General election 2019: Deals, pacts and tactics in Scotland

- Published

- comments

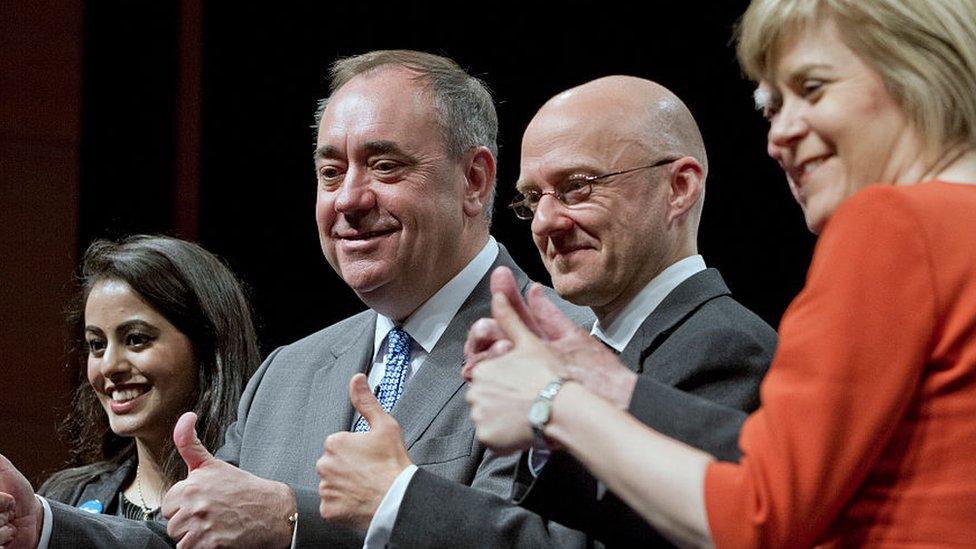

The 'remain alliance' at Holyrood in 2016 included pretty much everyone - but there seem to be few cross-party agreements now

Electoral pacts have formed along both pro and anti-Brexit lines elsewhere in the UK, but there is little evidence of them in Scotland. With thin political margins and very few truly "safe seats", why aren't these deals happening north of the border?

Conservatives and the Brexit Party

The Brexit Party had initially claimed they would stand in 600 seats across the country, but then announced with great fanfare that they will not contest any Tory-held seats so as not to split the pro-Leave vote.

This has already proved controversial within the party north of the border, with MEP Louis Stedman-Bryce stepping down as a general election candidate in protest at the move.

The impact of the deal in Scotland is likely to be fairly minimal, given there was no UKIP or other pro-Leave party presence in any of the 13 seats the Tories won in 2017.

And as with elsewhere, the presence of Brexit Party candidates could have a real impact in seats the Conservative are targeting, rather than defending. After all if Boris Johnson wants a majority, he needs to gain seats, not just hold onto the ones he has.

For example, at the time of writing the party is planning on putting forward a candidate in Perth and North Perthshire, a seat the Tories failed to take from the SNP by just 21 votes in 2017.

Given the Brexit Party finished second in the European elections in Scotland in May while the Conservatives slipped to fourth, there is a real prospect of them picking up some votes from local Leavers - making the Tory task in trying to gain the seat all the harder.

Remain Alliances

The Lib Dems, Greens and Plaid Cymru have formed a "remain alliance" in other parts of the UK - but not in Scotland

The Lib Dems, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party of England and Wales have entered into a "remain alliance" in dozens of seats across England and Wales, agreeing not to stand against each other so as not to split the anti-Brexit vote.

But in Scotland, no such pact exists. All of Holyrood's parties backed Remain in the 2016 referendum with only a handful of MSPs voting the other way, so the pro-EU field is too crowded for anyone to carve out an alliance.

Indeed the competition for Remainer votes is fierce, particularly between the two most outspokenly Europhile parties - the SNP and the Lib Dems.

This extends beyond the fact the pair contest the tightest marginal in the entire country - North East Fife, SNP majority of two votes - while the SNP are the closest challengers in all four current Scottish Lib Dem seats.

If you look at the 13 seats the Scottish Tories won in 2017, the SNP were in second place in all of them, while the Lib Dems were fourth (or to put it another way, last).

So, while the SNP would dearly love to pick up pro-EU Liberal votes in these and other marginal seats, there are none where they would want to stand aside for the Lib Dems as a quid pro quo. It takes two to tango, and in terms of realistic contests this would essentially have to be a one-way deal.

There is also an unbridgeable ideological divide between the two on the topic of Scottish independence, a live issue in this campaign.

