Why does the Scottish government keep losing court cases?

- Published

The Scottish government's failed legal challenge against the blocking of Holyrood's gender reform bill is the latest in a series of judicial defeats.

One of the country's most senior judges, Lady Dorrian, told MSPs last week that 4,946 civil cases involving the government have come to court between April 2016 and November 2023.

Some of those have been high-level litigation, from challenges to domestic policy to constitutional clashes between governments. And in many, the government has come out on the wrong side.

Why has our politics ended up in the courts so frequently? And why does the Scottish government keep losing?

Constitutional clashes

Disagreements between the SNP-led administration in Edinburgh and the Conservative one in London are unsurprisingly frequent.

The schism between the governments has widened during the turbulent times of late, and tumbles into the courts on a regular basis.

The Supreme Court has been called in on multiple occasions to rule on the scope of Holyrood's powers.

Brexit lit the blue touchpaper when the UK government decided to plough ahead with its flagship Withdrawal Bill against the express wishes of MSPs - prompting them to pass their own legislation.

UK law officers then challenged the Holyrood "continuity bill" at the Supreme Court.

The bill fell down on one ground, but the judges said it could have stood up on most others - "as a whole" it was within devolved competence.

However it transpired that after the bill passed, UK ministers had added their own Withdrawal Act to a special list of bills which cannot be modified by the devolved administrations.

That meant great swathes of the continuity bill were rendered unlawful - and Scottish ministers were furious, saying the goalposts had been moved mid-match.

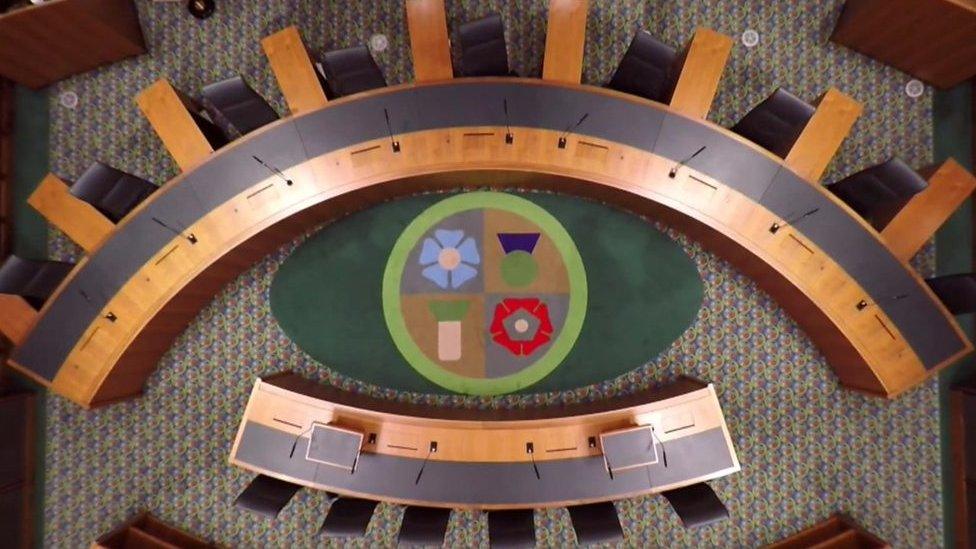

Legislative disputes between the Scottish and UK governments are heard in the Supreme Court in London

Since then, the two governments have rarely hesitated to take each other to court.

UK law officers have challenged several pieces of Holyrood legislation - one of which, on incorporating a UN charter on children's rights into Scottish law, has just undergone the parliament's first ever "reconsideration stage" to rectify issues flagged up by judges.

The Supreme Court actually said the bill had been "drafted in terms which deliberately exceed the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament", and it had to be stripped back.

The era of so-called "muscular unionism" continued with the UK government stepping in to block Holyrood's gender reform bill, with the first ever use of section 35 of the Scotland Act.

Scottish ministers then launched an equally unprecedented judicial review of that decision at the Court of Session, arguing that the Scottish Secretary Alister Jack had acted unlawfully.

That challenge was unsuccessful, with Lady Haldane ruling that Mr Jack had followed proper procedure - although the case may yet be subject to appeal.

