FMQs: stimulating debates on tax

- Published

Nicola Sturgeon set out a discussion paper with the aim of stimulating debate about taxation

The first minister is temporarily homeless. Officially, that is. Her Bute House domain is undergoing repairs.

And so she decanted to the comparably splendid surroundings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh to announce her options on income tax.

There she stood in the Scott Room, her finance secretary Derek Mackay at her side and a faintly austere portrait of the great man (Sir Walter, that is, not Mr Mackay) looming over the pair of them.

To add to the sense of history, there was a small but perfectly formed statue of David Hume in the corner. To add to the sense of mystery, the clock on the elegant mantelpiece was stopped. At 25 to nine, since you ask.

In keeping with these academic and ancient surroundings, Nicola Sturgeon opened by citing Adam Smith to the effect that taxation must be proportionate to the ability to pay.

She might equally have deployed another quote from the Wealth of Nations; that man is an animal that makes bargains. For Scottish ministers will need a deal to get their budget through.

Where might that deal come? The signs were in the tax document itself and in the Holyrood exchanges which followed, during questions to the FM.

The Scottish government paper, external, drawn up by the office of the Chief Economist, analyses the tax plans not just of the SNP but also of opposition parties.

Ms Sturgeon noted that she had received detailed submissions from the Liberal Democrats and the Greens; a brief paper from Labour which, she said, lacked detail on tax; and nothing from the Conservatives, who want to match UK tax rates and not, they argue, disadvantage Scotland.

However, the SG paper then goes on to cite four key tests for selecting Scotland's tax policy - and to outline four options.

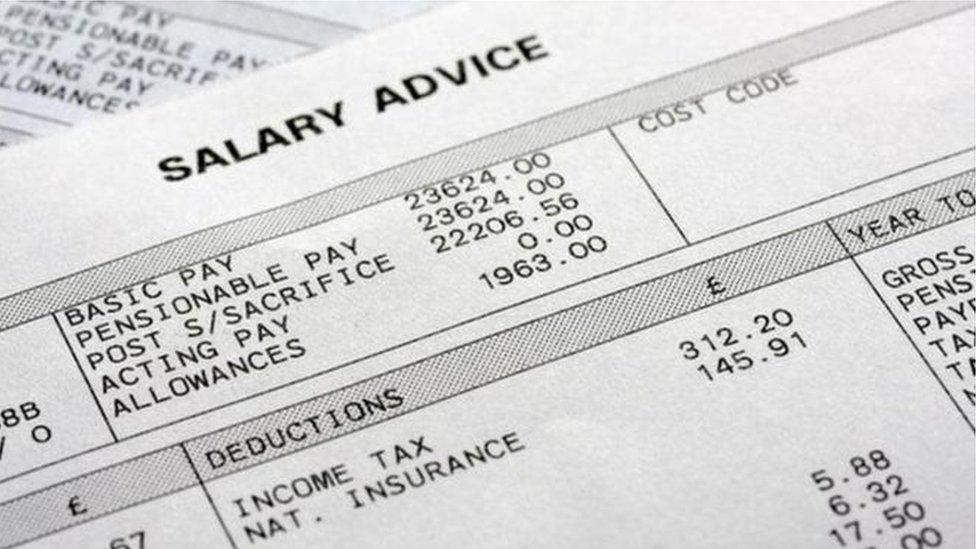

The tests include protecting the lowest earners. Ms Sturgeon made plain, again, that she disliked the notion of a general increase in the basic rate. Which takes out the plans advanced at the last election by Labour and the Liberal Democrats (although, to be fair, those might subsequently change just as the SNP has shifted its own position).

She made plain further that she disliked the Conservative proposal to match UK rates and bands which, she said, would involve a cut in spending and a bonus for the wealthy. Which takes out the Tories.

Not, you understand, that they were ever in, given their intention to make a strong stand on the Union and relatively low taxation.

Which leaves? The Greens. Yes, the party which did a deal with Mr Mackay last year. The party which advocated protecting the poorest and spreading the increased burden of tax across a broader range of bands.(It would be remiss of me to neglect to mention that the notion of new bands was first disclosed by me during the SNP conference).

So it was no surprise when Patrick Harvie appeared notably more content with the SG document than the leaders of other parties. Content, in outline, you understand. There will be a lot of hard bargaining to come.

Patrick Harvie was pleased with the contents of the paper

For one thing, the SG plans - even at their highest level - only raise around half the amount proposed by the Greens. Around £430m instead of £870m, in each case presuming no revenue cuts from behavioural changes (tax exiles fleeing to Carlisle or otherwise changing their revenue domicile).

For another, there are wider issues. The Greens remain resolutely opposed to plans to cut aviation tax in Scotland. Ministers may have to signal their readiness to shelve that if they are to get a deal on income tax.

However, big parties have rights too, as the first minister indicated with a gentle grin. The SNP may not have won a majority but their manifesto, tax package and all, did attract more support than the rival proposals.

Ideological dispute

Another point or two. Negotiations will now begin with all the opposition parties although, as indicated previously, the Greens appear to be the most probable buddies.

But the ideological dispute - as opposed to detailed discourse - is once again between the SNP and the Conservatives, enhancing somewhat the potential polarisation of Scottish politics which the other parties are, validly and understandably, eager to challenge.

It is the Tories who advocate relatively low taxation. To various degrees, the Scottish government and the other opposition parties are advocating the use of Holyrood's tax powers.

In this respect, one might note an apparent shift in the philosophical underpinning of the SNP's approach.

It is not so long since they were proposing a three per cent cut in corporation tax. That could be set alongside a council tax freeze, restraint on income tax and plans to cut aviation tax.

Ruth Davidson's Conservatives advocate relatively low taxation

Inasmuch as there was a grand design, as opposed to pragmatic use of limited available powers, that design involved stimulating the economy via lower taxation. There was talk of the Laffer curve.

Now, by contrast, the corporation tax objective has been shelved (setting aside the point that the power currently does not exist).

And Nicola Sturgeon argues that an increase in the overall income tax levy can be positive and productive for business - for example, through policies which directly support growth or indirectly enhance the workforce such as free tuition.

In her contribution, Ruth Davidson of the Tories contradicted that approach. However, it was notable that she did so with a minimum of invective and passion.

Plainly, the Tories have concluded that they must make their points in a tone which respects the alternative standpoint, rather than dismissing it bluntly from first principles.

But that ideological, philosophical division is real and it can be expected to play a larger role in Scottish politics. That, indeed, is one of the principal reasons why the first minister and Mr Mackay have chosen to set out options. To stimulate debate.

- Published2 November 2017