Scots farmers look at European exit

- Published

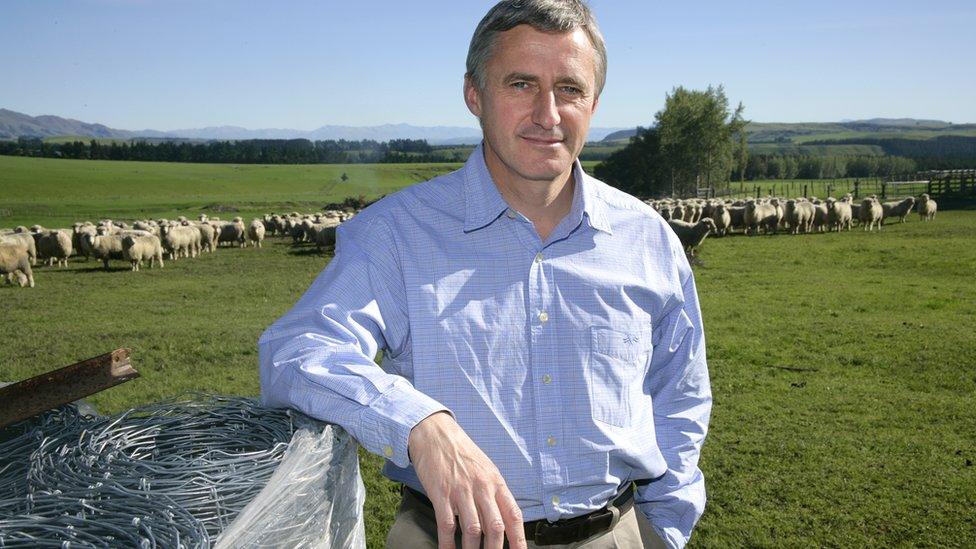

Andrew McCornick is typical of many Scottish family farmers.

He runs a beef and sheep business near Dumfries. He is also vice president of the Scottish NFU and understands more than most how much the industry is underpinned by European farm payments.

"I can't think there will be many farms that have a profit without the support from the EU," he admitted. "It is a big, big part of our income ... as the market isn't rewarding us for what we are doing."

In the last Common Agricultural Policy re-negotiation for the period 2014 to 2020 more than £4.5bn was earmarked for Scotland. With 500 million consumers, the European market accounts for 73% of the UK's agri-food exports, including 40% of Scottish lamb.

Andrew McCornick said the industry would have to make Brexit work

On the face of it, voting to leave that market would appear to be like turkeys voting for Christmas.

Stranraer dairy farmer Gary Mitchell, fed up of EU regulation and red tape, did exactly that.

"I grew up in a generation where we have been totally focussed on claiming subsidy on everything we do," he said. "We have to ask why are we doing it; running at a loss and hoping somebody's going to send a cheque from Europe to make up the deficit."

Mr Mitchell said it was time for change and Brexit was the opportunity.

"The whole European subsidy structure hasn't been working for the UK," he said.

"We are seeing incomes decline and production decline and we need to reverse that. That's what excites me about Brexit. We now have the power coming back into our own hands to make decisions that suit our rural economies."

Dr William Rolleston said nobody in New Zealand would want to go back to the days of subsidies

There is no clear vision as to what the future will look like or how we will get there, but might the UK look overseas to see how things might be done differently? New Zealand, for example.

Faced with a budget crisis in the 1980s, the Kiwi government scrapped farm subsidies altogether. The industry survived and, eventually, thrived although Dr William Rolleston, president of the Federated Farmers of New Zealand, conceded it wasn't easy.

"People had made a lot of investment decisions based on what they thought they were going to receive in income," he said.

"A number of farmers found it particularly hard and didn't survive the transition if they had maybe bought farms and borrowed heavily."

Dr Rolleson said farms, in general, got a bit bigger and farmers' outlook as well. The agricultural economy diversified and farmers were able to make decisions based on market realities and not what subsidies locked them into.

'Totally disadvantaged'

He said there was no prospect of turning back the clock.

"If you ask around the farming community in New Zealand, I don't think anyone would say we should go back to the days of the subsidies," he said.

"We see production subsidies a bit like social welfare; you get trapped into a particular system and it's just so hard to get out."

Getting out of the EU WILL be a catalyst for change in the UK, but is the New Zealand model the answer? Not according to Mr McCornick who pinpointed two reasons for the continuation of support payments in some form, particularly in Scotland.

"If we are trying to sell into a European market which is our nearest neighbour, farmers there will be still be receiving support," he said.

"We're going to be needing a similar kind of support or we're going to be so totally disadvantaged it will hardly be worth getting up in the morning."

Gary Mitchell said he was tired of the red tape coming from the European Union

"Also, the nature of the land in Scotland is challenging," he added. "Only 15% is prime arable land; 85% isn't. If you look across the border to England it's virtually the flip of that; 85% is better land.

"This (EU) support, it supports communities and it supports the food industry ... an important part of the Scottish rural economy and we have to have the basis to make that work."

The NFU are buying time to try to work out what does happen next. They've been told that most, if not all, of the funding that would have come from Europe from now until 2020 will be paid from UK or Scottish government coffers if Brexit is achieved before then.

Brexiteer farmer Mr Mitchell said that breathing space must be used well.

'Blank page'

He voiced optimism that a way could be found to reduce farming's reliance on subsidies. He wants the UK to be more self-sufficient in food and reduce its dependence on imports.

But he said farmers could still be competitive in a world export market eager to buy quality Scottish-label produce with the weaker pound already helping that.

Despite not wanting Brexit, Mr McCornick said it can, and must, be made to work.

"I wouldn't say it's a blank page, but we certainly do need to consider what market we are going to be supplying and how we get access to that market," he said.

"We've got to get all that pinned down and then we will see how things evolve and I think we can get something more bespoke to suit Scottish agriculture.

"We're outwith the EU and we have to deal with that."