The five Alex Salmond row inquiries

- Published

MSPs are to hold an inquiry which may focus on meetings between Ms Sturgeon and Mr Salmond

Nicola Sturgeon and her government are facing multiple inquiries over the collapse of the investigation of former first minister Alex Salmond. How will these play out, and what might it all mean?

It's been quite a week.

Last Tuesday, in the courtroom where he was sworn in as first minister, Alex Salmond scored a legal victory over the government he once led when it was forced to concede that it had acted unlawfully while investigating sexual harassment complaints against him.

The row has since landed squarely on the doorstep of his successor, Nicola Sturgeon - literally, given the questions now being asked about meetings at her Glasgow home.

In the seven days since Mr Salmond walked triumphant from the Court of Session, FOUR new inquiries have been set up to find out exactly what happened.

An internal government study of failures in its own investigation.

A probe over whether Ms Sturgeon breached the ministerial code.

An Information Commissioner investigation of whether confidential information about the government investigation was leaked to the media.

A parliamentary inquiry potentially covering all of the above.

All of those are in addition to ongoing police investigations. That is the only inquiry looking at the substance of the complaints, which Mr Salmond robustly rejects.

Alex Salmond, with his cabinet, after securing majority government in the 2011 election

An easy question, first - how did we get here?

The short version is that two sexual harassment complaints were made to the government about Mr Salmond in January 2018, under a new complaints procedure drawn up by permanent secretary Leslie Evans, and signed off by Ms Sturgeon.

Mr Salmond - who denies any criminality at any time - said the process was unfair, and launched a judicial review of how the complaints were investigated.

He's also upset about how the whole matter became public - and to that end he has lodged a complaint with the Information Commissioner's Office about the apparent leak of the allegations to the press.

The government was initially up for contesting the judicial review. But days before the full hearing was meant to begin, it conceded that the investigating officer assigned to the inquiry had previously had some contact with the two women making the complaints, rendering the whole thing invalid.

It's important to stress that none of this tells us anything at all about the merit or otherwise of the complaints - a separate police probe is ongoing into those, which means everything has so far, and is going to continue, to focus squarely on process.

Alex Salmond: "While I am glad about the victory that has been achieved today I am sad it was necessary to take this action."

From day one, Mr Salmond was always clear that his issue was with Ms Evans, rather than his successor in Bute House. He was keen to make this point repeatedly outside the court, calling on her to consider her position over the government's "abject humiliation".

An internal review is now examining exactly how said humiliation came about, and who is responsible. Shouldn't someone have noticed that the investigating officer had previously been in touch with both of the women making complaints, when the newly-minted rulebook expressly forbade this?

The government's lawyers were keen to stress in court that the officer - a "dedicated HR professional" - would not be "held up as a sacrifice".

So does that mean Ms Evans ultimately carries the can? Mr Salmond certainly thinks so.

But as keen as he is to stress that he doesn't blame the first minister for the "botched mess" of a process, it is notable that Ms Sturgeon has placed herself squarely behind Ms Evans and that process - which, after all, she personally signed off.

Ministerial code

At Holyrood, Ms Sturgeon was quickly drawn into the row, after telling MSPs that she had discussed the inquiry with Mr Salmond on five separate occasions while it was still ongoing.

After a couple of bruising Holyrood sessions where she was fairly peppered with questions by opposition leaders, the first minister referred herself to the independent advisers on the Scottish ministerial code, which Labour claim she has breached.

And that wasn't the end of it - within days, a full parliamentary inquiry into the debacle had been confirmed, which unlike the code probe will take place in public.

Ms Sturgeon insists she conducted herself appropriately throughout the matter. She may now be tasked with explaining this again and again in front of a whole series of inquiries.

