Looking back on the political gambles of May and Sturgeon

- Published

Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon have both thrown the dice with their stances on indyref2

It was a week of politics no one saw coming - first Nicola Sturgeon's fresh bid for a Scottish independence vote, second Theresa May's response of "not now". Here, I reflect on the actions of two normally cautious political leaders taking what could prove to be the biggest of gambles.

Calculated choreography

Ms Sturgeon upstaged the prime minister in what was meant to be a defining week of her government, as the bill giving her permission to trigger Article 50 and begin the Brexit process was passed. Indeed, many had expected Article 50 to be triggered in the days following Ms Sturgeon's announcement.

Thanks to the first minister's dramatic intervention, even as the Brexit bill received Royal assent Mrs May was drafting a statement about Scottish independence - not the constitutional issue she had hoped to be focusing on.

Mrs May's response was equally calculated to upstage Ms Sturgeon; her statement was recorded while the first minister was on her feet during her weekly question session at Holyrood, and broadcast to the world the minute she sat down.

And it came on the eve of the SNP's conference in Aberdeen, which ended up being dominated by the constitutional question - and not entirely in the campaign-rally fashion Ms Sturgeon would have wanted.

Timing

Theresa May: "We should be working together, not pulling apart"

What does Mrs May's announcement mean?

The phrase she was keenest to use "now is not the time" - but significantly she didn't say "never". So if not now, when?

Has she accepted that there will be an independence referendum sometime after Brexit?

Both sides say they want the Brexit picture to clear up, so they can offer voters an "informed choice". The divide is over when they believe this will happen.

Ms Sturgeon believes the substantive shape of the Brexit deal should be set in stone by roughly the Autumn of 2018, six months before the conclusion of the two-year Article 50 "window" - or at least by the end of said window in Spring 2019.

But the Westminster government contend that there will only be an informed view of the post-Brexit Union some time after the UK has actually left the EU, once trade deals have been hammered out and the new arrangements have had time to "bed in".

They don't want to get into speculation about what year that might be, but on those terms it doesn't seem likely a new vote could happen anytime before late 2020.

The Europe question

Might getting the Brexit process over and done with help the SNP and the pro-independence side?

Whether or not an independent Scotland would be a full member of the EU has been becoming something of a headache for Ms Sturgeon already.

It now seems clear that Scotland is leaving the EU, regardless of when a referendum is held and whether it is won.

This will please the various SNP members who supported Brexit - such as former cabinet secretary Alex Neil, who has warned Ms Sturgeon against having a "premature" referendum.

It seems that the SNP still want to target EU membership, somewhere down the road - but might take a step-by-step process towards that, perhaps through the European Economic Area.

Conducting a vote during the Brexit process makes that message harder to sell - people will wonder why it's so important to hold a vote before the UK leaves the EU, if Scotland is to leave regardless of the outcome.

However, there is one other dimension to Brexit: once the UK has left, EU nationals living in Scotland might not be able to vote in any new referendum - potentially a key demographic for the pro-independence side, underlined by the SNP conference motion aimed at protecting their franchise.

The Will of Parliament

Votes on many Holyrood motions are not binding

The Scottish government now argues that the Holyrood vote on a Section 30 order is more important than ever. In the end, it was the focus of Ms Sturgeon's big conference speech.

But Mrs May's response assumes that this vote will be approved. Ms Sturgeon doesn't take this for granted, but it should be in the bag - the Greens will back her, so if everyone turns up there is a 69 to 59 majority for independence.

In any case, the Presiding Officer has already confirmed that votes on motions like the one to be debated over two days are not binding. The chief point scored will be political.

After all, Holyrood has already voted against triggering Article 50, and that seems to be going ahead regardless.

And in some ways the SNP should be glad. The opposition have ganged up on them several times this term already - should they have to bow to "the will of parliament" all the time, they would have had to repeal the football act, ban fracking, give Highlands and Islands its own board and accept that they are "failing teachers, parents and pupils".

Party politics

There are still some party-political elements amid this grand constitutional row.

In particular, it has cast the SNP and the Conservatives as the two big players in Scottish politics. A newly confident Scottish Tory movement has firmly cemented its position as the party of the union, while the SNP are the ones taking the fight forward for independence.

Labour and the Lib Dems are left a relative afterthought on the unionist side; the Greens equally so on the independence side. Ms Sturgeon's conference speech made scant mention of those other parties - even Labour, the staple punching-bag of any SNP conference - while hammering away at the Tories.

This could have a knock-on effect in particular in the council elections - the Greens had been campaigning hard for that vote to be about local issues, but it's hard to imagine constitutional issues won't dominate on the doorsteps now.

Measuring mandates

Blocking a Scottish referendum 'would be undemocratic'

Ms Sturgeon argues that she has a "cast iron mandate" to push for a referendum thanks to the scenario sketched out in the SNP's 2016 election manifesto, which has come to pass with almost spooky accuracy.

But the Conservatives argue that the SNP didn't win a majority in that election - ignoring the fact the Holyrood electoral system is designed to make an outright majority more or less impossible.

Most of the "mandate" arguments are similarly muddy. There are points for both sides to score.

The SNP won a bigger percentage of the Holyrood constituency vote than the Tories took in the last Westminster election - and of course Mrs May's government has a single MP north of the border.

