Scottish independence: Could the Supreme Court rule on a referendum?

- Published

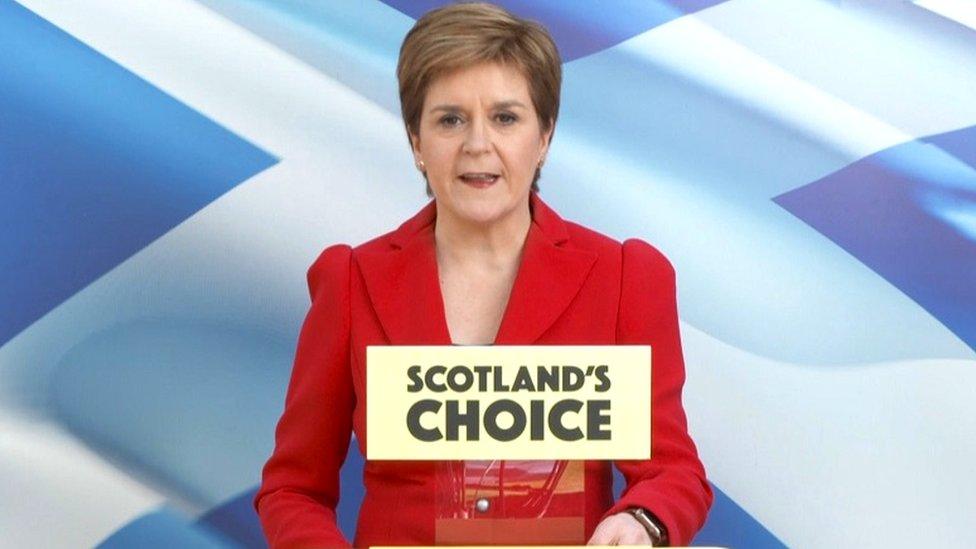

Nicola Sturgeon's requests for a referendum agreement have so far been stonewalled by Downing Street

Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon wants there to be a fresh referendum on Scottish independence - but Prime Minister Boris Johnson does not.

The two governments may end up taking their arguments to the Supreme Court - but why? Would this really settle the issue?

We examine the constitutional standoff between the Scottish and UK governments.

What's going on?

The SNP has just won an unprecedented fourth term in office in the Scottish Parliament election, winning more than twice as many seats as their nearest rivals.

They stood on a manifesto to hold a second independence referendum in the coming years - as did the Scottish Greens. Between them the two parties have a clear pro-independence majority at Holyrood.

However, this does not mean they can go straight ahead to planning a vote.

For Scotland to actually become independent, Ms Sturgeon is clear that the process must be both legally and internationally recognised.

And Mr Johnson is clear that he does not want there to be a referendum any time soon, saying the vote in 2014 - which saw Scots reject independence by 55% to 45% - should be binding for "a generation".

The referendum in 2014 saw Scotland reject independence by 55% to 45%

Why would this end up in court?

Various laws need to be passed in order to set up a referendum - and there is not a firm agreement on whether MSPs have the power, under the current devolution settlement, to do this without the backing of UK ministers.

The previous referendum in 2014 was underpinned by an agreement between the Scottish and UK governments to formally transfer powers to Holyrood. This meant MSPs could legislate for a referendum without any wrangling over who actually had the powers in the first place - everyone was signed up to the process.

Ms Sturgeon wants to follow this "gold standard" approach for a new referendum - but has seen her requests for a similar deal shot down first by Theresa May and then by Mr Johnson.

The SNP leader insists the prime minister's position is unsustainable, and that he must back down.

If he does not, her plan to break the deadlock is to skip the agreement and just pass a referendum bill at Holyrood - and dare the UK government to challenge the legislation in court.

What is the procedure?

Once a bill has been approved by a final vote of MSPs, there is a four-week wait before it gets Royal Assent and becomes law.

