The students who stole the Stone of Destiny

- Published

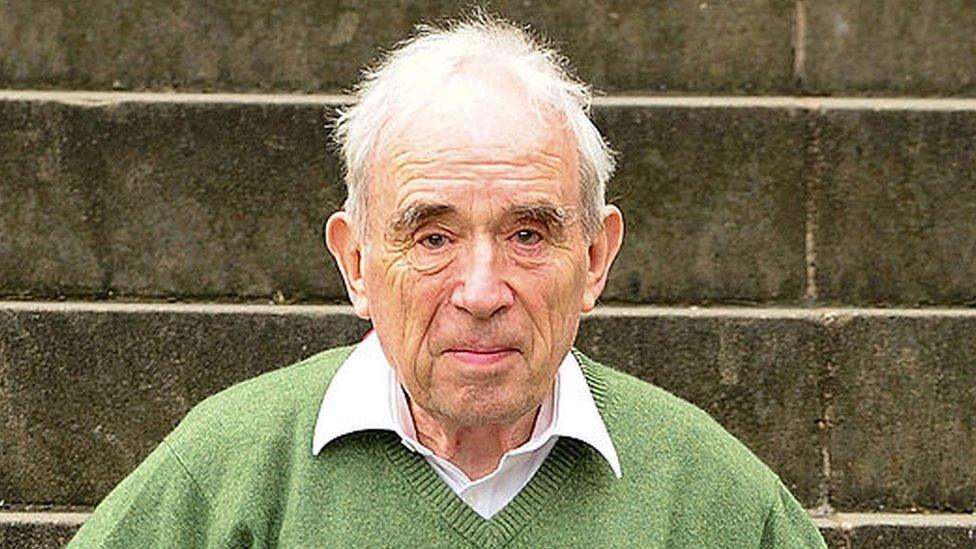

Ian Hamilton was a third-year law student at Glasgow University

Long shrouded in mystery and legend, the Stone of Destiny will be used in the Coronation of King Charles at Westminster Abbey in May. An ancient symbol of the Scottish kings, the stone was believed to roar with joy when it recognised the right monarch. In the 1950s, it was taken from London to Scotland in an audacious raid.

When a passing policeman saw a couple in a passionate embrace in a car outside Westminster Abbey in the early hours of Christmas Day, he did not for a moment consider they might be in the midst of one of the most audacious heists in British history.

It was 1950, and the man in the car was Ian Hamilton - a 25-year-old Glasgow University student who was intent on making a massive statement about Scottish nationalism.

The policeman had seen him jump into the Ford Anglia beside fellow student Kay Matheson, and had gone to investigate why they were parked in front of the Abbey.

The cuddling couple explained that they had just arrived from Scotland and could not find a hotel. The sympathetic policeman chatted to them before saying they would need to move on.

As he watched them drive away, he was unaware that concealed in the car was a broken chunk of the Stone of Destiny, the ancient symbol of Scotland, which had been seized six centuries earlier by English King Edward I.

Before the night was over, Ian Hamilton had snatched the other part of the 150kg (336lb) red sandstone block and spirited it away from the Abbey.