However that was a UK election, just as the EU referendum was about the UK's membership of the European club. And in that referendum, as many people voted Leave in Scotland as voted SNP a few weeks earlier (both figures just over 1m) - and both of those figures are dwarfed by the number who voted No in 2014.

David Mundell said he didn't want to get into "my mandate is bigger than your mandate", and he's probably right - there's enough ammunition for each side that this is not the field where the battle will be decided.

Sufficient support?

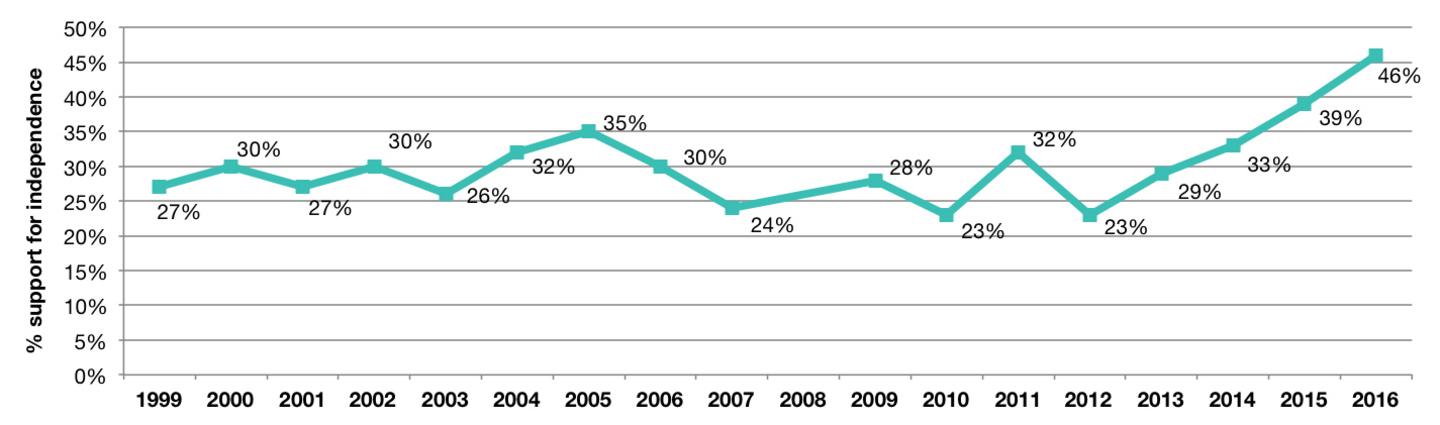

Support for independence since 1999

At the end of the day, there will be only one question that matters - and it will be a form of "should Scotland be an independent country?"

Theresa May's calculation is that she won't push too many people towards eventually answering that question with "Yes" by blocking the vote in the short term.

The SNP will welcome her refusal as a campaigning tool, if nothing else. And perhaps putting things back a bit wouldn't be the worst thing for the independence campaign.

Nicola Sturgeon's original preferred timetable, before all of this Brexit business happened, would have been a referendum sometime around 2020 - after the next Westminster election, but before the next Holyrood one.

The calculation would be that this will see another Tory government returned at Westminster (polling suggests the race there is about as close as the current Scottish Premiership season), allowing the SNP to hammer away with their 'ruled by a Tory government Scotland didn't vote for' narrative.

And it would give Ms Sturgeon more time to work on tricky economic arguments - there remain a lot of questions over matters like currency which remain unanswered.

The Scottish Social Attitudes Survey suggests support for independence is climbing fairly steadily - but it has not yet reached the majority.

As polling guru John Curtice said: "Nicola Sturgeon might have been wiser to have stayed her hand, for on current trends there is a real possibility that demographic change will help produce a majority for independence in the not too distant future anyway."

Breaking the impasse

What will it take to send Scotland back to the ballots?

So how will all this be resolved? At the moment, it seems like the two sides are locked in a bit of an impasse.

Could the SNP plough ahead and hold an "unauthorised" referendum? Possibly, but it would be even more of a risk - such a vote could get tied up in the courts before the ballot papers were even printed. Many at the SNP conference talked about how there "will" be a referendum but Scottish government officials say this is more because Mrs May's position is untenable, rather than a signal towards a consultative vote.

In the aftermath of Mrs May's statement, someone wryly observed to me that "maybe we should have a referendum on whether or not we have a referendum".

Is there a way that could happen? In a way it could, if the SNP were to sink their own government and push for a snap election on a very specific platform of holding a new referendum swiftly afterwards.

That would seem a rather unlikely scenario, for many of the reasons outlined above - there is no way Ms Sturgeon could be sure she would win such a vote. If indyref2 has the air of a make or break moment for her leadership, such an election would be doubly so.

But there is another significant Holyrood vote on the horizon - on the UK government's so-called "Great Repeal Bill" as part of the Brexit process.

The UK government has already confirmed that the Scottish Parliament's consent should be sought for that legislation.

Given the pro-independence majority, Holyrood could quite easily withhold that consent. And while the Supreme Court has noted that the Scottish Parliament can't legally derail Brexit via legislative consent, MSPs could give Mrs May a terrific headache from a political perspective.

Ignoring a legislative consent vote would be of far greater significance than ignoring the non-binding motion on Section 30.

So the message could be, "give us your referendum, and we'll give you your clean Brexit" - paving the way for a referendum sometime in 2019.

- Published16 March 2017

- Published16 March 2017

- Published10 April 2017