During that period, anyone can come forward with a challenge to the legitimacy of the legislation. So if the UK government believed MSPs were acting beyond Holyrood's powers, they could have law officers issue a challenge and argue the toss in the Supreme Court.

This has happened before, over Brexit legislation - and there is currently a standing challenge to two other Holyrood bills.

Once a challenge has been made, the bill effectively goes on ice until judges at the Supreme Court have ruled on whether it falls within the set of powers devolved from Westminster to Holyrood.

If judges raise particular concerns about parts of the legislation, it can be sent back to Holyrood to be amended - or if there are fundamental issues, it can simply go in the bin.

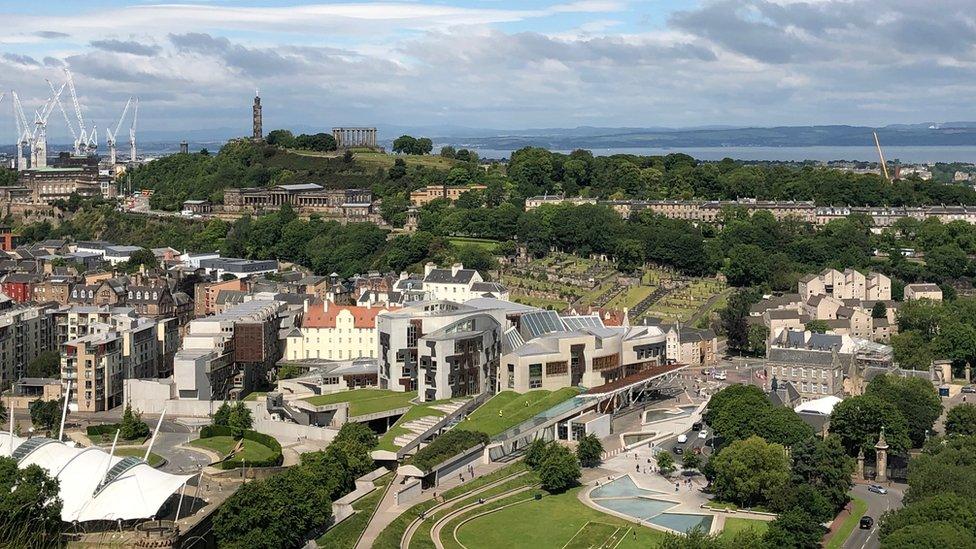

There is an open legal question as to whether MSPs in Edinburgh could legislate for a referendum on their own

What would judges be deciding on?

The Scotland Act lists "aspects of the constitution" and specifically "the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England" as reserved matters - and says MSPs are not allowed to legislate on anything which "relates to reserved matters".

For UK ministers, this makes it very clear that the matter of the union is reserved to Westminster - and thus MSPs cannot legislate for an independence referendum without straying beyond devolved powers.

However, there is a school of argument that the bare fact of holding a referendum about the union would not necessarily impact on the union directly.

It would effectively be advisory, an illustration of the will of the people, and a mandate for independence negotiations to begin - like the Brexit referendum sparked years of negotiations, rather than drop the UK out of the EU on the spot.

This argument accepts that Scotland could not break up the union unilaterally - but holds that the act of holding a referendum would not necessarily be an act of secession in itself, rather a possible prelude to one.

So the question judges would likely be answering is whether or not the holding of a referendum directly "relates to" the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England.

All of that said, we do not know precisely on what terms any court challenge would be fought - there may be many more arguments which could be put forward by either side.

