UK government argues MSPs do not have power to set up indyref2

- Published

The Scottish Parliament "plainly" does not have the power to set up an independence referendum, UK government law officers have argued.

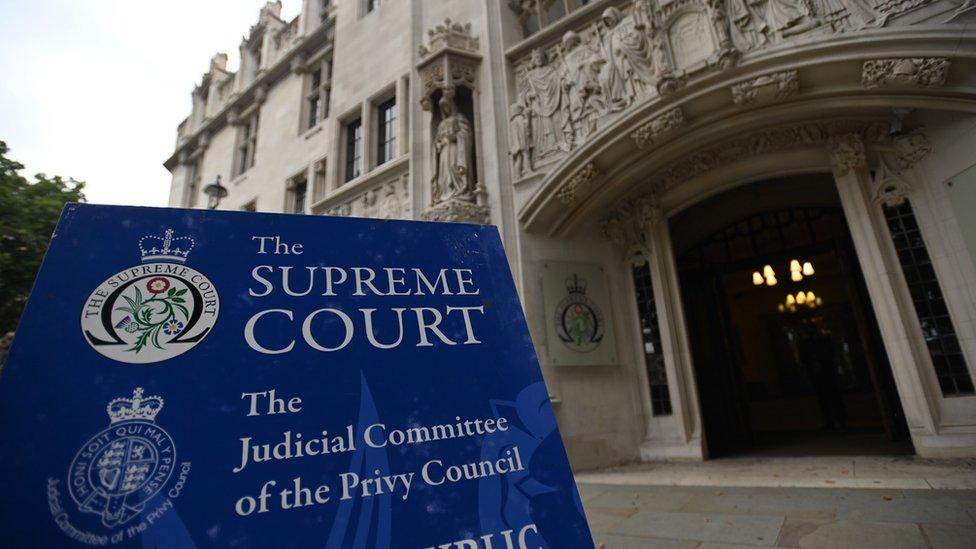

The Supreme Court is to look at whether MSPs can legislate for a vote without Westminster's backing in October.

The Scottish government has argued that any vote would be "advisory" and would not directly break up the union.

But UK law officers said there was "no secret" that Scottish ministers would want the vote to lead to independence.

Papers published on Wednesday, external said a referendum was "not designed to be an exercise in mere abstract opinion polling at considerable public expense", and it would clearly be used to push for "the secession of Scotland" from the UK.

Judges will hear arguments at the court in London on 11 and 12 October.

The SNP has also applied to intervene in the case to make additional arguments in favour of a referendum.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon wants to hold a vote on independence in October 2023, and has been pushing the UK government to agree to this.

However in the absence of a deal she also wants judges to rule on whether Holyrood has the power to set up a vote without Westminster support.

The case has been referred to the Supreme Court by Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain, the Scottish government's top law officer, in a bid to clarify whether MSPs can pass legislation paving the way for a poll.

Constitutional matters including the union are reserved to Westminster, but Ms Bain has argued that an "advisory" referendum would not necessarily cut across this.

The QC said that the vote would have "no prescribed legal consequences arising from its result", and that it would be for politicians to decide what to do afterwards.

Ms Sturgeon has argued this was also the case with the 2014 independence referendum and the 2016 vote on EU membership, which led to years of negotiations and bills being passed before Brexit actually happened.

The UK government meanwhile does not want judges to rule on the case at all, arguing that it would be premature to decide anything before a bill has been passed by MSPs.

Papers lodged on behalf of the Advocate General for Scotland - Lord Stewart of Dirleton, the UK government's top Scots law officer - argue that the court would not normally give "advisory opinions on abstract legal questions".

Legislative disputes between the Scottish and UK governments are heard in the Supreme Court in London

The submission also states that "the Scottish Parliament plainly does not have the competence to legislate for an advisory referendum on the independence of Scotland from the United Kingdom".

On the idea of a vote being "advisory", the submission said there was "no secret" about the Scottish government's intentions.

It added: "It cannot be credibly suggested that the outcome of the referendum will be 'advisory' in the sense of being treated as an academic interest only.

"A referendum is not, and is not designed to be, an exercise in mere abstract opinion polling at considerable public expense.

"Were the outcome to favour independence, it would be used - and no doubt used by the SNP as the central plank - to seek to build momentum towards achieving that end: the termination of the union and the secession of Scotland."

There are few surprises in the UK government submission - it is fairly straightforward, that Holyrood doesn't have the authority to set up a referendum.

It is however slightly awkward for this to be stated so baldly.

UK ministers have previously preferred to stress the breadth of devolved responsibilities, painting Holyrood as one of the world's most powerful devolved parliaments.

That allows them to put pressure back on the SNP over the running of services in Scotland, and avoids the impression of telling MSPs to get "back in your box".

It's also why they tend to say "not now" to a referendum, rather than a flat "no". But putting it into bare legal terms removes the softer edges of political messaging.

It all underlines that the outcome of this case will cause a political storm no matter the result.

Should the UK government's legal arguments win out in the Supreme Court, they will immediately become political arguments for Ms Sturgeon to use in the court of public opinion.

A very public demonstration of the limits of Holyrood's powers could be a cornerstone of her case for why it should have more.