Tory leadership: Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt on Scotland

- Published

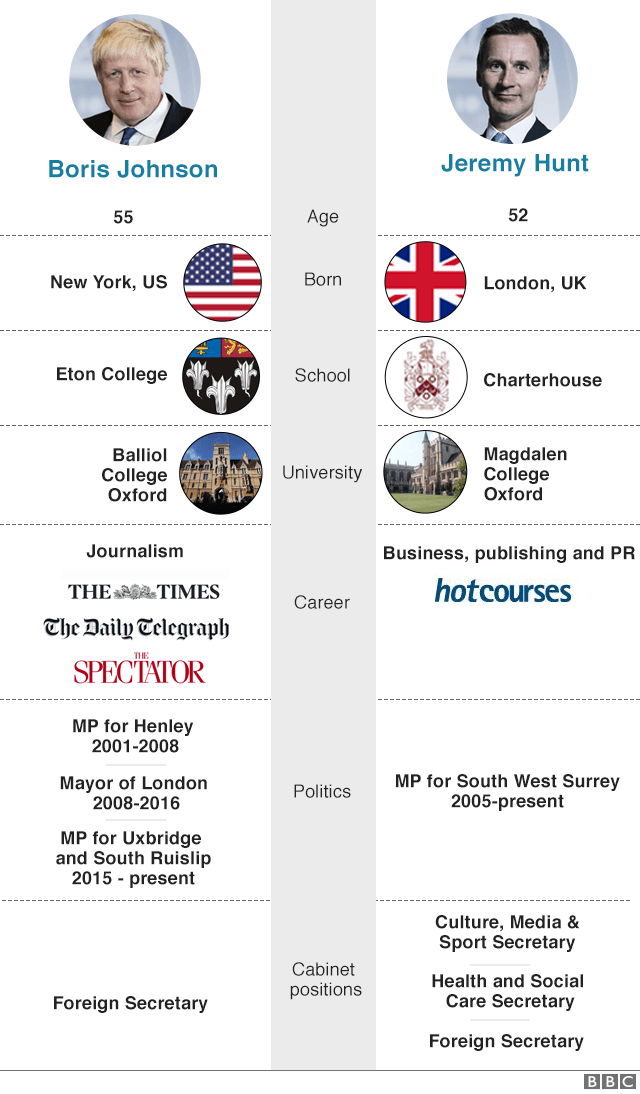

The Conservative leadership contest has come down to Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt

There are two men left in the Conservative leadership race, and within weeks one of them will be in Downing Street. What are the prospects for Scotland under Prime Minister Boris Johnson, or Prime Minister Jeremy Hunt?

Who's backing who?

Both men have ticked the most basic box of the leadership race by visiting Scotland and being pictured drinking Irn Bru - and have been rewarded with the backing of some Scottish Conservative MPs.

In the final round of voting by Tory MPs, Mr Johnson had the support of four Scottish members - Andrew Bowie, Douglas Ross, Colin Clark and Ross Thomson - to just one for Mr Hunt, in John Lamont.

Mr Lamont was one of eight MPs to nominate Mr Hunt at the start of the campaign, praising his "pragmatic approach and background in business", while Mr Thomson has been a longtime backer of Mr Johnson, calling him "fair, tolerant and compassionate".

The bulk of the Scottish Conservative group originally threw their backing behind Michael Gove - who also won the endorsement of Scottish party leader Ruth Davidson after her original choice, Sajid Javid, was knocked out of the contest.

Ms Davidson has now lent her support to Mr Hunt, although she concedes that this might be "the kiss of death" for the foreign secretary.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, meanwhile, has attacked both candidates, saying they are "out of touch with mainstream opinion in Scotland".

She also backed the position of her party's leader at Westminster, Ian Blackford, who branded Mr Johnson a "racist".

Brexit and indyref2

Jeremy Hunt has pledged himself to the UK union "with every drop of blood in my veins"

Even going back to when there were a dozen of them, all of the Tory leadership candidates have placed themselves firmly against a second Scottish independence referendum - something Ms Sturgeon wants to see happen in the second half of 2020.

Some earlier candidates like Sajid Javid and Esther McVey were criticised for taking the hardest line and saying they would not "allow" a referendum to be held.

