Brexit, borders and backstops

- Published

PM: Extension would be 'a matter of months'

The Prime Minister's customary demeanour is one of apprehension, as if she has just caught sight of a rather large autumnal spider in her peripheral vision and cannot quite dismiss arachnids from her thoughts.

So it is difficult to be certain. But she seemed to me to be enduring enhanced anguish in Brussels as she tried to explain the latest Brexit proposal, that there might be an extension of the transition period.

As if hearing the voices of her critics in her ears as she spoke, she attempted to mollify. Only an idea. Just a notion. Months, remember, not a year. Look, won't even happen. Probably.

And the impact of such vacillation? To make matters worse, of course - and to lessen her diminished authority in the by-going.

Why was such reassurance necessary? Because even the floating of the idea - that the extension might be for a year - had provoked another row in Westminster among backbench Tories? (Is there any other sort, given the frequency of resignation from ministerial office?)

No less a figure than Nadine Dorries had called for Mrs May to be replaced as PM. You must remember Ms Dorries. Called David Cameron and George Osborne "posh boys"? Went to the televised jungle as a celebrity apparently intent on getting out of there? That's the one.

Normally, of course, such an intervention would be dismissed by a serving PM, if it were even heeded at all. But it's not Nadine Dorries who worries Mrs May. It's those who come after and those who came before. It's the palpable evidence that she is not remotely in command of her party.

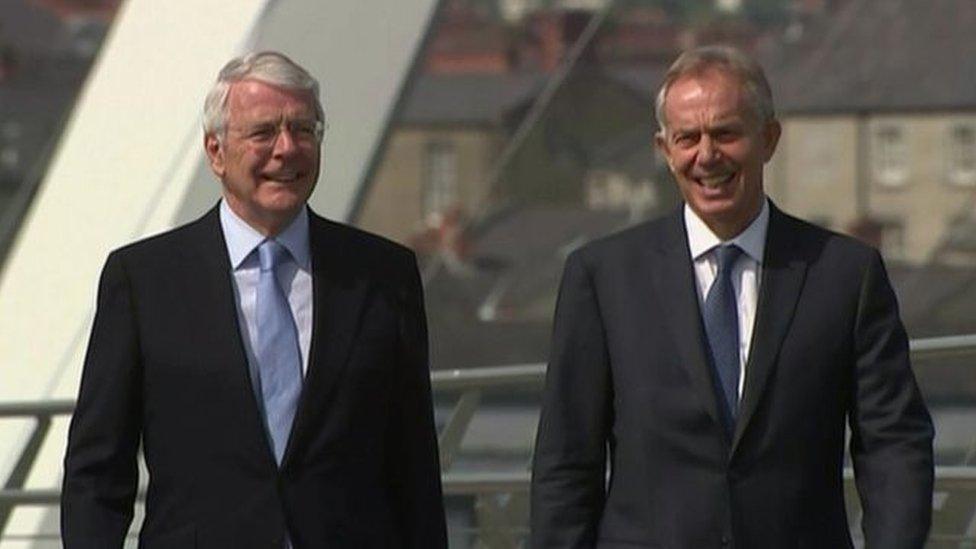

Former dispatch box foes John Major and Tony Blair find themselves on the same side over Brexit

Some may dismiss all this as internecine squabbling of a sort which commonly attends political machinations and decision-making. That is to miss the point.

To a large extent, this entire Brexit exercise owes its genesis to a fundamental fissure in the Conservative Party - and to the inability of successive leaders to close it down.

The other day, John Major intervened with substantive effect in the current controversy, warning that his fellow party members would never be forgotten or forgiven if they wreaked economic damage upon the UK in the fashion he anticipated.

Sir John Major knows about reputational damage and fading authority. In office for seven years as Prime Minister, he was persistently pursued by Euro-sceptics in his own party - and, eventually, by Tony Blair as the opposing Labour leader.

In the Commons - on the 25th of April 1995 - the then Mr Major attempted to turn the tide upon Mr Blair, reminding him that several Labour MPs had defied the front bench over the Maastricht treaty.

Rising slowly and assuming a sharply satirical air, Mr Blair noted that there was "one very big difference" between them.

Then he added, with smiling menace aimed directly at the PM: "I lead my party. He follows his." Much later, Mr Major wryly conceded it was the best one-liner he had faced.

David Cameron: Brexit's turned out 'less badly than we first thought'

But there is another "very big difference" to note. Sir John faced the same trials and tribulations over Europe as his eventual Conservative successor David Cameron.

Indeed, given that Mr Cameron initially led a coalition cabinet containing Europhile Liberal Democrats, it might be said that Mr Major faced the tougher immediate challenge inside his own team.

But, instead of conceding a referendum on the EU, Mr Major chose to stand down and defy one of his critics to stand against him for the party leadership. John Redwood obliged and lost.

It was, Mr Major recognised, a question of leadership. By contrast, Mr Cameron gave way and held a referendum which, against his expectations, resulted in a vote to leave the EU.

(Historians of the Labour Party will, of course, recall that, in 1975, Harold Wilson also called a referendum on the then common market. Reflecting internal divisions, Labour cabinet ministers campaigned for rival sides. Britain voted to remain.)

Back to the Tories. It should be added that Mr Cameron faced an external electoral threat in the shape of UKIP. That undoubtedly shaped and sharpened his thinking. Nevertheless, he actively conceded ground to the Euro-sceptics in his party. In terms of inherited authority, that ground has yet to be regained.

Mrs May knows the road ahead is a tricky one

Which leads us to Theresa May's fretful demeanour in Brussels. She knows that her control of events is decidedly limited, not least within her own party. Before resigning from cabinet, Boris Johnson made minimal effort to disguise his contempt for the strategy being pursued by the PM. Since leaving, even that faint patina of respect has vanished.

As I have repeatedly written, all political parties are coalitions of the more or less willing. From time to time, an issue arises which trumps the inherent impetus to stick together in the pursuit of power.

Such may now have arisen for the Conservatives. However, throughout history, they have shown a quite remarkable capacity to bind, even in the most challenging of circumstances.

It is possible that they may split - although it is difficult to envisage the regrouping that would then be required, which makes the prospect less likely.

Equally, it is feasible that a Brexit deal may be fudged, permitting the bulk of the party (with defiant outliers) to stay in line. It is then feasible, although currently hard to visualise, that the anguish of Brexit might diminish somewhat, allowing the Tories to coalesce again, roughly, around a free market economic programme and common loathing of Jeremy Corbyn.

But such a scenario will require leadership. In negotiation with EU leaders - who seem willing to bargain, but increasingly fed up of the prolongation of the process which deflects them from tackling the pressing concerns of the remaining 27 states.

It will require leadership in the Commons, where a confirmatory vote has to be achieved. And that will require leadership in the Conservative Party.

Sooner or later, Theresa May will have to summon authority if she is to have any chance of success. She knows it. That is why she looks so worried.

- Published18 October 2018