Scottish Labour heads for 'full autonomy'

- Published

Scottish Labour has won the backing of UK party bosses to become "fully autonomous", pending the approval of conference. But what exactly do the changes mean?

Is it devolution or independence?

Kezia Dugdale has welcomed plans to give more power to Labour in Scotland

It is a "huge", "substantial change", Kezia Dugdale says. The culmination of a year-long effort to boost the sovereignty of the Scottish Labour Party; at last it could be "fully autonomous".

Amid the leadership turmoil in Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party, many had predicted a split. This was not the one they had in mind. But in truth this is not really a secession; it is more a matter of devolution than of independence.

As Ms Dugdale puts it, this would see her party "fully autonomous within the UK Labour Party".

So what is this new relationship between the Labour parties which Ms Dugdale has her eye on, and how would it change things in Scotland?

It's important to stress right from the outset of course that this is just a proposition; it still needs to be approved by the Labour conference in Liverpool.

And despite the National Executive Committee's (NEC) freshly-conferred backing, it might not necessarily be a done deal - Labour's membership has grown so exponentially and from such varied quarters that the party's central office can't be entirely sure how it will react.

Where does the story begin?

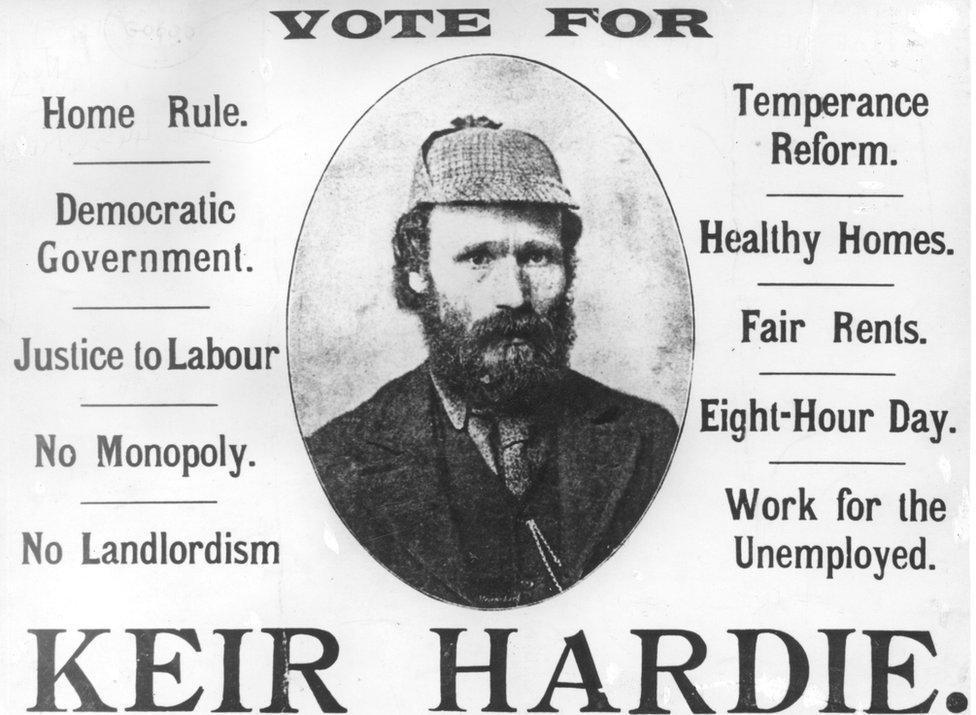

Keir Hardie started the Labour movement in Scotland and eventually led the Parliamentary Labour Party

There was actually a Scottish Labour Party before there was a UK Labour Party, dating back to 1888.

Lanarkshire-born Keir Hardie pioneered the Labour movement in Scotland, and eventually led the Parliamentary Labour Party at Westminster after being elected (in Wales).

In England and Wales, the Labour Representation Committee was set up in 1900, changing its name to the Labour Party in 1906, and amalgamating with its Scottish sister in 1909 to form the UK-wide body which exists today.

Scottish Labour really came into its own in 1999 with the establishment of the Scottish Parliament, gaining a host of MSPs and a leader in the form of the head of this MSP group.

Initially the party was a major force at Holyrood; effectively the leader of the Labour group was the First Minister. But as the party's electoral fortunes declined and it slipped into opposition, efforts to reform the party led to the creation of a formal position of "Leader of the Scottish Labour Party."