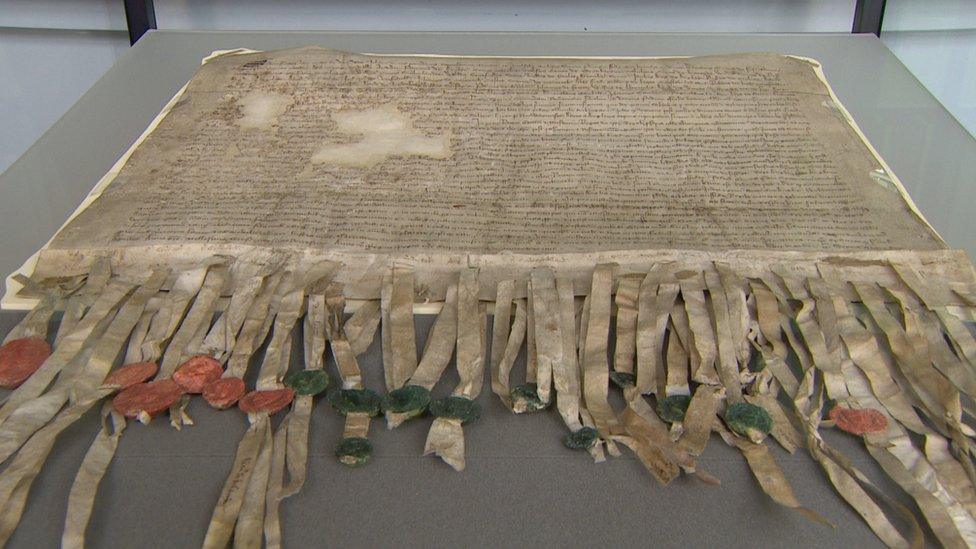

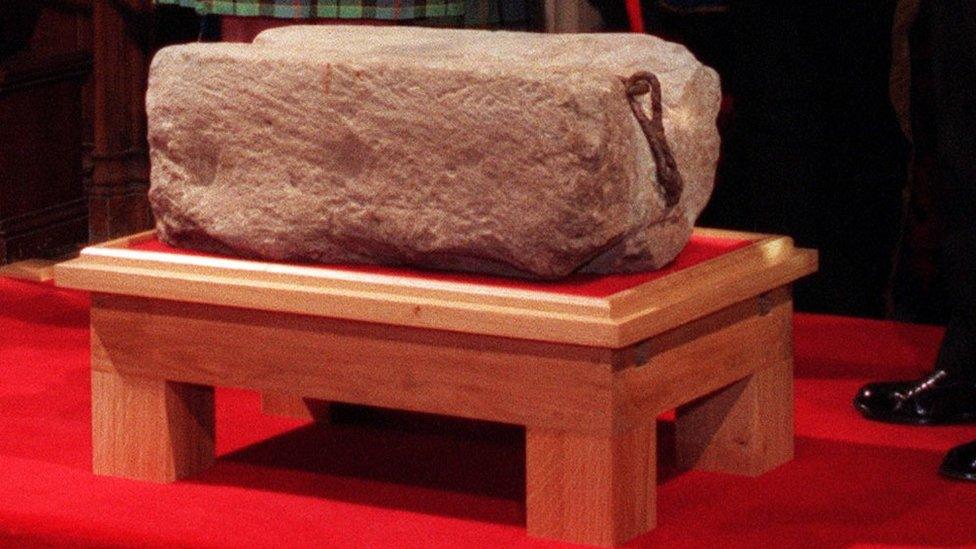

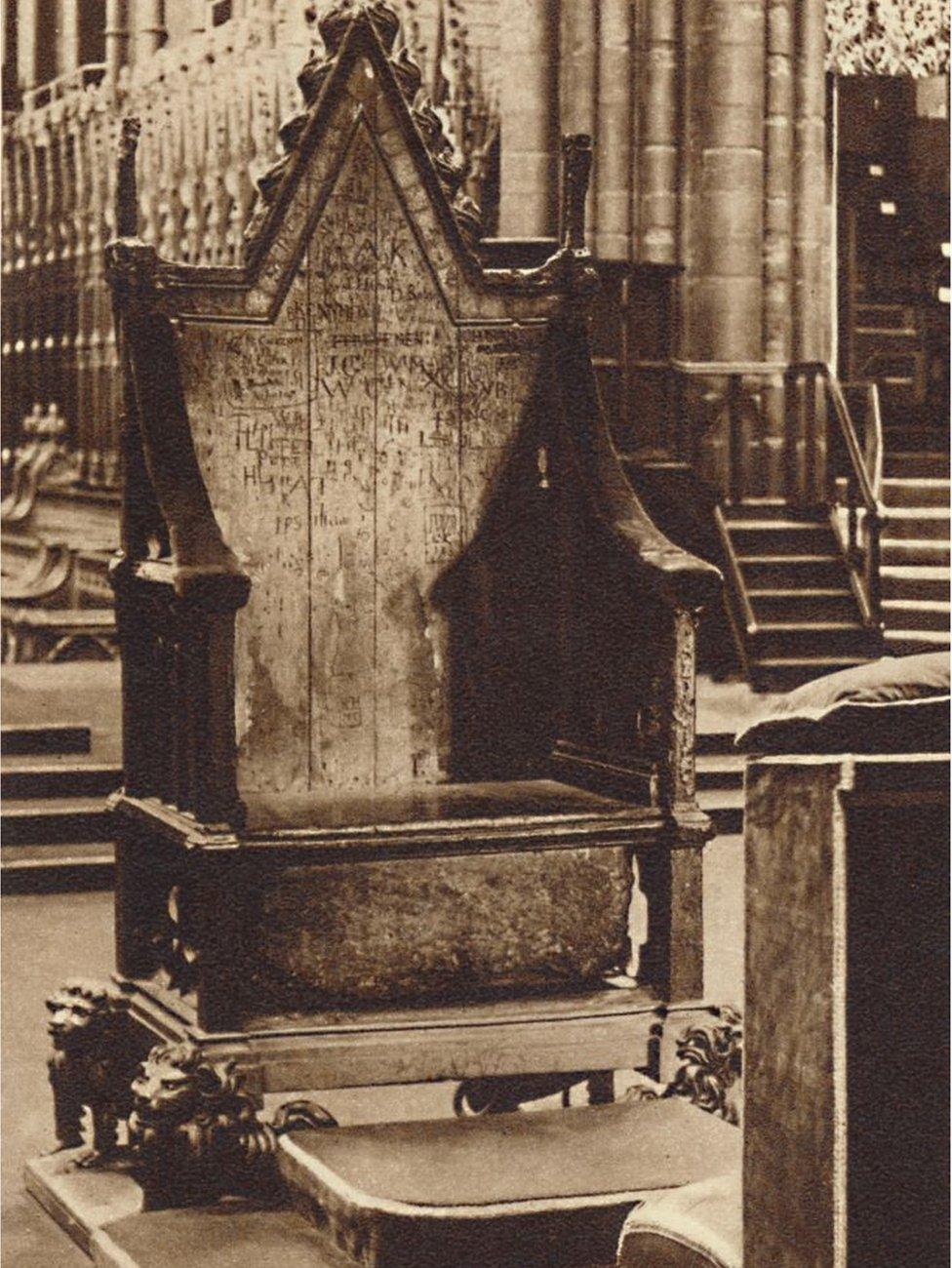

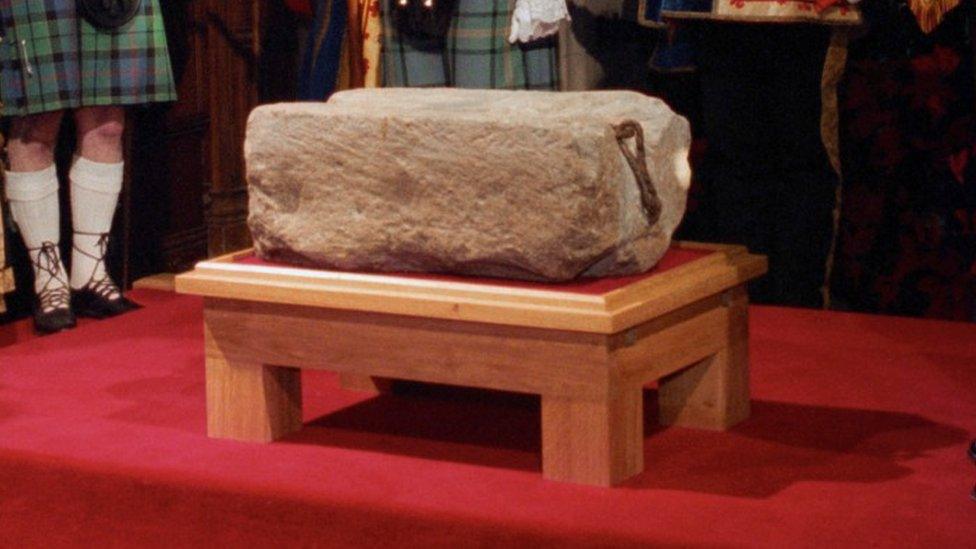

The Stone of Destiny, also known as the Stone of Scone, was used in the coronation of Scottish kings for hundreds of years before it was looted during the Wars of Independence and taken to Westminster Abbey where it was lodged in King Edward's carved-oak coronation throne

