Can Labour find a way back in Scotland?

- Published

Leading Labour - Keir Starmer and Anas Sarwar

Labour is attempting to lay the foundations for a political fightback at its party conference in Brighton, after a decade in opposition at Westminster and its worst Holyrood election result.

Leaders Keir Starmer and Anas Sarwar share a goal of marching their party out of the political wilderness, but also face a similar set of challenges and questions.

How can Labour turn its electoral fortunes around? Does it need Scottish seats to win at Westminster? And fundamentally, what is the party's role north of the border, as a third wheel in an increasingly binary set of debates?

Decline and fall

Things looked very different for Scottish Labour at the turn of the century. After Tony Blair's landslide ushered in the devolution era and Donald Dewar swept into the new parliament as Scotland's first first minister, the party was comfortably dominant and masters of its own fate.

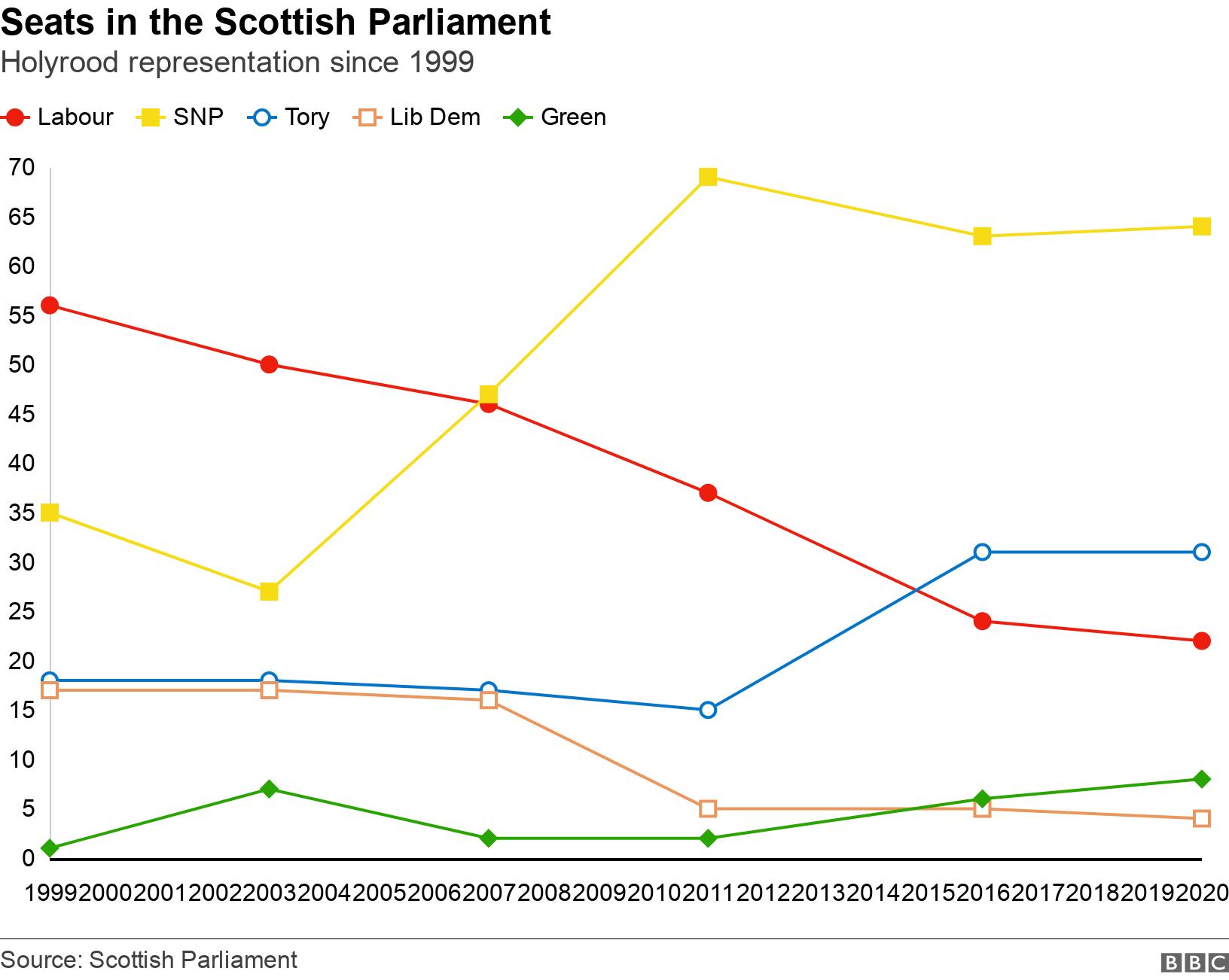

Since then, the story has been one of decline. At Holyrood it has been a steady slide; the party has lost seats at every Scottish parliament election, going from leading the government with 56 MSPs in 1999 to third place with 22 seats today.

At Westminster, the collapse was much more precipitous - Labour lost 40 seats in the immediate aftermath of the 2014 independence referendum. Having dominated north of the border throughout the second half of the 20th Century, the party is left clinging to a single Scottish constituency.

Things are no better at a local level. In 2017's council elections, Labour's share of the vote slid from 31% to 20%, on the way to third place behind the Tories and the loss of 133 seats.

And in the European Parliament elections of 2019 the party slumped to fifth place, with less than 10% of the vote - losing both of its seats.