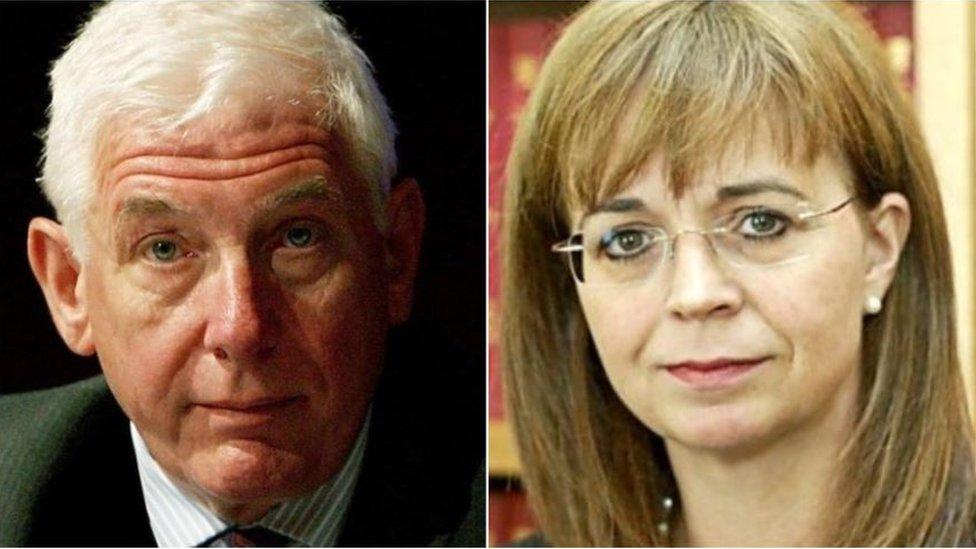

James Hamilton and Dame Elish Angiolini are the current independent advisers on the ministerial code

So, what's the deal with the ministerial code and those independent advisers?

The idea of having such a system dates back to 2008, when an expert panel - initially comprising two former Holyrood presiding officers George Reid and David Steel - was appointed to adjudicate on complaints of ministerial wrongdoing.

Currently, the independent advisers are a former Lord Advocate, Dame Elish Angiolini QC, and James Hamilton, a former director of public prosecutions in Ireland. Either one or both could be called on for this case.

Ms Sturgeon has never faced an inquiry like this before, but Mr Salmond was all too used to them when he was first minister. He was referred to the advisers on six occasions, but was never found to have breached the code.

These included several claims he had misled parliament during exchanges at weekly questions, complaints about him feting SNP party donors as first minister, and a row over legal advice about Scotland's potential membership of the European Union in the event of independence.

What we can learn from these quite separate cases is that they take place behind closed doors, are quite tightly drawn in remit, and tend to last about three months from referral to report.

Scottish government chief of staff Liz Lloyd, pictured here with Ms Sturgeon in 2015, was present when the first minister met Alex Salmond in April 2018

This inquiry looks set to focus primarily on a meeting between Ms Sturgeon and Mr Salmond at her home in Glasgow on 2 April, 2018.

This was the meeting where Ms Sturgeon says she was told about the complaints against Mr Salmond for the first time. It was arranged via talks between her chief of staff, Liz Lloyd, and Mr Salmond's old chief of staff, Geoff Aberdein.

Mr Aberdein says, external himself and Ms Lloyd (and former SNP MSP Duncan Hamilton, a lawyer who later worked on Mr Salmond's judicial review) were all in the house for the meeting - but weren't "party to the conversation between Nicola and Alex".

This brings us to the ministerial code, external, which states that "a private secretary or official should be present for all discussions relating to government business", and "the basic facts" of such meetings should be "recorded".

The section of the code quoted by Labour in their complaint states that if ministers "find themselves discussing official business without an official present - for example at a party conference, social occasion on holiday - any significant content should be passed back to their private offices as soon as possible after the event, who should arrange for the basic facts of such meetings to be recorded".

Geoff Aberdein was at Alex Salmond's side after the SNP won a majority at the 2011 Holyrood election

The first question that needs to be answered - and which might preclude many others - is whether the meetings between Ms Sturgeon and Mr Salmond constitute "discussions relating to government business".

Ms Sturgeon insists that her discussions with her predecessor were strictly SNP business, between a party member and his leader.

Opposition MSPs protest that they were talks between the leader of the government and a former leader of the government, facilitated by a government official, about a government investigation into complaints by government staff.

If they weren't "government business", then it doesn't seem like there could have been any breach.

Recorded meetings

If they were, then that leads on to fresh questions - were any officials present? Ms Lloyd was seemingly in the house for the first meeting, but Mr Aberdein says she wasn't "party" to the talks.

Next, were "the basic facts" of these meetings recorded?

Ms Sturgeon flagged up the fact that she was aware of the investigation prior to the second meeting, on 7 June, and subsequent communications were all flagged up to officials. But what record is there of the meeting and the phone call that took place before that?