The Stone of Destiny was originally used during the coronation of Scottish kings

"The Stone of Destiny is Scotland's icon," Ian Hamilton, who died last year, told the BBC in a rare interview.

"In one of the many invasions by the English into Scotland, they took away the symbol of our nation.

"To bring it back was a very symbolic gesture."

So during the Christmas holidays from university the four students set off for London in two elderly Ford cars. The other members of the gang were Gavin Vernon and Alan Stuart.

Their first plan was for Ian to slip into a dark corner of the Abbey just before it closed for the night and later open the door from the inside. But the night watchman caught sight of him and threw him out, accepting the excuse that he had been locked in by accident.

This picture shows the Coronation Chair and the Stone of Destiny in 1937

The next night they tried again. By 4am, they had parked one of the cars nearby and driven the other right up the lane behind Westminster Abbey.

While Kay waited in the car, the men went up to the Poet's Corner door to try to jemmy it open.

Kay later said she was sure the noise could be heard on the other side of London.

Having managed to break open the door, the group were now feverish with excitement and set about removing the stone from its cavity beneath the throne.

They placed the stone on the floor and Ian took his coat off so they could use it to drag the block along.

They each took an arm of the coat and Ian took hold of one of the chains attached to the stone - but as soon as he pulled, the stone gave way and broke in two.

In shock, Ian said he picked up the smaller bit of stone, weighing about 90lbs (40kg), and ran with it as if it was a rugby ball.

The Coronation Throne in Westminster Abbey after the theft of the Stone of Destiny

Kay said she saw him coming out the side door of the Abbey.

"Then to my horror I saw this policeman looking down the lane," she said. "I realised if Ian crossed over to the car with the stone the policeman was bound to see him.

"So I drew the car in as closely as I could and Ian quickly pushed the stone into the back seat of the car and threw a coat over it."

After the encounter with the policeman, Kay and Ian set off with the smaller of the two pieces in the back of their Ford Anglia.

Gavin and Alan fled without the larger section, thinking they had been abandoned.

They did not know that Ian had got out of the car and was now making his way back to the Abbey.

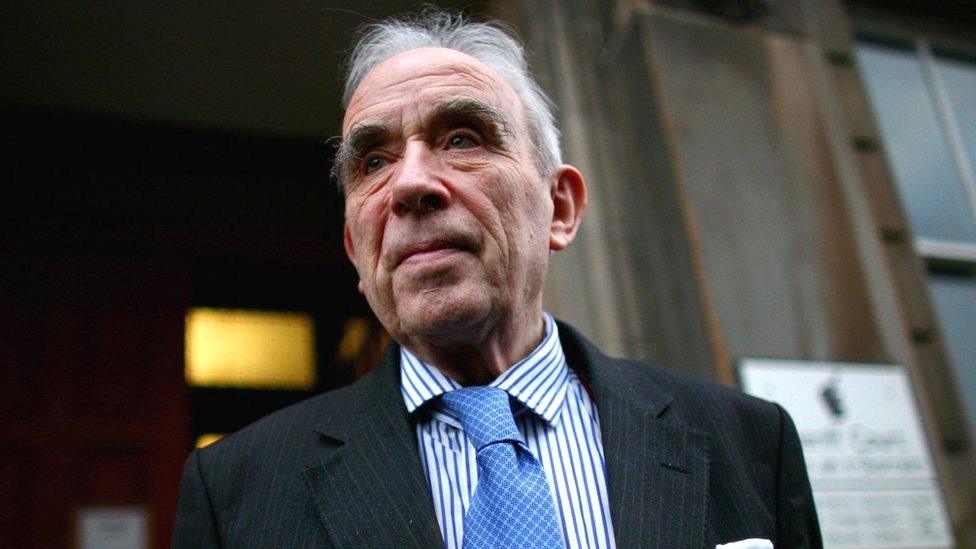

Ian Hamilton died in 2022 at the age of 97

The keys to the second car had fallen out of his coat pocket so Ian had to go back inside the pitch black church to find them.