And while others have been slightly more nuanced at least in their language, Mr Hunt was actually the first member of the cabinet to rule out Nicola Sturgeon's most recent bid for a referendum, back in March 2019.

He doubled down on those comments during a recent visit to Aberdeenshire, telling reporters that he "passionately" supports the UK union "with every drop of blood in my veins".

Mr Hunt - who described himself as "the prime minister Nicola Sturgeon does not want" - said he would "never allow the union to be broken up". He even put this ahead of Brexit in his priorities, saying: "I would never pay any price if it meant that Scotland would become independent."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

This followed a YouGov survey of Tory members which suggested a majority would accept the break-up of the UK in exchange for Brexit, and a Sunday Times poll which suggested a majority of Scots could back independence if Mr Johnson became prime minister.

With Scotland having voted by 62% for Remain in the 2016 referendum against the UK's overall vote to leave, Ms Sturgeon has put the divergence over Brexit at the heart of her case for a new independence ballot - particularly the prospect of a no-deal exit.

On that front, Mr Johnson has pledged to leave the EU without a deal on 31 October, the current deadline, if no agreement can be reached. Mr Hunt says he is also prepared to leave without a deal - but has not ruled out a further extension to the deadline if an accord is in sight.

In any case, Mr Johnson has also nailed his colours to the mast of the UK union, tweeting that "the United Kingdom truly is better together and we must never put that at risk", so it seems unlikely that he would readily sign up to "indyref2".

And he has claimed that Brexit "done right" could actually "cement and intensify" the UK union, saying: "If you Brexit sensibly and effectively, you take away so much of the ammunition of the SNP."

Although Ms Sturgeon has not yet formally requested support for a new independence vote - she says she's waiting to negotiate with whoever wins - she has said it would be "undemocratic" and "unsustainable" for the current refusals to continue.

Policy pledges

Boris Johnson's tax plans could have consequences north of the border

Policy plans have been fairly thin on the ground so far in the campaign, and the fact that many key areas are devolved to Holyrood blunts the impact of many domestic pledges north of the border.

For example, both men have made promises about funding for education, which would not specifically apply in Scotland as education policy here is set at Holyrood.

Although Scottish ministers get a proportional share of any extra funds allocated to devolved policy areas - "Barnett consequentials" - they can spend that cash however they please.

However, one early pledge has caught the eye despite technically not applying north of the border - Mr Johnson's plan to give a tax break to higher earners.

His proposal is to raise the higher rate threshold (HRT) of income tax from £50,000 to £80,000. This would not apply in Scotland, and given the Scottish government has already broken with the UK system by holding the Scottish HRT at £43,430 (as well as raising the rate itself by a penny), they presumably would not follow suit.

The wrinkle is that Mr Johnson's giveaway would be funded in part by National Insurance Contributions (NICs), which are not devolved.

NICs have a sort of threshold of their own, dropping from 12% to 2% at the "upper earnings limit" (UEL), currently matched to the UK HRT. Basically when your income tax goes up, your NICs go down, cushioning the blow.

Income tax is devolved to Holyrood - but National Insurance Contributions are not

A gap has developed in the system where Scots who have earnings in the range between the Scottish and UK HRTs - currently those between £43,430 and £50,000 - pay the higher rates of both income tax and National Insurance. This tots up to an overall (or "marginal") tax rate of 53%.

So because Mr Johnson's plans would also raise the UEL - perhaps as high as £80,000, although he hasn't been entirely clear about that - high-earning Scots would see an even bigger chunk of their earnings taxed at this high marginal rate. Without benefiting from the income tax break.

The Chartered Institute of Taxation calculates that if the UEL rises in line with the UK HRT, Scots earning more than £80,000 would end up paying £7,844 more per year in tax than someone on the same salary elsewhere in the UK - a major increase on the current tax gap, which stands at about £1,500.

All of that said, one of the beneficiaries of this move could be the Scottish government.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies, external points out that the "fiscal framework" agreement which underpins devolved finances makes clear that Scotland should not lose out as a result of any tax decisions taken at Westminster.

So when income tax revenues are cut at Westminster, Holyrood is compensated with increased funding in its annual block grant.

That means the Scottish government would actually get a budget boost as a result of an rUK tax cut - albeit at the expense of those aforementioned higher earners, who on past form are unlikely to get the money back again via a devolved tax break.

- Published18 July 2019

- Published21 June 2019