Sturgeon and Pym on landslides and successful government

- Published

Margaret Thatcher disagreed with Francis Pym's assertion

Remember Francis Pym? Chief Whip and Northern Ireland Secretary under Ted Heath? Later, Defence Secretary, Leader of the House and, finally, Foreign Secretary during the Falklands War?

That's the fella. Anyway, I thought idly of him as I listened to the first minister at her news conference today.

It goes without saying that I was paying rapt attention to Nicola Sturgeon - but a tiny portion of my cerebral matter was with Pym.

He it was who said on telly that "landslides don't on the whole produce successful governments." His boss, M. Thatcher, dissented rather sharply on the grounds that she coveted every Parliamentary seat going and was less than averse to a huge majority, as gargantuan as feasible.

Mr Pym was duly sacked after the 1983 general election, having earlier led a protracted campaign within the Cabinet against elements of the prime minister's economic policy.

I covered these affairs as an infant lobby correspondent at Westminster. Somehow, the memories resurfaced as I heard Nicola Sturgeon declare that minority government was probably, on balance, all things considered, good for democracy.

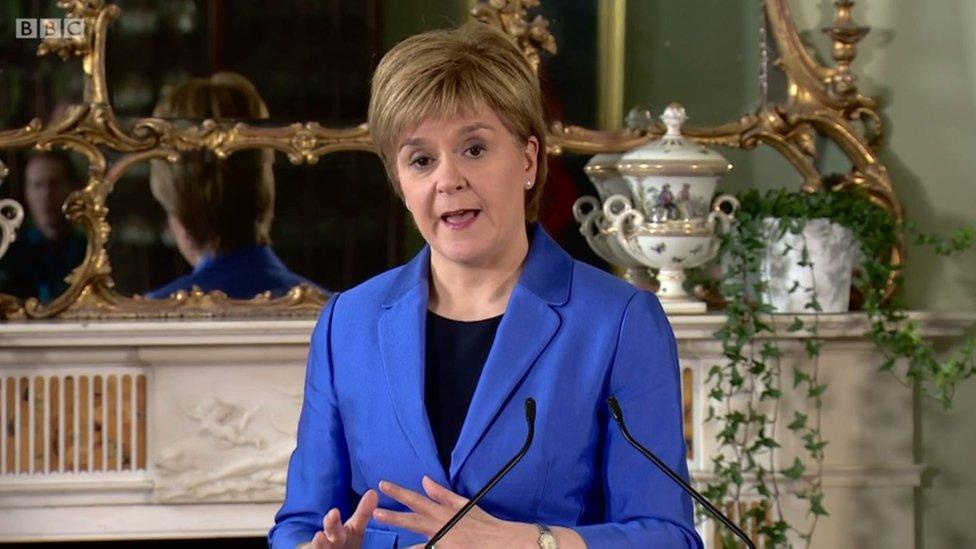

Nicola Sturgeon struck some conciliatory notes during her Bute House press conference

It was said, admittedly, with a gentle smile - but without a hint of evident irony. Are we then to accept that Ms Sturgeon prefers the absence of a majority, that she was glad the SNP lost ground on the list, having won constituencies?

I think not. She is simply dealing, with good grace, with the circumstances dictated by the voters. She is sounding content and consensual.

She added substance to this tone by suggesting she might face a longer session of weekly questions, that she might appear more frequently before committee conveners and that such conveners might be directly elected.

In addition, she indicated that she intends to reshape her cabinet, with separate cabinet secretaries covering the economy and tax, on the grounds that both these topics are set to be time-consuming in the period ahead. This change has been welcomed by opponents.

Balancing act

There are, however, limits to consensus. Ms Sturgeon declared that the SNP won the election and were, consequently, entitled to implement their manifesto, including their tax plans.

That statement, she said, was "notwithstanding" her earlier remarks about consensus. Herewith, in outline, a delicate balancing act in the making.

Essentially, Nicola Sturgeon's approach is to say that the SNP came so close to a majority - and so far ahead of their opponents - that the starting point for Parliament should be their manifesto. Not an amalgam of competing offers.

It is not, therefore, like a coalition where policies are traded, with some abandoned on both sides. It is not like a truly hung Parliament where the governing party readily concedes that some elements of its programme must be sidelined in order to achieve others.

The SNP are likely to seek to work with different parties on different issues at Holyrood

Ms Sturgeon does not, for example, envisage trading over tax policy. She envisages, rather, deploying persuasion in order to secure her own party's taxation plan.

In practice, that might involve gaining support from the Conservatives in that they favour tax moderation and are against a general increase. The SNP plan, of course, differs in that they want to reverse the chancellor's scheduled cut for upper earners.

However, these are forward matters. More generally, Ms Sturgeon talked of there being a "progressive majority" in Parliament - and of her intent to build upon that.

That would seem to indicate that she is more likely to look to Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats for support. Again, in practice, it will be a matter of forming different alliances according to the issue.

To repeat, though, the SNP remains in a strong position. It is hard to envisage an issue which would unite all the opposition parties in a coherent bloc, with the governing party on the other side. Persuasion and tactics would seek to pre-empt such a situation.

After his removal from cabinet, Francis Pym wrote a book entitled "The Politics of Consent." Perhaps Ms Sturgeon might pick up some tips.

Then again, maybe not. It is, as I recall, chiefly an account of the dissent which existed within the Thatcher Cabinet. Understandably, Ms Sturgeon wants none of that.

- Published11 May 2016

- Published8 May 2016

- Published6 May 2016