In another stroke of luck, he found the keys when he stepped on them by accident near the door of the Abbey.

It was now left to Ian to manhandle the larger section of the stone into the boot of the car.

He drove away from the Abbey just as dawn was breaking - and by chance discovered Gavin and Alan plodding along, looking lost near the Old Kent Road.

The gang buried the large section of the stone in open country near Rochester in Kent.

Kay had left the smaller piece at a friend's house, and it lay in a garage in Birmingham.

The Stone of Destiny was left in Arbroath Abbey months later and returned to Westminster

When the theft was discovered it caused an international sensation and the border between Scotland and England was closed off for the first time in 400 years.

The Metropolitan Police had correctly assumed the stolen stone was heading north of the border, so a team of Scotland Yard detectives were sent to work with Scottish police.

Ian Hamilton said he had intended to leave the stone buried until the "hue and cry" had died down, but became worried about the effect of the freezing conditions on the stone that had not been exposed to elements for 600 years.

On Hogmanay - New Year's Eve - he set off with Alan Stuart and two others to retrieve the larger section from Kent.

When they got to Rochester they found a Traveller encampment on top of the stone but managed to talk them into helping carry it to the car.

Finally, they got back to Scotland and the stone was handed over to other members of the the Scottish Covenant Association, who were campaigning for a Scottish Parliament.

The Stone of Destiny in the custody of James Wiseheart in April 1951

Hamilton was glad to get rid of it as suspicion was already falling on him.

Detectives discovered that Hamilton had taken out nearly every book in Glasgow's Mitchell Library on the subject of the Stone of Destiny in the months before the theft.

By now the main part of the stone was hidden under the floorboards at a factory in Bonnybridge.

It was later removed to a more remote location near Cambuskenneth Abbey in Stirling.

The second section was brought up from Birmingham and was eventually put back together with the larger piece by a stone mason using copper tube doweling.

The stone was taken back to London after it was found at Arbroath Abbey

After a few months, the Scottish Covenant Association decided the stone should be returned. The heist had served its purpose of publicising the cause of Scottish home rule.

They decided to leave the stone at the ruined abbey of Arbroath, where a famous statement of Scottish independence was made in 1320.

On 11 April 1951, the stone was taken back to London and returned to Westminster Abbey.

The stone was replaced in the Coronation Chair and two years later, in June 1953, King Edward's chair - with the Stone of Destiny underneath - had a greater prominence than ever as Queen Elizabeth's coronation was broadcast on television.

Forty years later, in July 1996, the Queen, along with Prime Minister John Major, agreed the stone should be returned to Scotland. It can now be seen at Edinburgh Castle.

