The dominant issue is back

- Published

Jobs and the economy re-emerged today as the dominant issue on the referendum campaign - or, to be precise, that portion of the campaign tracked by the wicked media.

In truth, of course, it never went away.

Individual folk will want to talk about individual issues including some, like health and education, which are already devolved and in Scottish control.

Incidentally, no harm to them for that.

Firstly, the Scottish government's White Paper, external contains both the proposals for independence and an array of decisions which might be taken by the elected government under independence.

Hence, it is relevant to consider broad policy, within constraints.

Secondly, it is decidedly relevant to contemplate the financial underpinning which would support the superstructure of public provision.

Which brings us back to the economy - and, once again, to the thought that it never went away.

Better or worse?

For most folk, this referendum involves a calculation. Would my family be better or worse off?

In that sense, it's not macro, nor micro. It's personal. It is about the household economy.

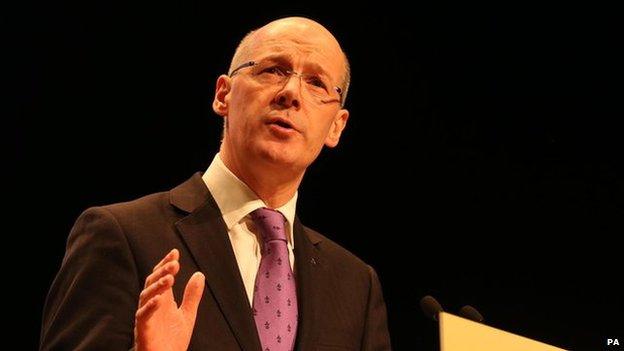

In which regard, Finance Secretary John Swinney set out a ten point plan for enhancing Scotland's economic prospects.

It focused upon manufacturing, capital investment and apprenticeships - with a proposed three pence cut in corporation tax in order to attract companies to Scotland.

And the response from Danny Alexander, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury? He described it as a "steaming pile of nonsense".

Business in Scotland, he argued, generally favoured retaining the UK.

John Swinney set out a ten point plan for enhancing Scotland's economic prospects

For his part, Mr Alexander was in Govan to confirm the contract for three new offshore patrol vessels to be built on the Clyde.

He made his announcement surrounded by sundry sections of the second aircraft carrier under construction for the Royal Navy.

The chief secretary argued that such contracts would not be available in the event of independence as the UK (or the remainder thereof) would direct orders to rUK yards.

And the response from John Swinney? A little more circumspect - but still forceful.

An independent Scottish government would place naval orders on the Clyde - plus the Scottish yards would still be best placed to attract work from the remainder of the UK, contrary to the assertions by Mr Alexander.

'Attack line'

Guess what Danny Alexander also wanted to mention?

You've got it. The currency.

It has become the default attack line for those opposing independence.

To be fair to Alistair Darling, he has been pursuing this path for months, indeed for years. He now has a considerable posse in his wake.

As this column has repeatedly noted, Alex Salmond is in a particular bind with regard to this issue.

His offer of retaining the pound is predicated upon agreement with another party. The snag is that other party is the UK government, of whatever colour - and it suits the precise political interests of the other party to say "no deal".

It may or may not be the case that such statements are bluff, that they would change in the event of a vote for independence, driven by a claimed economic downside for rUK including transaction costs and potentially being stuck with all the UK's debt.

For now, though, the party of the second part won't budge (with the exception of an unnamed minister quoted by the Guardian, external). To repeat, it is in their political interests so to do.

Which leaves Mr Salmond in a quandary. What, asks Mr Darling, is your Plan B? The cry is taken up by others.

Voters looking on perhaps think: what is the problem, why can't an alternative be produced?

Danny Alexander called the ten point plan a "steaming pile of nonsense"

But consider this. Say Mr Salmond offered an alternative, a Plan B. What then would be the response of his opponents?

Would they say: fine, thanks, about time too; better a sinner repenting?

They would not. They would seize upon Plan B and attempt to tear it to bits.

The euro? Cue widespread derision, translated from Greek and Portuguese.

Unilateral use of sterling? Cue talk of Panama and Montenegro, with complaints about lack of banking control.

A separate Scottish currency, then? Cue talk that the global markets would distrust a new currency with, inevitably, no history of trading.

There would be talk, more generally, of uncertainty.

Plan A? Plan B? What is going on? People want clear answers. What will happen?

'Public support'

Consider further. Just why does Mr Salmond offer the pound at all? Because the voters want to keep it.

Glancing at opinion polls, some advocates of independence say that evidence of public support for the pound in Scotland means folk are in tune with the wider Scottish government offer.

I reckon that is a posteriori reasoning. Folk back independence because they support the pound?

What if they just want to keep the currency - and are, in practice, offering no verdict upon the constitutional offer?

Mr Salmond is well aware of that Scottish attachment to the currency, derived from custom, practice and fear of the euro.

Hence, he features it in his independence offer alongside the maintenance of other elements such as the monarchy. It is part of the strategy of reassurance.

To be clear, there are advocates of a separate currency under independence. Intelligent, thoughtful advocates. It is Mr Salmond's belief that offering a range of options on the currency would also carry a political downside.

He is now caught in a bind of his own making - although, arguably, there is a degree of inevitability, given the wider desire to placate voters.

Consider further still. If the desire for independence in Scotland were all pervasive and all consuming, the currency issue would matter relatively little. It would be trumped.

Scotland, though, is divided. In that sense, then, the offer of retaining a currency which is perceived as strong is designed to remedy a perceived relative weakness.

There will be more on this. Much more.