How are the Scottish Greens settling in to government?

- Published

The Scottish Green Party has held its first conference as a party of government, with leaders promising that they are "only just getting started" with tackling climate change.

The party has a less prominent position in parliament now, having forfeited speaking slots at Holyrood's primetime events like first minister's questions in its deal with the SNP. But with Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater in ministerial offices, will they be able to deliver on big policies and make the pact worthwhile?

Rocky start

The partnership had a difficult first few weeks, with events conspiring to throw up a series of wedge issues which threatened to drive the two parties apart.

There was the Cambo oil field, and Nicola Sturgeon's attempt to sit on the fence about it even as the co-operation agreement was being finalised.

Then there was vaccine passports, which the Greens had been quite critical of but were bound into backing amid constant opposition pressure.

This rocky start was in many ways an object lesson for the Greens in the trade-offs involved in government, where pragmatism is often as important as principle.

James Shaw - a co-leader of the New Zealand Greens who are part of a similar partnership arrangement - told the Scottish party that they would have to "swallow a few dead rats" in order to occupy a position of influence.

They might have hoped to wait a little longer before tucking in, but the good news for the Greens is that the partnership stood the test. Perhaps it will be all the stronger for having been tempered in the heat of a political rammy, rather than having a stress-free honeymoon period.

And they can now look ahead to opportunities as well as challenges, with the COP26 summit in Glasgow looming.

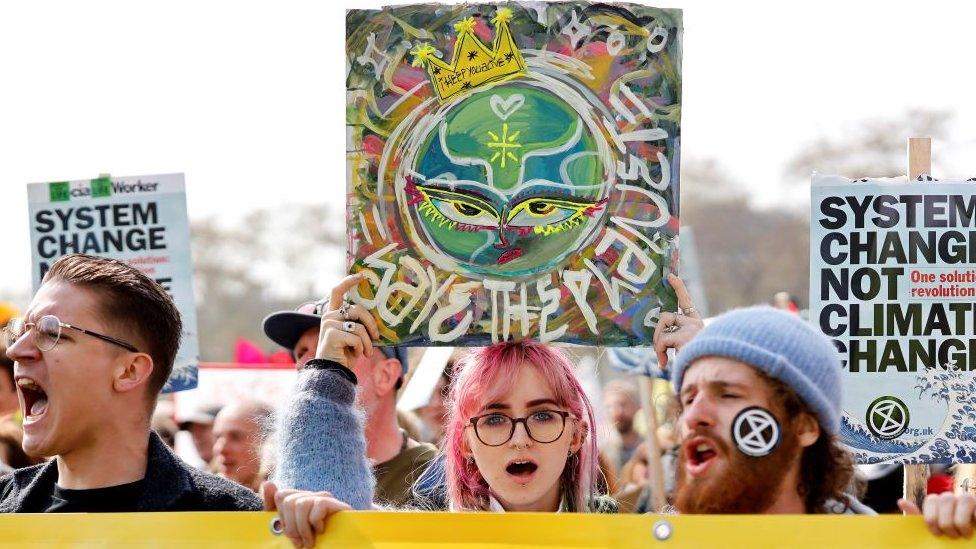

In government the Greens will have to lead action against climate change, rather than protesting and lobbying decision-makers

Taking office

On the eve of the conference, Patrick Harvie made his first ministerial statement to the Holyrood chamber - a landmark moment for Green politics in the UK.

It was also another crash-course in the challenges of government, as the minister faced tough questions about how to pay for a decarbonisation project which could cost £33bn.

It will be interesting to see if these parliamentary set-pieces become a more regular feature as Mr Harvie and his co-leader Lorna Slater settle into their roles. As it stands, other than popping up to answer the occasional portfolio question they seem to have disappeared into the depths of St Andrew's House.

Perhaps this is understandable, as they adapt to new circumstances and get their feet under the table. But as part of a large team of junior ministers, Mr Harvie and Ms Slater may ultimately have a similar profile to that of, say, Ben Macpherson or Ash Denham - regardless of how ably they lead their portfolios, they do not enjoy hours of airtime.

There is a ministerial pecking order, which starts (and often ends) with Nicola Sturgeon and John Swinney, before moving to cabinet-level ministers and only then to more junior figures.

This taps into an age-old dilemma for politicians, and a familiar one from the Labour Party's latest bout of introspection. Would you rather be seen and heard and "win the argument", or actually get stuff done with less in the way of bombast?

Governing is not a straightforward business, particularly when you want to make radical changes. Guiding a single piece of legislation through parliament requires countless hours of consultation, wrangling with lawyers over redrafts, seemingly endless committee appearances, and horse-trading over tinkering amendments.

Most of that graft does not take place in the Holyrood chamber or in front of a camera. Mr Harvie and Ms Slater may become more anonymous figures than they were during the election campaign, or even at any point when the Greens were in opposition - but they could have the reward of seeing some of their policies become laws, a legacy which will last far longer than a good clip from FMQs.

Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater now part of the ministerial pecking order, some way behind Nicola Sturgeon

Parliamentary arithmetic

It isn't just the Green leaders who have experienced a trade-off of airtime for influence.

The party has had to give up many of its prime speaking slots at Holyrood; at first minister's questions, responding to statements and motions, and in leading their own chamber debates.

And with the co-leaders closeted in ministerial offices and Alison Johnstone off to become presiding officer, it has been left to less experienced voices to take centre stage at Holyrood.

Ross Greer, recently the parliament's youngest-ever MSP, is now an elder statesman of the Green MSP group, while newly-elected Gillian Mackay has been catapulted into a lead role.

This might chiefly be of interest to dedicated viewers of Parliament TV - a small but proud slice of the voting population, for all that it has a knock-on effect in how much coverage the Greens get in broadcast reports and print media.

The thing is, the very fact of the deal, giving the government an automatic majority and neutering the opposition, has taken some of the intrigue out of proceedings at Holyrood. There is little jeopardy or risk of an upset.

This security is essentially what the SNP were looking for in the pact, and as such it may be in the party's interest to give their junior partner the odd headline-grabbing platform in parliament.

But with the government more comfortable than at any point since the SNP took power, it could well be preferable to have a small voice inside the administration than a big one in opposition.

The co-leaders heading for St Andrews House has thrust some new Green MSPs like Gillian Mackay into the spotlight

Longer term

Green issues will be to the fore in the immediate future, thanks to the COP26 summit in Glasgow.

It is not yet entirely clear what Nicola Sturgeon's role is to be in the conference itself, so it is equally mysterious what part her junior ministers might play.

But the hope is that the event will set the table for a longer political conversation about climate change and what can and must be done about it.

The plan for the Greens is that from within government, their part in that conversation can be a prominent one - perhaps even beyond the domestic stage.

In any case, it is far too early to evaluate whether the SNP-Green deal is working out. The pact is only six weeks old, and is due to run for a five-year parliamentary term.

Change does not happen quickly, and nor does legislation. It may be years before we can properly determine what the Greens have got out of it, and what they have had to give up in return.

And obviously, the ultimate jury will be the electorate. Five years is a long time in politics, and if things go to plan for the SNP and Greens, Scotland could be a very different country by the time voters next go to the polls to elect MSPs.

You might also like these analysis pieces

Does Johnson's vision work for Scotland's Tories? - The Conservatives in Scotland have cemented second place at Holyrood - but what is the party's long-term goal?

Can Labour find a way back in Scotland? - Party leaders Anas Sarwar and Keir Starmer both need to succeed if either is to have a future.

- Published10 October 2021

- Published9 October 2021