This is what the independent advisers will be pondering.

Here's one question we can answer, at least - if the advisers do decide there has been a breach, what might that mean?

Looking back at the ministerial code, it underlines that "the first minister is the ultimate judge of the standards of behaviour expected of a minister and of the appropriate consequences of a breach of those standards".

So the matter will remain largely in Ms Sturgeon's hands, as damaging as any finding against her would be.

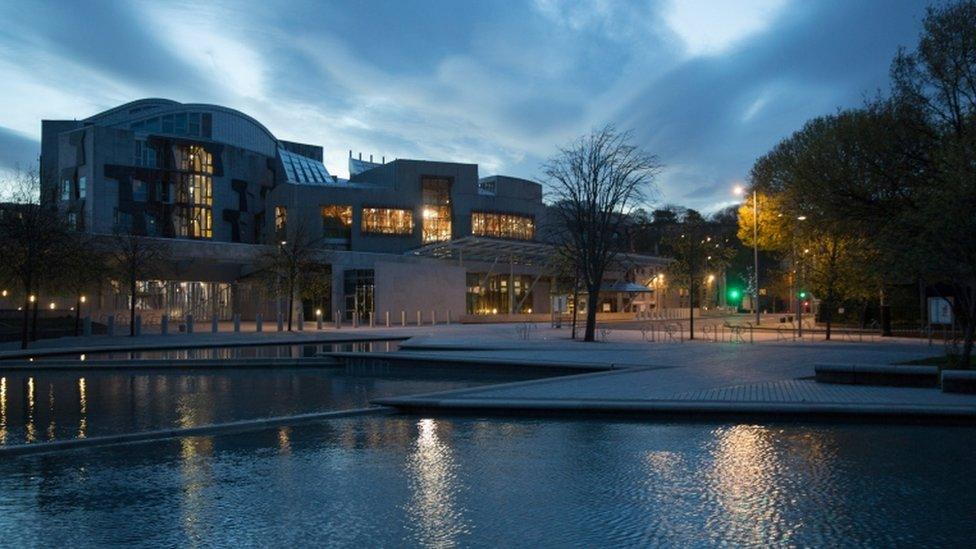

MSPs are to hold a Holyrood inquiry into what went wrong with the government's investigation

One thing that definitely won't be in the first minister's hands is the parliamentary inquiry.

We don't know much yet about what MSPs will look at, although some have voiced confidence that Ms Sturgeon's meetings will form part of the remit.

Parties have unanimously agreed that there should be an inquiry, at some point, and officials have gone away to think about how this would be structured.

Holyrood's role

A new committee would be set up - a question mark remains over who would be on it, and which party would get the chair - but not a huge amount else has been agreed. It might be some time before much is.

The Lib Dems in particular have stressed that "the police investigation must be the priority", saying that the complaints "deserve to be thoroughly investigated by the police without political interference".

It might be the case that parliament gets itself into position to hold an inquiry, but ultimately waits for the police investigation to run its course before taking any evidence.

If nothing else, that emphasises that this won't be sorted out quickly.

There are some other things going on in the country

One last question. How big of a deal is this?

To those outside the political bubble, it might all seem a bit procedural. With Westminster embroiled in the big Brexit conundrum and the Scottish government struggling to win support for its budget, is this really the burning issue of the day?

Little things matter

The problem is that in politics, it's often the little procedural things that get you.

Henry McLeish lost his job as first minister, external over a point of procedure about the sub-letting of his constituency office - saying on his way out that he didn't want it to be a distraction to the "real and pressing business" of government.

David McLetchie quit as Scottish Tory leader over taxi expenses, external. Wendy Alexander quit as Scottish Labour leader, external over an infringement on declaring donations which Holyrood's standards committee deemed worthy of a one-day ban from parliament.

All of these inquiries mean one thing, this is not an issue that's going to go away quickly. It's guaranteed to become a saga, dragged out over months rather than weeks.

Ms Sturgeon would far, far rather be talking about Brexit. Or the budget. Or, you know, the running of the country. Oh, and she's promised an update on a fresh Scottish independence referendum in the near future.

Having this issue hanging around - an open question about her government's competence and her involvement in the debacle - is worse than a distraction. It's an open wound which her opponents won't hesitate to press into each and every time they want to inflict pain on her government.