Self-inflicted defeats

The Supreme Court rejected Holyrood's power to set up a referendum

The Scottish government has also resorted to the courts to pursue its own political goals.

In 2022, Nicola Sturgeon decided to ask the Supreme Court to rule on whether Holyrood had the power to legislate for an independence referendum.

Ministers accepted that the fate of the union was reserved to Westminster, but thought there might be a technical path to victory by claiming that referendum would only be advisory and not trigger independence on its own.

They were wrong, and the court unanimously ruled that MSPs could not set up a vote without Whitehall's approval.

The ruling has caused much head-scratching in the independence movement about the best way to proceed, with talk of using elections as de-facto referendums, or wildcat votes.

Alex Salmond first took the government he once led to court in 2018

There are more domestic cases too, like this week's spat with the Information Commissioner over whether details of the 2021 ministerial code investigation of Nicola Sturgeon should be subject to Freedom of Information (FoI) rules.

Some legal commentators have noted how swiftly the judges arrived at their decision, batting away the appeal without even leaving the courtroom to confer.

That case stemmed from an earlier judicial review, when Alex Salmond successfully challenged how the government investigated internal harassment claims against him.

Legal advice published during a Holyrood inquiry, external underlined the chaos in the government's efforts to defend against Mr Salmond's suit, with documents frequently unearthed late in the day and increasingly exasperated legal advisors threatening to quit.

He has now launched another court action, in a bid to win damages and force ministers to take accountability for the botched investigation.

Domestic policy rows

There has also been a steady stream of legal disputes over legislation passed and policies proposed at Holyrood over the years.

The record here is more mixed; the government did win a landmark case about minimum pricing for alcohol, which allowed a flagship policy to become law.

Ministers also successfully batted away a challenge to their policy of freezing rents and banning most evictions during the winter fuel crisis.

There was another victory in 2016 after Ineos sued over the government's "ban" on fracking - although ministers only won by arguing that they had not in fact banned fracking, and that SNP claims to that effect were a political "gloss".

Politics and the courts have collided more frequently in recent years

But there have been high-profile defeats too, which have derailed policies.

The Supreme Court shot downs plans for a "named person" scheme in 2016, and efforts to revive it fell apart at Holyrood over the following years until it was ultimately scrapped.

There was another defeat over the Deposit Return Scheme, although the policy had already been wrecked by a row with the UK government.

Frequently these reversals have come at the hands of campaign groups fronted by members of the public or businesspeople. They range across portfolios; there was one in the summer over scallop dredging.

Another, by the campaign group For Women Scotland, rendered part of a bill about gender balance on public boards unlawful - necessitating another piece of legislation at Holyrood make amends.

The cases can echo out to the frontlines of where policies are enacted too. City of Edinburgh Council has now suffered two defeats in the court about its short-term lets licensing regime - with the drafting of the original legislation at Holyrood at the heart of the cases.

A costly business

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC is the Scottish government's chief law officer, and occasionally represents ministers in major court cases

In one sense it doesn't matter whether the government has ended up in court due to a policy row, a constitutional showdown, disputes over drafting or a citizen challenge to a controversial new law.

The lawyers get paid either way.

In the really big cases the government is represented by its own law officers - like the Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC - who are at least on the payroll.

But they are generally supported by independent advocates, and take legal advice from external firms. None of that comes cheap.

The series of cases about gender balance on public boards have cost more than £200,000 to defend. The challenges to the named person scheme incurred costs of almost £480,000.

There has been a growing trend of campaign groups crowd-funding cases against policies they don't like. Legal academic Andrew Tickell has been tracking the topic and found millions of pounds has been pledged to litigation over recent years.

Alex Salmond solicited just over £100,000 of donations for his judicial review, and the government ultimately had to pay him £512,000 in costs when it admitted defeat.

The Information Commissioner has pointed to the fact that tens of thousands of pounds had been incurred in that case - and ultimately had been born by the public purse on both sides, during a much-publicised budget squeeze.

None of this is unique to Scotland - think of the big legal defeats the UK government has suffered over Brexit and its Rwanda policy.

And for all that ministers are always clear that they respect the role of the judiciary in the law-making process, they would surely rather not spend quite so much time in front of the courts in future.

Related topics

- Published8 December 2023

- Published6 December 2023

- Published24 November 2023