How the Falkirk Wheel revived Scotland's canals

- Published

Eric Wightman campaigned for the maintenance of Scotland's lowland canals

Eric Wightman's life is intertwined with Scotland's canals.

Growing up in Polmont, near Falkirk, the banks of the Union Canal were his childhood playground. In adulthood he saw the Union and the Forth and Clyde Canals deteriorate.

Motorways and housing estates were built across them but mainly they were neglected and ignored - a dumping ground for shopping trolleys and other detritus.

Eric campaigned to save them but he hoped only to be able to maintain what was left, to stop them deteriorating further.

Twenty years ago the Falkirk Wheel changed all that.

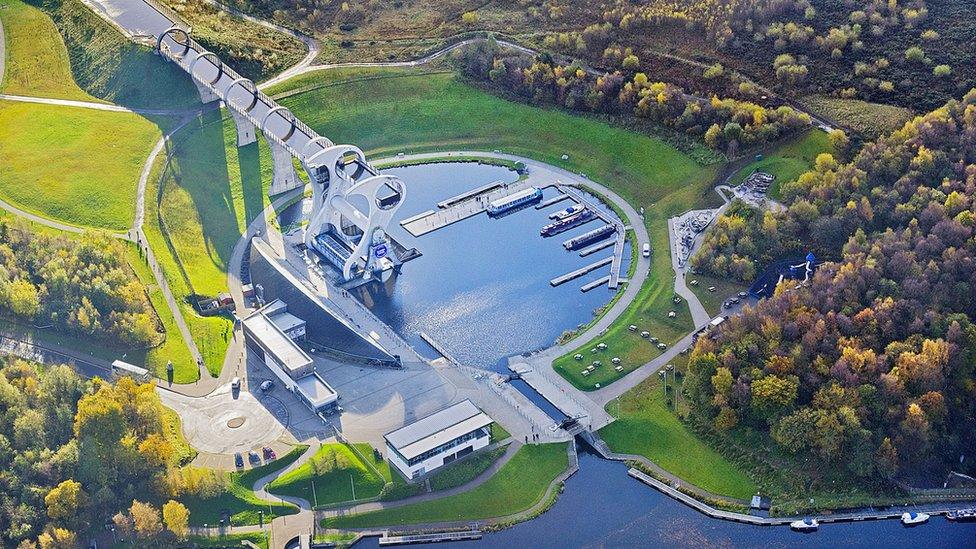

It was an ambitious project to link the Union and the Forth and Clyde canals, allowing boats to travel from coast to coast, right through Scotland's central belt.

But it did much more than that.

"I remember when they came up with [the design], I just couldn't understand it," Eric, 75, said. "When I saw it being built, I thought: 'This is something special'."

Boats are carried between the higher and lower canals on the Falkirk Wheel.

The 35m tall structure is the world's only rotating boat lift, bridging a gap once occupied by 11 locks which closed in 1933.

In a feat of engineering recognised with countless awards, it carries vessels between the canals in huge gondolas using the same amount of energy as it would take to boil eight kettles.

It is a structure which has attracted visitors from around the world, sparked a resurgence in the popularity of Scotland's canals and impressed a sense of pride in the people of Falkirk.

For Eric, the highlight came when he crewed a boat for the late Queen when she opened a new "missing link" canal in 2017.

It formed the eastern gateway to the Forth and Clyde canal and was built as part of the £43m Helix project, which includes the Kelpies sculptures.

The Queen officially opened Scotland's newest canal in 2017

She travelled in a boat called The Wooden Spoon, operated by the Seagull Trust which provides free barge trips for people with special needs.

"It was tremendous," said Eric, who volunteered with the trust. "We sailed up the canal, steam boats whistled, there were crowds, pipes and drums.

"And as she stepped ashore, there was a flypast with stunt planes. It was a super day."

It was a return to the area for the Queen, who had opened the Falkirk Wheel in 2002.

The new Queen Elizabeth II canal was the "final piece in the jigsaw", said Eric - but not something he ever imagined possible during his campaigning days in the 80s and 90s.

The Queen travelled on The Wooden Spoon when she opened the Queen Elizabeth II canal

The site chosen for the Falkirk Wheel in the 1990s was a tricky proposition for engineers working on the project.

To Eric and his peers, it was waste ground with a large puddle they knew as the "Irn Bru lake", a kilometre away from the locks which originally linked the canals.

It had been home to the Scottish Tar Works, where a fire in the 1970s burned for five days leaving a huge black cloud over Falkirk. Only the Forth and Clyde canal protected the community downhill from all the tar that escaped the site.

The presence of an opencast mine and the northern frontier of the Roman Empire - the Antonine Wall - also added to the engineers' collective headache.

Find more stories from Tayside and Central:

For Richard Millar, who joined British Waterways as a project manager in 1999, it was career-defining work.

"We had to design a canal that stretched the additional kilometre, we then had to find our way and create a new bridge under the Edinburgh-Glasgow railway line," he said. "We were only able to do that on Sundays because we were only able to get possession of the line on Sundays.

"Then we had to tunnel underneath the Antonine Wall, then build the aqueduct out, the Falkirk Wheel to drop us the 30m down to the basin, and then along and through the Jubilee loch and out to the Forth and Clyde canal.

"So, a massive engineering project in scale but delivered at pace."

It quickly became obvious to engineers working on the Falkirk Wheel that it would become a tourist attraction

At its peak, there were 1,000 people working on what was known as the Millennium Link project, which cost about £83.5m.

Their aim was to connect the canals with the Falkirk Wheel and to upgrade the waterways to enable boats to navigate successfully between Glasgow and Edinburgh.

But they did not anticipate the success of the towpaths which run alongside the canals.

"People have found their local towpaths, they're really busy, really vibrant," said Mr Millar, who is now chief operating officer with Scottish Canals.

And it was never more evident than during the darkest days of the pandemic, when almost everything else was closed.

A 500% increase in cycling and walking was seen on the towpaths.

The canals towpaths are popular with cyclists and walkers

"I remember that May just looking at the figures - we've got 55 pedestrian and cycle counters across the canal network - and we were able to see a massive increase in activity," Mr Millar said.

"What we also saw was people online buying paddleboards, kayaks and canoes. A lot of people found their local waterway whereas in the past they would have gone on holiday.

"And we're still seeing much more activity levels on the canal."

It has also led to increased investment and regeneration along the banks of the canal.

"We've seen almost 10,000 new houses, jobs created, new destinations, new cafes, pubs, restaurants and people actually living on the water," Mr Millar said.

"We now have - across Scotland's canals - 120 residential moorings where people live on a boat and have that joy of opening up the windows in the morning and seeing a swan just gliding by."

The Falkirk Wheel is the world's only rotating boat lift

Perhaps the biggest effect of the Falkirk Wheel and the renewed canals is less tangible however - it is the sense of pride among the people of Falkirk.

"As engineers we were building a boat lift to get a boat from the top of the hill to the bottom of a hill, but actually quite quickly it became obvious that it was going to be a tourist attraction," Mr Millar said.

"It was the start of a new change to Falkirk, it gave the people of Falkirk something to be proud of, it gave people a reason to visit.

"Suddenly in 2014, we saw an increase in tourism.

"There's no doubt the Falkirk Wheel and the Kelpies have earned themselves year in, year out, with both direct spend on the site with tourist perspective, and indirect spend with people coming to and spending time in Falkirk.

"But probably the biggest of all is the pride the people of Falkirk now have in their Kelpies and their Falkirk Wheel and that has been an incredible journey."

- Published21 April 2021