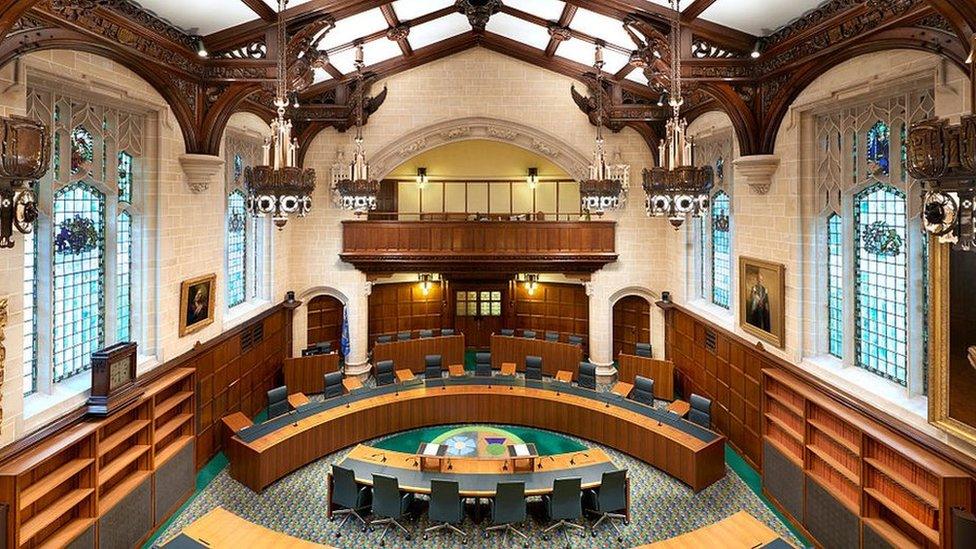

Supreme Court judges are called upon to decide weighty matters of constitutional law

Has this been tested in court before?

Not directly, but there have been two cases which may be of relevance.

The first was a challenge brought to the Court of Session by independence campaigner Martin Keatings, who advanced similar arguments to those noted above.

The court declined to take a view, saying that a citizen-led challenge was "premature, hypothetical and academic" and that the proper approach would be a challenge in the Supreme Court.

Lord Carloway - Scotland's most senior judge - did drop a hint that "it may not be too difficult to arrive at a conclusion" when the case does ultimately come up, although it would likely be fought in a different court and potentially on different arguments.

The other case was the UK government's successful Supreme Court challenge to Holyrood's Brexit legislation in 2018.

MSPs had passed their own alternative to Westminster's EU Withdrawal Act, but judges said parts of it could not be allowed to stand - in part because of changes UK ministers made to their own legislation late in the day.

They added the Withdrawal Act to a schedule of protected legislation which the Scotland Act says MSPs cannot modify - rendering much of the Holyrood bill beyond competence. The Scottish government were furious, saying the goalposts had been moved midway through the match.

There has been a suggestion that should UK ministers fear defeat in the Supreme Court over legislation for a referendum, they could take the same approach again.

That might be a killer move from a legal perspective - but it might also be a dangerous one politically, if it was seen as a stitch-up by voters north of the border.

Would a court ruling settle the matter?

Legally, perhaps - but not necessarily politically. All of this is really a matter of process, rather than of the substance of the issue.

Say the court ruled that MSPs could legislate for a referendum.

It would undermine Mr Johnson's position in the court of public opinion, but there would still be nothing to stop him arguing against a referendum for one political reason or another - or indeed of the unionist side boycotting any poll set up in the absence of an explicit agreement.

This would still be a major consideration for Ms Sturgeon. It is not really the referendum she is interested in, but the result.

She wants the vote to be unimpeachable in its legitimacy, and to have international recognition - particularly from the EU - so that it can actually deliver independence.

A victory in court would be great news for her, and potentially a useful tool in forcing Downing Street's hand - but the victory she craves is a political one. She needs both sides to be willing participants, signing up to a contest on a level playing field.

The same would be true if the court ruled that the process of setting up a referendum fell outside Holyrood's competence. It would not make the issue of Scottish independence simply disappear.

Ms Sturgeon would still point to a pro-independence majority in the Scottish Parliament and a series of polls suggesting Scots are divided on the issue. A legal ruling about process would not ruin the case for deciding this issue once and for all.

In short, Ms Sturgeon will still be out to secure an agreement with Downing Street either way.

- Published9 May 2021

- Published9 May 2021