Scottish independence: a choice of uncertainties

- Published

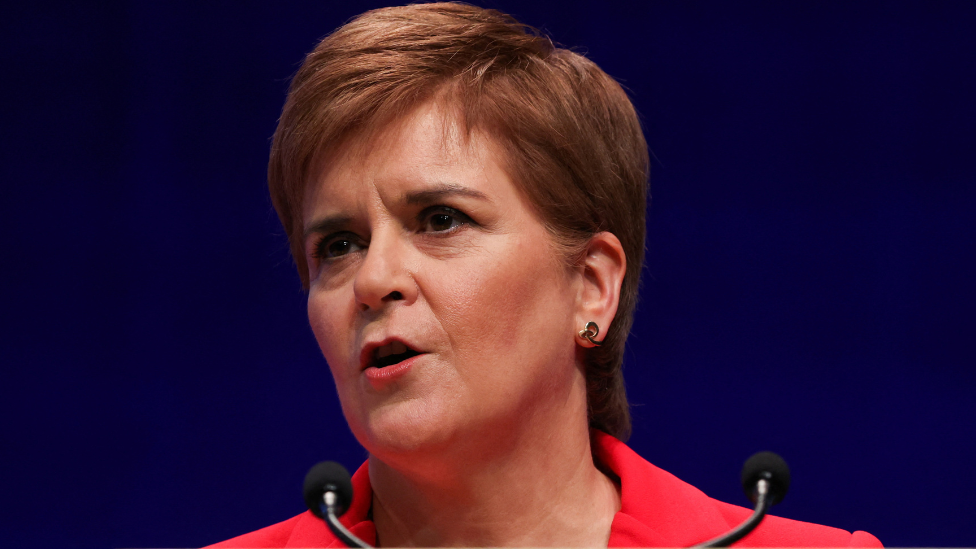

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon launched the latest in a series of papers on independence on Monday

The astonishing reversal of the Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng budget threatened to eclipse an important day for the cause of Scottish independence.

Jeremy Hunt was sidelining a prime minister who is little more than a month in the job, while sucking much of the air out of news media space.

But with eclipse came opportunity. The new Chancellor of the Exchequer was also providing the latest episode in a series of events that could hardly have done more to weaken the case for Scotland remaining in the UK because of its long-standing stability, a reputation for good governance or its international standing.

Speaking from her Bute House official residence, Nicola Sturgeon slotted home that shot at an open goal, before embarking on an economic case which sought to balance attack with defence.

On the front foot, the document, external offers a vision of a fairer, green Scottish economy. Lots of Scots can sign up for the list of improvements. They reflect on what is perceived to be a different consensus or middle ground in Scottish politics.

But the vision is little more than a wish list. We can attach our own preferences, and project them on to this blank screen of possibilities. To make them into a reality requires the choosing of priorities, building of alliances, in many cases finding the funds, and addressing the areas where there are potential trade-offs.

For instance, you can raise minimum wages for young people, but in a less tight labour market than we currently have, what if that prices them out of the market for jobs which can be done by someone with more experience?

More obviously, while there are positives about membership of the European Union - freedom to live and work in the EU among them, and to recruit from the EU - there are negatives about the potential trade friction with the rest of the UK.

'Easier said than done'

Nicola Sturgeon's defences are taking more time and effort.

The transition to a new currency remains a hard one to sell to the public, when so much of the plan is uncertain, and it depends on moving parts over which even an independent country has little or no control.

The gap between spending levels and estimated tax take from Scots starts off at an unsustainable level. And if those aspirations for a different type of economy are to be met, the gap can be expected to grow.

The plan promises the kind of fiscal discipline rules and institutional safeguards that are intended to avoid the debacle that befell the Truss/Kwarteng budget. But by pointing to the volatility of figures throughout Covid and now the surge in inflation, they decline to say how tight the squeeze might be on spending.

Ms Sturgeon said an independent Scotland would keep the pound and move to its own currency when the "time is right"

Until the Scottish Fiscal Commission gets to look at the actual numbers facing an independent Scottish government, we won't have an independent assessment of whether the hoped-for growth is likely to materialise.

Both of these issues are highlighted by the Institute for Fiscal Studies. The economic blueprint "makes all the right noises on how the public finances would be managed, emphasising achieving fiscal sustainability," says the IFS's David Phillips.

"But it skirts around what achieving sustainability would likely require in the first decade of an independent Scotland: bigger tax rises or spending cuts than the UK government will have to pursue."

He goes on to say that Scotland could grow its way out of Britain's low productivity, "but boosting productivity and growth is far from certain and would be easier said than done.

"Experience from recent weeks [in Downing Street] suggests the markets may not look favourably on fiscal plans built on the uncertain hope of a substantial future boost to growth."

'Injection of candour'

These are not new challenges, and nor are the policies newly minted. They are close to the position adopted by the SNP when its policy absorbed the whole of the Sustainable Growth Commission, external in 2018.

That set out the route from sterling to a Scottish currency, and illustrated it with at least nine years of spending being squeezed.

Other significant changes since the 2014 referendum include Europe, with Brexit forcing a different approach. It is the main justification for pushing the case to another vote. Becoming a member offers a trading advantage over the rest of the UK. But it presents the problem of the England-Scotland frontier becoming a hard border.

Oil and gas is no longer to be the fountain of cash with which to balance the books. But old habits die hard. While Ms Sturgeon is against further oil and gas developments and would not use oil revenues for day-to-day spending, she is looking to its tax revenues to fill up a big trust fund, while she's already allocating the earnings from that investment fund many years in advance.

There was another change in the economic case being made. It was an injection of candour about the difficulties and uncertainties.

Eight years ago, questions and doubts were brushed aside as "Project Fear". Nicola Sturgeon now acknowledges the right that people have to question and to doubt, and the responsibility she has to provide persuasive answers.

Back in 2014, Alex Salmond said he knew the minds of Whitehall ministers, and would bend their opposition to his will through the force of his negotiating skills. After the experience of Brexit, it's harder to argue that such negotiations would be easy.

Ms Sturgeon knows there are uncertainties. What has significantly shifted in her favour is that the UK also brings an unprecedented period of uncertainty. Brexit is a journey to an unknown destination. The governing party at Westminster is severely weakened and divided by events of recent weeks.

A referendum this time next year would not be a choice between radical change and the status quo, but between two routes - both quite radical and both quite risky.

This would not be a choice between certainty and uncertainty, says Nicola Sturgeon, but between different uncertainties. The question, she adds, is how best to navigate them.

On an issue of profound division in Scotland, the first minister might even get agreement on that much.

- Published16 October 2022

- Published10 October 2022

- Published14 June 2022