There have been three official Scottish Labour Leaders; Johann Lamont, Jim Murphy and Kezia Dugdale

But the first such leader, Johann Lamont, resigned in 2014, infamously accusing the UK party of treating the Scottish arm like a "branch office".

Labour's opponents seized on these comments gleefully; to an extent they've never been allowed to forget about them. In a way the latest moves remain an effort to make a clean break from that.

But really the hunger to reform Scottish Labour has been building ever since the Scottish Parliament was established, and in particular as the parliament's powers have grown.

The argument is that Scottish devolution and Holyrood's standing has moved with the times; the Labour Party has not.

Perhaps fittingly appropriating a phrase from the SNP - who have usurped Labour's dominant position in Scottish politics - Ms Dugdale says the new changes will make her party able to "stand up for Scotland".

Who will shape policy?

Scottish Labour conferences have already taken some controversial policy stands - like over Trident

The most eye-catching point in the latest "devolution" is the idea that Scottish Labour could set policy in all areas - including ones reserved to Westminster.

It's easy to see how conflicts could quickly arise between the Scottish and UK parties - in particular given the ideological differences between their leaders.

But - and this is a big but - this won't mean there will be a separate Scottish manifesto at UK elections.

Where a difference arises, there would be a resolution process to square the two parties' positions, to come up with a single platform for the party nation-wide.

Significantly Ms Dugdale would have a seat at what's called the Clause Five meeting, where Labour's policy platforms are decided before the general election, where she would have the chance to fight Scotland's corner.

A contemporary example; Scottish Labour's 2015 conference voted to oppose the renewal of Trident, while the UK-wide party, at the time of writing, formally backs it.

If this position were maintained prior to the next general election (a significant if, given Mr Corbyn's opposition to Trident), then there would be an internal debate to come up with a joint UK-wide policy, giving Ms Dugdale a chance to push her party's position - "standing up for Scotland", as she puts it.

How much clout the Scottish party would have in such negotiations is of course debatable - especially given the fact it currently only has one MP, and a dwindling stock of MSPs.

Will UK Labour still exist?

![Kezia Dugdale and Jeremy Corbyn [centre of picture] campaigned together](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/D74B/production/_90751155_leaders_ap.gif)

Ms Dugdale has said the UK-wide Labour "family" will stay together

The Labour Party has always been a broad organisation.

It encompasses Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs), affiliated trade unions, socialist societies like the Fabian Society, and the Co-operative Party - although the latter is registered as a separate entity with the Electoral Commission.

Talking of the Electoral Commission, they don't consider Scottish Labour (or indeed its Welsh equivalent) as separate parties as such; it is rather denoted as an "accounting unit". This is another point which the party's opponents have been known to crow over, but one which makes essentially no practical difference.

And that practical level is where things are changing, rather than a constitutional one.

Scottish Labour has its own executive committee, the SEC, its own leader and its own general secretary - but it remains part of the wider party, just as Scotland has its own government but remains part of the UK.

If the new changes are approved, then the Scottish party will have a growing role in the way the main party is run; it will gain a representative on the UK-wide NEC, nominated by Ms Dugdale, and a more direct say in the running of Scottish CLPs.

And the SEC would have responsibility for candidate selection procedures in Scotland for future general elections - something which could prove significant in itself given rumblings of rebellious MPs potentially facing deselection.

Who'll control the money?

Labour will hope this change in identity will help change their electoral fortunes

So what will UK Labour remain in control of? Principally, it will keep a firm grip on the purse-strings.

This is largely a practical matter: financial devolution would be incredibly difficult, given the unique way the Labour Party is funded.

A fair chunk of Labour's funding comes from those aforementioned affiliates, chiefly the trade unions, and the way this money is paid out is labyrinthine.

Sometimes the money goes to the UK party, sometimes to the Scottish one, sometimes even to individual candidates. Unpicking this knitting would be a nightmarish job.

To put it another way, extracting Scottish Labour from the UK party in terms of funding would be as complicated as, say, taking the UK out of the EU (*cough*).

But as noted above, the key ties which remain are emotional, almost philosophical ones; as Ms Dugdale puts it, the party remains a "collective", a "family".

The Labour Party was founded on values of cooperation, as a movement not just across a country but across the working class. On the back of party membership cards to this day is the phrase "by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone".

These new reforms seek both to cement Scottish Labour's individual identity and to give it a greater say in the running of the UK whole.

Both Ms Dugdale and Mr Corbyn will be hoping they can also go some way towards repairing the party's electoral fortunes both north and south of the border.

- Published21 September 2016