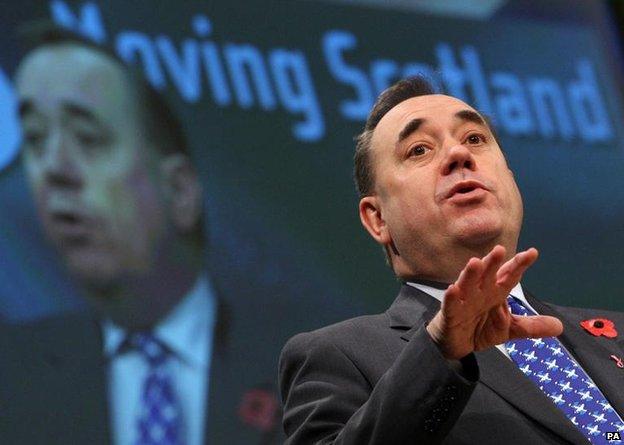

Mr Salmond led the SNP to its first Scottish election win in 2007

The SNP, under Mr Salmond's leadership, achieved its greatest success with a landslide election win in 2011

As well as having to deal with on-going internal issues over the party's independence policy - future minister Alex Neil had declared Scotland would be "free by '93" - there was an election to fight.

In 1992, the SNP increased its vote, but the party was only able to retain the three seats it already had, and lost Govan.

Mr Salmond moved to modernise the SNP to be more socially democratic and pro-European.

For the SNP, the best it could manage in the first devolved election of 1999 was to become the main opposition to the Labour-Lib Dem coalition government.

Then came Mr Salmond's surprising decision to quit as SNP leader, and as an MSP.

His successor in 2000 was John Swinney, but, despite being among the party's brightest talent, the future Scottish finance secretary's four-year tenure was plagued by dissenters from within.

The SNP's "It's Scotland's Oil" drive has become one of the party's best-known campaign slogans and is still used today

The party dropped a seat in the 2001 UK election, and, despite a slick campaign in the 2003 Holyrood polls, the SNP once again ended up the opposition.

Later that year, a little-known SNP activist called Bill Wilson challenged Mr Swinney for the leadership, accusing him of ducking responsibility for a "plummeting" SNP vote.

Mr Swinney won a decisive victory, discarding his usual measured oratory during a hustings to declare his goal was "to tell the Brits to get off".

But he was left weakened, and, at Holyrood, SNP MSPs Bruce McFee and Adam Ingram declared they would not support Mr Swinney in a leadership ballot.

Another, nationalist MSP, Campbell Martin, was flung out of the party after bosses found his criticism of the Swinney leadership damaged its interests in the run-up to the SNP's poor European election showing in 2004, where it failed to overtake Labour.

Mr Swinney quit as leader, accepting responsibility for failing to sell the party's message - but warned SNP members over the damage caused by "the loose and dangerous talk of the few".

When the leaderless party turned to Mr Salmond, he responded by borrowing from Union Army General William Sherman, who, on being asked to run for president following the American Civil War, declared: "If nominated I'll decline. If drafted I'll defer. And if elected I'll resign."

But ever full of surprises, Mr Salmond entered the leadership race, "with a degree of surprise and humility, but with a renewed determination".

Essentially, as he put it himself: "I changed my mind."

Nobody thought the 2007 Scottish election result could be so close.

In the end, the SNP won the election by one seat, while Mr Salmond returned to Holyrood as MSP for Gordon.

With the SNP's pro-independence stance ruling out a coalition with one of the other big parties, the party forged ahead as a minority government.

John Swinney quit as SNP leader after the party failed to overtake Labour in the 2004 European election

The SNP government had promised to seek consensus on an issue-by-issue basis, but when the opposition parties thought ministers were being disingenuous, they converged to reject the Scottish budget in 2009.

It was passed on the second attempt, but served as a reminder to the SNP the delicate position it was in.

Other key manifesto commitments also ran into trouble - plans to replace council tax with local income tax were dropped due to lack of support, while ambitious plans to cut class sizes in the early primary school years ran into problems.

Eventually, the bill on an independence referendum was ditched.

Although the SNP's focus had become the Scottish government, it was keen not to lose sight of its status beyond the Holyrood bubble and, in 2009, won the largest share of the Scottish vote in the European election for the first time.

Continuing its knack for winning safe Labour seats in by-elections, the SNP delivered a crushing blow to Labour, winning Glasgow East by overturning a majority of 13,507 to win by just a few hundred votes.

The SNP went into the 2011 election campaign with Labour leading in the polls, but the party failed to repeat this success a few months later in the Glenrothes by-election and, later, in Glasgow North East.

The Scottish government has been making the case for independence in its White Paper

In a story that bore echoes of the past for the SNP, the 2010 UK election saw Labour regain Glasgow East.

The 2011 Holyrood election was seen by some as Labour's to lose. In the event, that's exactly what happened.

Despite polls predicting a Labour lead over the SNP of up to 15 points, the nationalists threw themselves into the campaign.

They said their positive campaign, versus Labour's negativity, was what won it for them.

The SNP's 2007 win was rightly described as a historic one - but, four years later, the party re-wrote the history books.

The part-PR/part-constituency system at Holyrood was essentially designed to keep any one party (ie, the SNP) from winning an overall majority.

'No U-turns'

Scotland's first majority government named the date for the referendum as 18 September 2014, and launched its prospectus for the future in a White Paper.

But before all that, there was one big hurdle to clear.

The SNP's opposition to all things nuclear has always been as fundamental as its support for independence itself.

For many years it opposed membership of Nato, characterising the security alliance as one with a "first-strike" nuclear policy.

SNP Westminster leader Angus Robertson said a fresh approach was needed ahead of the referendum - although part of the argument for Nato within the SNP rested on a pragmatic calculation that most voters favoured membership.

Angus Robertson and Angus MacNeil, who put forward the Nato policy change, got their wish, but there was a cost to the party.

And so, at the party's 2012 conference, members voted to end the decades-old opposition to Nato membership.

But the decision didn't come without cost, and after a heated debate which invoked memories of SNP conferences past, two MSPs - Jean Urquhart and John Finnie - quit the party.

But it seemed the party managed to move on from the episode, and today, the SNP, with its 25,000-strong membership, has truly come a long way since the fringes of 1934.

But it now faces what could be a make-or-break challenge.

Labour veteran George Robertson famously quipped devolution would "kill nationalism stone dead".

But, with the SNP claiming rising support for a "Yes" vote, could the situation now be more akin to comments by another Labour stalwart, Tam Dalyell, who described devolution as "a motorway to independence with no U-turns and no exits?"

It's a question which will not only define the future of Britain, but the future of the Scottish National Party.