When one is flat on one's back, the only way to look is up - but if there is a road back to the summit for Scottish Labour, it could be a long and winding one.

Fates intertwined

UK leader Keir Starmer has attempted to head off talk of party splits by declaring that winning is more important than unity.

But when it comes to success in Scotland, the two may still need to go hand in hand.

The party is locked in a circular paradox. In order to revive its fortunes in Scotland, it needs to look like a government-in-waiting at Westminster. But in order to look like a government-in-waiting at Westminster, it needs to revive its fortunes in Scotland.

The SNP would contend that given their MPs are unlikely to prop up a Conservative administration, Labour doesn't actually need Scottish seats to form a government. Of course, they would say that - they have no interest in letting a rival get back in the game, just as Labour has no interest in relying on SNP votes.

In theory, Mr Starmer could scrape together a majority without Scottish representation. But this would require him to gain seats in other parts of the country where Labour has never made significant inroads, in true blue Tory territory. It makes far more sense to target Scottish seats, like the one which provided the last Labour prime minister.

This is why within UK Labour circles, there is an acknowledgement that Scotland could well be pivotal.

But it means the party needs to be as convincing at a Scottish level as it is at a UK one - Anas Sarwar and Keir Starmer both need to succeed if either is to have a future.

Anas Sarwar and Keir Starmer are both fairly new to their roles - and are both on a mission to reconnect with the electorate

Leadership

Nicola Sturgeon has already seen off a succession of Scottish Labour leaders in her seven years as first minister. While dispatching Jim Murphy, Kezia Dugdale and Richard Leonard, she has encamped the SNP firmly on Labour's old turf - both at the centre-left of politics and in former heartlands like Glasgow, Dundee and Fife.

So has the party finally struck on the right man for the job in Anas Sarwar?

He will be heartened by the fact favourability polls, external suggest, external he is one of the more popular party leaders in Scotland, a country where the voting public apparently tend to frown on anyone who dares ask for their vote. Even Nicola Sturgeon says she likes him, external.

While he generally trails Ms Sturgeon, Mr Sarwar's ratings are significantly in advance of those of Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Scottish Tory leader Douglas Ross or indeed Mr Starmer.

This may be one reason why Labour ended up running many of its social media ads during May's Holyrood campaign through his personal profiles, rather than those of the party. His face was plastered on the side of a campaign bus for "Anas Sarwar's Labour".

The elephant in the room is that this personal popularity did not translate into electoral success. Mr Sarwar seems to have been handed a pass for this, given he was dropped into the role literally a matter of weeks before polling day, but any political honeymoon is unlikely to last long.

The next Holyrood election may be years away, but the new leader needs to act swiftly if he is to re-establish Labour as a relevant player in Scottish politics.

Labour put Anas Sarwar front and centre in its Holyrood election campaign

A lack of safe seats - and targets

A major question facing a Labour fightback is where it starts. Where are the party's heartlands, in 2021? Where are its target seats?

The SNP has solidly colonised its old core territories, and Labour now has just two constituency seats at Holyrood - one of which, Edinburgh Southern, roughly lines up with the party's sole Westminster seat.

In May's Holyrood election, Labour was only in second place in a single constituency which could be considered a marginal seat, with a majority of under 10%. That was East Lothian, which was an SNP gain.

The electoral map for Westminster elections is similar. Labour was in second place in four marginal seats in 2019 - all seats it had previously held, and lost to the SNP on the night.

So on the face of it, the party might struggle to decide where to target its resources in a future contest.

But helpfully, in Scotland an election is never far away. Council polls are due in 2022, and will provide a key test of where the party's local support lies in various parts of the country.

Local authority ballots may not be big-budget affairs like referendums and national elections, but they are an important barometer of how parties are faring at the grassroots level.

Mr Sarwar will be under pressure to reverse the losses of 2017 if he is to build a platform for future Holyrood and Westminster contests.

May's election results suggest Labour has few obvious target constituencies left in Scotland

What is Labour for?

Labour's challenge isn't just about where in the country the fightback begins. It's also about where the party sits on the political spectrum.

The 2021 election underlined that politics in Scotland is an increasingly binary affair. Tactical voting is common, with many seats a race between the SNP and the party deemed most likely to challenge them.

The question for Labour is how to be that second party, when it has ended up a third wheel in many of the big debates of the day.

Whichever way you slice Scotland's many political rows it seems like the SNP and Tories have the key positions locked up, as the parties of Yes and No, Remain and Leave and indeed Left and Right. This suits both of those parties fine, and they are delighted to shut Labour out in the cold.

Labour has bled votes to both ends of the spectrum as these debates have dragged on - and tacking hard to one side or the other has not helped, as Kezia Dugdale found with her cast-iron opposition to independence.

Fundamentally what Labour needs is a compelling narrative. Proof of purpose. A unique story it can tell to the electorate and say "this is what we are for".

Mr Sarwar's pitch in May was to point to the pandemic and the recovery to follow as a compelling new topic of debate, in an attempt to break new ground which could prove more fertile for his party.

He would be helped enormously if Mr Starmer's project bears fruit at Westminster, because it would help break up the "SNP versus Tory" duopoly which holds sway in Scottish political debate.

And for his part, Mr Starmer will take extra seats anywhere he can get them in his mission to end his party's long run on the wrong side of the House of Commons.

These two leaders may need to succeed in tandem if they are to have any chance of leading Labour out of the political wilderness.