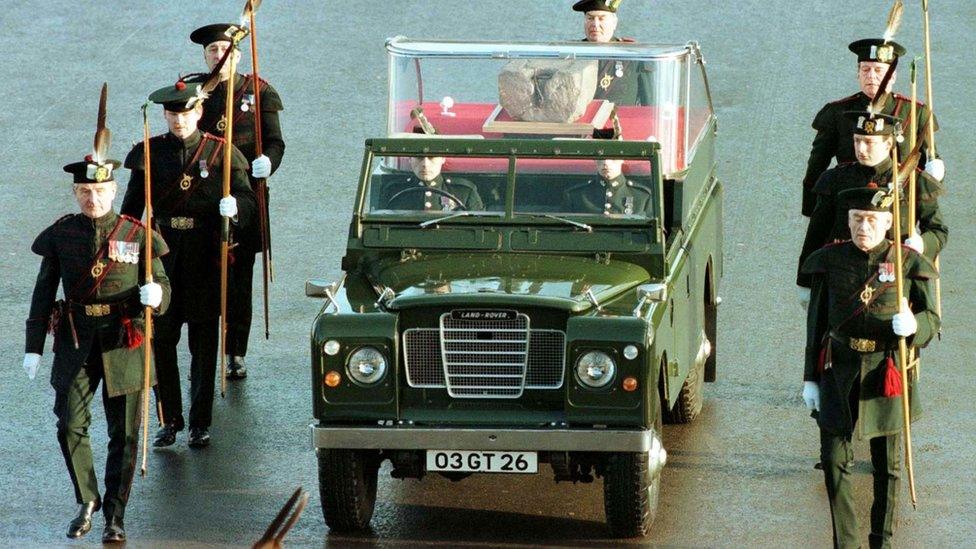

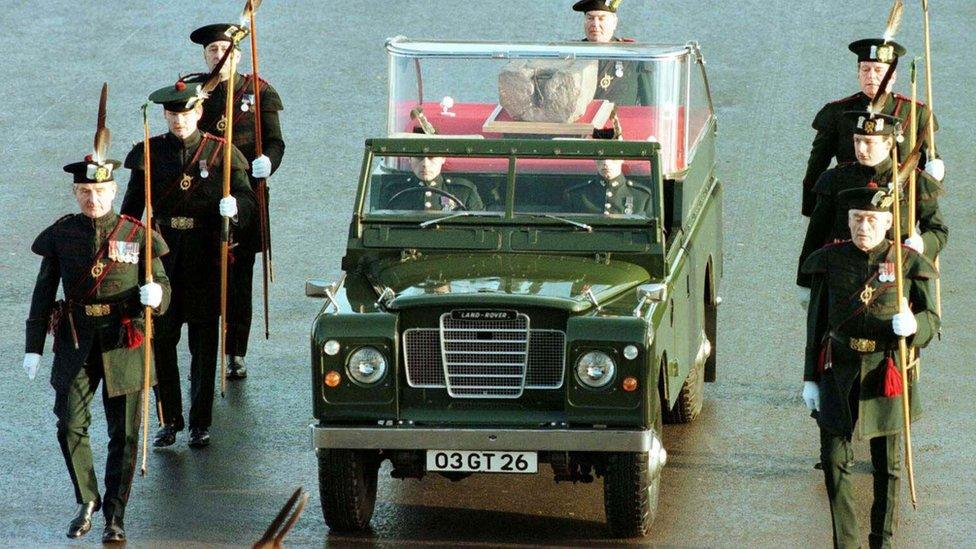

Members of the Royal Archers escort the Stone Of Destiny across Edinburgh Castle Esplanade in 1996

In the next couple of years the Stone of Destiny will move once more, to become the centrepiece of a planned Perth City Hall museum.

It has also been announced that it will return to Westminster Abbey for the coronation of King Charles III.

Ian Hamilton went on to have a successful career in criminal law.

Kay Matheson returned to Inverasdale in the west Highlands. She was a teacher in the local primary school, and died in 2013.

Gavin Vernon graduated in electrical engineering and emigrated to Canada in the 1960s. He died in March 2004.

Alan Stuart had a successful business career in Glasgow and died, aged 88, in 2019.

Kay Matheson welcomed the stone back to Scotland during a ceremony at Edinburgh Castle in 1996

The student gang were never prosecuted for their actions.

No-one had been harmed, the government said, even if the stone had a bumpy ride.

Ian Hamilton added: "The home secretary made a statement to the House of Commons: 'It was known who had done it but it would not be in the public interest to prosecute the vulgar vandals'.

"That's been a phrase that I have always enjoyed all my life.

"To do something for your country that spills not a drop of blood is, I think, something to be proud of."

Related topics

- Published17 March 2023

- Published4 October 2022

- Published27 November 2021

- Published6 April 2020