Could Scots be guaranteed a minimum income?

- Published

The Scottish government is to start work on plans for a "minimum income guarantee" aimed at reducing poverty and inequality.

Social Justice Secretary Shona Robison is to chair a cross-party steering group to push forward proposals for the "innovative, bold and radical" policy.

How would the plans work, how much could it cost, and when is it likely to be delivered?

What is it?

A Minimum Income Guarantee (MIG) would aim to provide everyone in Scotland with a minimum acceptable standard of living - so that everyone has enough money for housing, food and essentials as well as covering individual circumstances like disability or caring requirements.

Studies were actually run during the previous Holyrood term of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) - a sweeping scheme which would see cash paid out to everyone, regardless of income or wealth. Proponents say this could cut poverty and welfare bureaucracy - but it would be expensive, and require buy-in from both the Scottish and UK governments.

An MIG differs from a UBI in important ways. Crucially, it is targeted at those on lower incomes, rather than being universal.

It would be paid out via a variety of sources, including tax reliefs, social security benefits and services in kind, like childcare and transport.

Ms Robison said such a scheme would be "revolutionary in our fight against poverty", but would not replace secure employment or keep wages down.

Proponents say a minimum income scheme could effectively wipe out working-age and child poverty

How much could be paid out?

It is still early days, so the Scottish government has not yet come up with detailed proposals or precise figures.

However, there are a lot of clues in a report from the Institute for Public Policy Research in Scotland (IPPR), published in March. Russell Gunson, director of the institute and co-author of the report, is co-chair of the government's steering group.

The IPPR suggested a "core entitlement" of £792 for a single person of working age per month, or £1,224 for a couple, with a further payment of £267 for the first child in a household and £224 for each additional child. These figures would "taper off" if an adult in the household was in work.

However, the exact figures could fluctuate based on the cost of things like food and housing. For example, if rents were to go up substantially, the housing payment part of the MIG would need to rise as well.

One of the key challenges in working out an MIG scheme would be calculating what constitutes a minimum acceptable income in any given time or place.

How do you work out exactly how much money people need to live?

What could it cost?

The stumbling block to universal income proposals is often cost.

The IPPR report concedes a scheme at the levels suggested would undoubtedly be "expensive", costing £7bn per year once up and running.

For comparison, all of the benefits administered by Social Security Scotland currently add up to about £4bn, and the Scottish government's annual budget is usually around £35bn.

In return for this massive investment, an estimated 2.5m people in Scotland would benefit - with the authors saying the MIG would "effectively eradicate working-age and child poverty".

But still, MSPs would likely need to raise significant new funds in order to pay for it, if they were to avoid making cuts elsewhere.

The authors of the IPPR report suggested increasing income tax rates or lowering the threshold of higher rates, raising more from council tax or introducing a new property value tax.

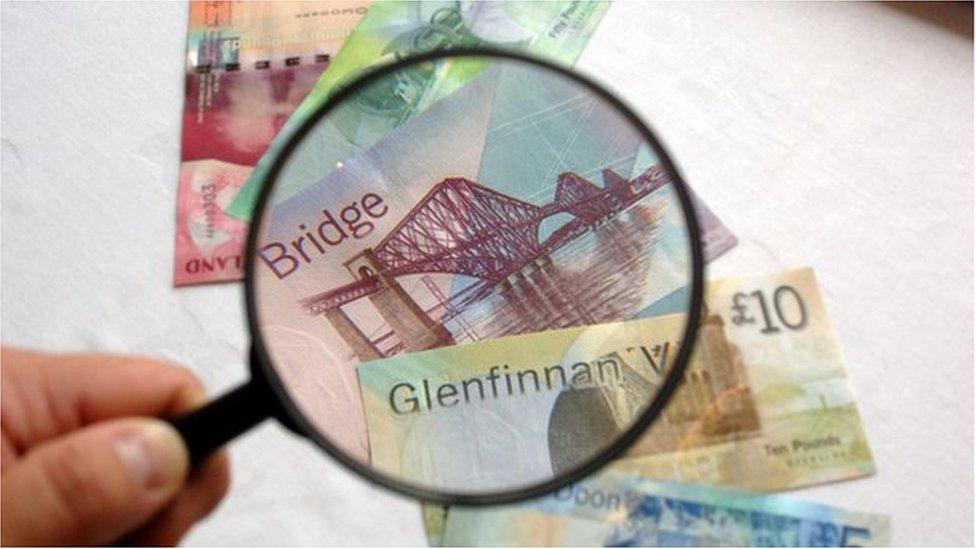

More money may need to be raised to pay for ambitious new schemes

When might this happen?

It is not clear how far the plans will progress in the immediacy.

The initial consultation is only due to run for one month, and MSPs from across the political spectrum have already been signed up to a "strategy group".

However, the SNP manifesto, external only committed to "start work" on the scheme during the current five-year parliamentary term, adding that it "cannot be done overnight".

There are, after all, some other pressing financial questions - like the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, the IPPR report targets having an MIG in place by 2030 - so towards the end of the next parliamentary term.

Given the SNP would hope to have at least held an independence referendum during the intervening years, it is unclear if these plans will be top priority - or if they could change substantially in line with the facts on the ground.

Related topics

- Published9 June 2020