Where do Tories stand in post-Sturgeon Scotland?

- Published

The Tories appear to be having a great time amid SNP struggles - but are their own prospects on shaky ground?

The Scottish Conservatives are holding their conference in Glasgow at a moment of flux and uncertainty in the nation's politics.

What does Nicola Sturgeon's departure mean for the balance of Scottish politics, which the Tories have been happy to keep on a constitutional theme? And how is Rishi Sunak's UK government shaping up to deal with Humza Yosuaf as first minister?

On the surface, the Scottish Tories appear to be having a marvellous time with the SNP's ongoing woes.

Leader Douglas Ross opened his conference speech with a lengthy string of gags at the expense of his rivals, as part of his one-man mission to exhaust every possible pun on the subject of motorhomes.

But for all this glee, there is a question over how ready his party is for the sands of Scottish politics to shift.

The Conservatives were quite comfortable with the post-indyref setup, contesting a never-ending constitutional squabble with the SNP - the parties of Yes and No, yin and yang - which left little room for Labour.

Ms Sturgeon was a useful bogeyman both for the Scottish party to scare up unionist voters, but also for the UK-wide operation to portray as a potential puppet master pulling the strings of a Sir Keir Starmer government.

Now she is gone, and uncertainty abounds.

They may talk a cheerful game, but the Tories' own fortunes are not exactly looking rosy, with polls suggesting they are well adrift of Labour in Westminster voting intention.

That, in part, explains why Mr Ross waded into a row over tactical voting.

It started with a newspaper column, external suggesting that Scottish voters would know which party was best placed to take on the SNP in their local area. He didn't actually say "vote Labour", but the inference was clear.

Mr Ross knew the SNP would pounce on any suggestion that the "Better Together" alliance of the 2014 independence referendum could be resurrected.

He also knows that Labour are desperate for the next election to hinge on anything other than the constitution - the topic which has seen them squeezed out into third place.

So anything that turns Scottish politics back into a binary bunfight over borders will implicitly damage Labour and benefit the Tories.

Hence why Mr Ross spent a good chunk of his speech wiring in about the SNP, and only a few lines writing off Labour as an insufficient challenge to them.

The attempt at 3D chess strategy was not publicly embraced by the prime minister, though.

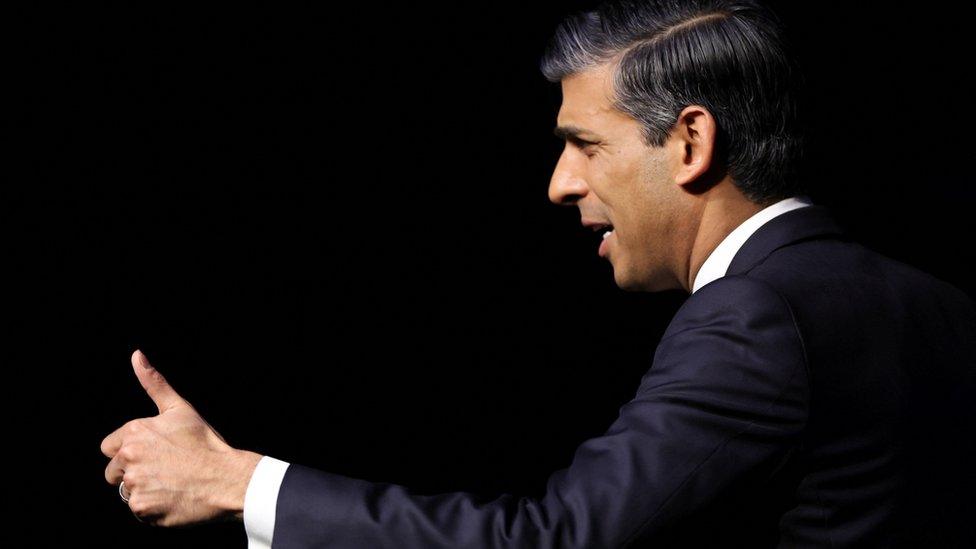

Rishi Sunak has a very different struggle with Labour on his hands, and is very clear that Conservatives should vote Conservative.

The UK government perspective may not be hugely different to the Scottish Tory one overall though.

