The blast furnace of globalisation

- Published

Steel is something of a national virility symbol - not just for Scotland, Wales and northern England, but for emerging and emerged economies for whom it has been the first burst of industrialisation.

The blow to Scottish economic virility 22 years ago, with the closure of the Ravenscraig plant near Motherwell, was symbolic instead of the end of an era.

What remains of the industry is down to no more than 400 workers employed by Tata Steel at the Dalzell steel mill in Lanarkshire and the vast, historic Clydebridge works in Cambuslang.

Along with three distribution centres - in Edinburgh, Dundee and Mosstodloch in Moray - they're being sold by Tata, the Indian conglomerate, to Swiss-based American investor Gary Klesch, chairman of Klesch Group.

The Memorandum of Understanding has unions worried about the implications for jobs - 400 or so in Scotland, but more than 6,000 across the UK, often in regeneration troublespots.

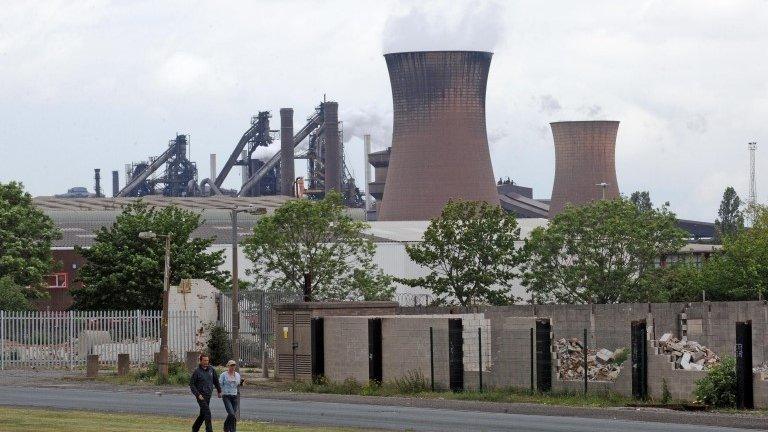

The Ravenscraig steel plant near Motherwell closed 22 years ago

Mr Klesch has been quoted as saying he wants to invest to grow the UK business. But he's buccaneering American with a track record in buying and marketing distressed assets, of robust turnarounds and of making enemies. It's not a reassuring CV for his steel future employees.

It's to the credit of the rather more patrician Tata Group, which took over the formerly nationalised British Steel assets from Corus in 2007, that trade unions wish the Indians would stay in charge, as they're used - except on this occasion - to being kept in the loop.

Long, flat and strip

What also makes them nervous about their future is that the offloading of part of Tata's UK and Dutch steel-making division is from a position of weakness rather than strength.

The bit that's being kept by Tata is in flat products, including strip steel, based around its Port Talbot steel plant in South Wales. Employing more than 11,000, it is a more profitable part of the business, and fits better with Tata's other businesses in the Netherlands and India.

At the time Tata took over the majority of Britain's steel capacity, in the wake of buying Tetley tea and Jaguar Land Rover, it was seen as wanting to learn about brands and about manufacturing. Having learned, it now seems it's moving into a new phase.

So the bit that's being sold is in long products, as opposed to flat products, which includes coils of strip steel. The long products start out in Scunthorpe, where as many as 4,000 people are employed.

The steel destined for pipework in the North Sea is processed in Corby and Hartlepool. That's staying with Tata, and so it's becoming part of the Flat Products division. The remainder of Long Products is bound for railways (a division which is doing quite well), for thick plates, wire rod and sections.

Those structural steel sections are important in the supply chain of big civil engineering products, such as bridges or high-rise buildings.

But the construction industry has been in dire straits over recent years. The bit that has recently recovered is in home-building, which is not as steel intensive as commercial and the infrastructure sector for which government austerity has been a blow.

Quenched and tempered

Demand for steel sections is about 50% to 60% of what it was at the unusually strong peak of the market in 2007. Europe's demand for steel in general is down by around a quarter since its pre-crisis peak.

The job of the Scottish plants is to roll slabs of plate metal at Dalzell. At the Clydebridge plant, they get "quenched and tempered" with heat treatment to make very strong steel, for use in mining, offshore oil and gas equipment, and heavy "yellow goods", such as cranes and diggers.

That has also had some rough times with demand, which has long ebbed and flowed with the economy. What's changed this time is that it's the supply of steel that's become the bigger problem.

European steelmakers grew up after 1945, and now look dated. American steelmakers benefit from much lower energy costs than in Europe, and of course, this is very energy-intensive manufacturing.

There's been plenty of growth in demand for steel in Asia, pushing global demand up by around 25% while Europe and North America were hit by recession.

But there's also been vast extra capacity added. China now makes half the world's steel. And with its economic growth cooling markedly, it can export its surplus.

Seen from Lanarkshire, as from Tees-side, the sale by Tata to Klesch adds more insecurity to past industrial blows. Yet this is very much part of the story of globalisation.

- Published15 October 2014