Instead of an alliance, there is a real and occasionally bitter contest between the two. This is perhaps best illustrated by the fact each has targeted knocking off the other's leading figures, with the Lib Dems going after Ian Blackford in Ross, Skye and Lochaber and the SNP hoping to take East Dunbartonshire back from Jo Swinson.

SNP and the Greens

The Greens and the SNP were on the same side in the 2014 independence referendum, but are not entering into any electoral pacts

The Scottish Greens were a non-factor in the 2017 elections, standing just three candidates. This came as a bit of a relief to the SNP, who seem to consider themselves the most likely second home for the party's pro-independence, pro-European, climate-concerned voters.

Indeed that year there were five seats where the SNP ultimately won by fewer votes than the Greens had polled locally in 2015. Who knows where those former Green votes actually went - maybe they just stayed at home - but it's entirely possible that they proved decisive.

So, the fact the Greens have announced their intention to run in more than 20 seats this time round is potentially a big deal.

They have been very clear that they won't be entering into any alliances, be they pro-EU or pro-independence. They chiefly have an eye on the 2021 Holyrood elections, wanting to make sure they are clearly differentiated from the SNP despite the similarity on key issues.

However, the places they have chosen to stand and also not to stand are significant.

The party had initially suggested it would contest Perth and North Perthshire, drawing a furious response online, external from SNP incumbent Pete Wishart (he held off the Conservatives by just 21 votes). He had warned that the Greens could be responsible for a Conservative gain there.

But the local party branch has now decided not to put forward a candidate (a move hailed by a "really grateful" Mr Wishart), as has the one for North East Fife, another key marginal.

The Greens are still standing in a handful of fairly tight SNP defences, but the biggest potential impact for a split pro-independence vote might end up being in seats the SNP are targeting - like the 0.3% Tory majority in Stirling, or the 0.6% Labour lead in Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath.

SNP and Labour

Nicola Sturgeon's SNP could back a Jeremy Corbyn government on an "issue by issue basis" - but would not go into coalition

You might hear a lot about this supposed "deal", but there has been no formal agreement between the SNP and Labour about what might happen if there is a hung parliament.

Nicola Sturgeon has been clear (for the third election in a row) that she would not enter a formal coalition with anyone, but could potentially prop up a Jeremy Corbyn government "on an issue by issue basis".

One of those issues would undoubtedly be independence, with Ms Sturgeon telling Mr Corbyn not to bother even asking for SNP votes unless he accepts the "principle" of a new independence poll.

All of that said, don't expect the SNP and Labour's Scottish candidates to give any ground to each other on the campaign trail. There are 28 seats in Scotland which are SNP-Labour marginals (seats with majorities under 10%), and ten of them could be decided by a 1% swing.

Labour's message is sure to be "vote Labour", even if SNP MPs do end up being useful in putting Mr Corbyn in Downing Street as Scottish Labour ones.

The Tories are playing up the possibility of an SNP-Labour deal in their campaigning - south of the border in particular - but such a thing will not materialise until after the election, and even then only if there is a hung parliament.

Until such a scenario comes to pass, expect the SNP and Labour to continue to fight like cats in a sack.

Pro-union pacts?

There will be no 2014-style pact between the pro-union parties in Scotland, but might they tacitly encourage tactical voting in some areas?

The flip side of the SNP-Green pro-independence coin is the potential for collaboration between the Scottish parties which are opposed to independence.

This was noticeable in some of the results from the 2017 elections, where a few high-profile scalps seemed to result from votes shifting between the unionist parties.

Take for example Gordon, where former First Minister Alex Salmond was toppled by a 30-point Tory surge. The SNP vote slipped badly, by 11 percentage points, but it was the local Lib Dems who really disappeared, down by 21 points. It's hard not to conclude that local Liberals voted Tory in a bid to unseat Mr Salmond.

Whether that happens again in 2017 is more of a question - will habitual Lib Dem voters be as tempted to vote for the Conservative Party of Boris "Brexit do or die" Johnson?

Nicola Sturgeon actually raised the issue at first minister's questions, citing newspaper reports that Labour and the Tories might give the Lib Dems a (relatively) free run at Mr Blackford in Ross, Skye and Lochaber. Slamming the "Better Together" parties always plays well for the SNP and helps Ms Sturgeon motivate her party's base to get out and vote, but this kind of talk clearly does cut through with some.

A plainly false post briefly went viral on social media claiming that the Conservatives weren't going to stand against Lib Dem leader Jo Swinson in East Dunbartonshire, to make sure the SNP wouldn't retake the seat.

To be clear, the Tories, Labour and the Lib Dems will contest all 59 seats as usual.

But how hard they will actually campaign in different areas is more of a question. Resources are always going to be directed towards the most winnable seats, and areas where another party is the most likely challenger to the SNP will not be high priorities.

- Published12 November 2019

- Published7 November 2019