They too are pretty comfortable with how things stand between themselves and the Scottish government, particularly when it comes to the constitution.

In his rather brief speech to conference - it lasted just over seven minutes, before he took part in a Q&A session with the less than fearsome inquisitor, Douglas Ross - Mr Sunak stuck with the tried-and-tested approach of insisting he would say no to any request for an independence referendum.

Rishi Sunak was the fourth successive PM to reject Nicola Sturgeon's calls for a referendum

"Now is not the time" was first dreamed up by Theresa May six years ago, and is perhaps her most lasting contribution as prime minister.

Nicola Sturgeon used to insist that position would crumble; instead it endured through the reigns of Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, and indeed has outlasted her own time in office.

The latest variation on the theme was beamed across the back of the stage during Mr Sunak's speech: that he is "focused on Scotland's real priorities", not independence.

Humza Yousaf formally asked for a referendum on his first day as first minister, and nobody was surprised when Mr Sunak shot the idea down immediately.

Somehow, over the years of polarisation and court cases and start-stop demands for a constitutional showdown, the idea that the UK government can simply ignore the demands of the majority of MSPs - at least when it comes to independence - has become an everyday feature of political life.

Perhaps that is why Mr Yousaf is now looking at playing a longer game, focusing on grassroots support rather than forcing the issue with Downing Street.

Alister Jack has served three Tory prime ministers as Scottish Secretary

Another constant during the revolving-door era at Downing Street has been Alister Jack, the Scottish Secretary who has now served three prime ministers.

On his watch, UK government's approach to dealing with devolution has developed through something known as "muscular unionism" into Arnold Schwarzenegger level body-building.

That is partly about being seen to do things for people on the ground in Scotland - directly funding local projects and infrastructure. But it has also involved more than a few clashes.

The previously iron lines of the Sewel Convention - that the UK government would "not normally" legislate across devolved areas - were breached during rows over Brexit. It may not be entirely normal, but it is hardly rare nowadays.

Precedent was similarly busted when the UK government used a dusty section of the Scotland Act for the first time ever to block Holyrood's gender reform legislation.

And UK ministers had few qualms about holding up the Deposit Return Scheme via the Internal Market Act - another piece of post-Brexit legislation detested by Scottish ministers.

The government in Edinburgh has loudly decried each of these moves, and indeed is challenging the blocking of the gender reforms in the courts.

Mr Yousaf might hope to shift relations onto a different footing in time, but on his first visit to London earlier this week he was received in Mr Sunak's House of Commons office rather than being afforded the diplomatic pomp of Downing Street, and the pair didn't even pose for a picture together.

Lord Frost was the man behind Boris Johnson's Brexit negotiations - but Scottish Tories reject his influence now

Constitutional conflict between the two governments has become normalised, and it seems the UK government side are ever-less shy about throwing their weight around.

There are limits, though.

Scottish Tories are running a mile from the position of Lord David Frost - the former Brexit negotiator who penned a column suggesting that devolution could be rolled back.

That successfully baited more than a few clicks, but was roundly rejected by Conservative MSPs as the haverings of a man whose period of influence ended a couple of prime ministers ago.

They know that kind of talk can only be damaging to their prospects in Scotland, where devolution has become pretty well entrenched.

Lord Frost's intervention raises questions about whether that message resonates as strongly among Tory politicians south of the border.

Mr Sunak read the room at conference and lauded Holyrood's range of powers from the stage. His line is that the SNP isn't making great enough use of them, not that they should be stripped away.

But the prime minister did not display pitch-perfect understanding of Scottish politics during his trip to Glasgow - which it turns out was so brief because he was also addressing the Welsh Conservative conference later the same day.

Mr Sunak walked into a needless and self-inflicted row with the Holyrood press pack after his team attempted to restrict access to a post-speech media huddle.

One staffer - presumably jokingly - suggested to the hacks that they could delete their tweets about the bust-up after the attempted restrictions were roundly ignored.

Journalists famously take well to such suggestions from central government, so the predictable end result was even more tweets.

In the end the press were allowed access to a session which lasted about as long as Mr Sunak's mini-speech.

It all added up to a gathering which was set up to revel in the struggles of a rival party - but which underlined that political difficulties are by no means unique to the SNP.

- Published29 April 2023

- Published28 April 2023