What is the National Grid and why does it cost to connect to it?

- Published

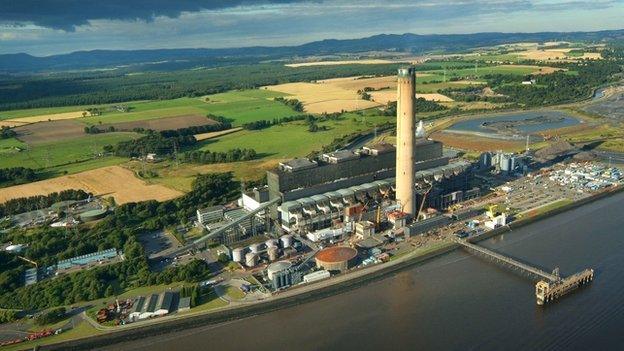

The owners of Scotland's largest power plant say its future is uncertain because of the £40m annual fee it has to pay to be connected to the National Grid.

Scottish Power believes its coal-fired station, Longannet in Fife, is at a serious disadvantage to English-based suppliers which can more easily tap into the network.

Here we look at what the National Grid is, where it is based and why it is harder for Scotland to connect to it.

What is the National Grid?

The National Grid is Britain's transmission system for electricity. In order to get from power stations to homes and businesses around the country, energy passes through the grid's pylons and cables.

It has been operating since 1933, when it first started carrying electricity across the countries and into homes. By 1946, 80% of households were connected to the grid by pre-wired electricity supplies in houses. In the 1950s, construction began on a new "super grid", which included new 42-metre pylons and more than 4,500 new transmission lines.

Today, National Grid plc, external is the company appointed by Ofgem to manage Britain's grid and the entirely separate network of gas pipelines.

It owns and maintains the high-voltage electricity transmission network in England and Wales. Scotland has its own electricity networks, run by SSE (Scottish and Southern Energy), external and SP Energy Networks, external.

Where is the National Grid?

The grid is UK-wide, so that if a local power station breaks down, another can supply power to its area.

There are two control centres - one for the northern half of Britain, and the other for the southern half. Their exact locations are a secret.

It is also linked by interconnectors to France, the Netherlands and Northern Ireland, which means that countries that have a surplus of electricity can send it to ones that are lacking.

Why is it harder for Scotland to connect to the grid?

Generators are the device at the centre of most power stations that convert mechanical power into electrical power.

In order to be connected to the National Grid, generators have to pay a transmission charge - but the charge varies depending on location.

Those generators that are far from the main centre of demand will be charged more more because it costs more to transport the energy further - maintaining long power lines requires more maintenance.

The further the plant is from London and the South East - the most densely populated areas - the higher the charges.

The aim of the higher fees is to encourage power companies to invest in generation capacity where it's most needed.

But it is not always easy to build plants in the areas with lowest transmission charges, as Paul Younger, professor of Energy Engineering at the University of Glasgow, explains.

He told the BBC: "Ironically, getting planning permission for power generation close to densely-populated areas is very difficult, so National Grid is trying to force things one way, where planning policies are trying to force them the other."

Why does it cost so much?

Electricity is sent through the National Grid cables at very high voltages - between 132,000 and 400,000. It benefits National Grid to not have to keep investing in reinforcing the high-voltage grid necessary to transport the power long distances. That's why Southern English generators pay reduced charges - and sometimes they even receive payments.

This is unlike most of Europe, where generators pay a flat fee to connect to the rest of the grid.

Longannet, a Fife power station that burns coal to produce electricity for the grid, pays about £40m a year just to be connected to the National Grid purely because of its location. It is relatively far from the centres of highest demand.

Suppliers - energy companies such as Scottish Power - also pay charges to take power from the network and supply it to their customers. According to Ofgem, this accounts for about 4% of a household energy bill.

How important is the transmission charge to the future of Longannet?

Its owners Scottish Power says it is very important. They insist that Fife's Longannet power station, the second largest in the UK, might have to close because of the £40m annual fee it pays to connect to the National Grid.

Scottish Power, which supplies electricity and gas to UK homes and businesses, said this puts it at a disadvantage when competing with UK plants.

This year, the UK government is running the first "capacity market auction", where suppliers bid to guarantee electricity generation for the winter of 2018/19.

But Scottish Power has decided not to enter the Longannet plant, saying that financial changes need to be made or the plant will have to close.

Is there change in sight?

In July, Ofgem said it was going to change the way it calculated, external what generators pay to use the electricity transmission network. It said: "Analysis indicates the changes will lead to a more efficient system which will benefit customers."

The changes are not due to come into effect until 1 April 2016 - but Ofgem say that their updated methodology will reduce the north and south divide in transmission charges.

In the short term, Scotland's energy minister Fergus Ewing wants more urgent action. He claims Longannet is being priced out of the market.

Longannet powers about two million homes - so if it closes, Scotland's power supply will be affected.

Prof Younger said: "At a stroke it would remove the supply of about 25% of all electricity consumed in Scotland, which would make it very difficult to keep the lights on when the wind isn't blowing, without increasing reliance on power imports from England - for which there is not sufficient inter-connector capacity on the National Grid anyway."

- Published6 October 2014

- Published3 October 2014

- Published23 September 2014