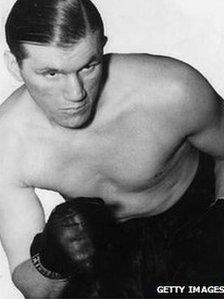

Tommy Farr: Boxer who fought his way out of pits

- Published

Tommy Farr fought an epic battle with champion Joe Louis in 1937

The question of who was the greatest pound-for-pound boxer ever to have come out of Wales has been endlessly debated.

Yet despite having never won a world championship belt, Rhondda heavyweight Tommy Farr - who would have celebrated his 100th birthday on March 12 - was certainly close to if not top of the list.

Thomas Farr was born on 12 March, 1913 at his family home in Clydach Vale.

One of eight children, Farr grew up in abject poverty, even by the austere standards of Edwardian industrial Wales.

His mother Sally died of bronchitis by the time he was nine, and shortly afterwards his father, Irish bare knuckle fighter George, was gravely injured in a mining accident at the Cambrian Colliery. Farr became the main breadwinner and began working down the pits which had injured his father.

Welsh boxing historian and referee Winford Jones says it was his loathing of the mines rather than any love of boxing which first drove a 12-year-old Farr into the ring.

"Tommy didn't want to be a boxer, he wanted to be a chef. But even at 12 Tommy was a lump of a lad, and so started making a few bob by fighting grown men at the boxing booths at the fair," he said.

"They weren't sanctioned fights against opponents matched in weight. If they thought they could win the prize on offer, anyone in the crowd - young or old, big or small - could pay sixpence and have a pop at Tommy.

"Yet Tommy himself described it as the lesser of two evils when compared to coal mining, and he made his employers an awful lot of money."

Tommy Farr rose from obscurity in the south Wales valleys

At the age of 18, Farr moved to London to make his name. His outstanding bravery in the ring drew the attention of boxing writers, although his early record was stubbornly mediocre.

According to Mr Jones, this made Farr a hard man to love in those early days.

"You could say Tommy had a chip on his shoulder. He certainly resented all the attention [fellow Welsh boxer] Jack Petersen was getting," he said.

"Tommy thought he could beat Petersen and that he was running scared from fighting him. Tommy became convinced the press were biased because Petersen came from Cardiff."

Mr Jones argues that much of Farr's perceived prickliness was people misinterpreting his dry humour.

"At the weigh-in for his fight against [American boxer] Joe Louis, Louis asked Tommy how he got the blue coal scars on his back."

"Rather than telling him they were from crawling in tiny holes down the mines, Tommy said they were from fighting tigers in his days on the circus," he said.

Farr's career turned the corner in 1935, when he teamed-up with trainer Ted Broadribb.

The 'Brown Bomber'

Farr came to be talked of as a world title challenger as he followed up winning the British and Empire heavyweight title from Ben Foord, with victories over Germans Walter Neusel and former world champion Max Baer.

The scalps of Neusel and Foord in particular greatly boosted his confidence, as both opponents had previously seen off Farr's illusive adversary, Jack Petersen.

The fight the world wanted to see was Farr against The Brown Bomber, Joe Louis.

However there had been doubts the fight would happen after Farr came under pressure from the British Boxing Board of Control to instead fight German boxer, Max Schmeling.

But Farr relinquished his British and Empire belt in order to travel to New York to fight Louis at Yankee Stadium in August 1937.

Despite losing the bout, Prof Peter Stead, co-author of Wales and Its Boxers, said that night Farr finally won a much more valuable prize - the love of his nation.

"You could argue that Tommy's fight against Louis was the first sporting media event on a Wales-wide basis.

"Tonypandy town hall was opened in the middle of the night so the community could listen to it together, but so many turned up that they had to rig extra speakers outside.

"At Tommy's old colliery they tried to rearrange the shifts so as many of the miners as possible could listen, and for those unfortunate enough to have to work underground while it was on, updates on the progress were chalked on the sides of the coal drams sent down in the cages.

'Dug up road'

"The power of radio brought Wales together behind Tommy that night, and his courageous performance kept us there. I think that love meant more to Tommy than all the belts he won."

He became only the second man to take Louis to the 15-round distance, but lost a narrow points decision.

Harry Carpenter and Mike Tyson discussed the Farr-Louis fight in 1987 for BBC TV

Whilst the verdict outraged his fans back home, Farr admitted the better man won on the night.

"My face looked like a dug-up road after he'd finished with it. I've only got to think about Joe Louis and my nose starts bleeding," he said at the time.

Despite losing three more clashes against top American opposition, Farr went the distance with all of them.

He retired a wealthy man in 1940, but 10 years later poor investments had cost him his fortune, forcing him to make a comeback.

"Tommy had no need to fight again, his heart wasn't in it, and his place in boxing folk law had long been guaranteed," said former BBC Wales boxing commentator John Evans.

"But as so often happens to boxers, he was lured back into the ring for financial reasons."

Farr reclaimed the Welsh heavyweight title in 1951, finally retiring at the age of 39 after a seventh-round loss to Don Cockell in a 1953 final eliminator.

"If there's anything to take out of that comeback, it's Tommy's impeccable sense of occasion because after he lost to Don Cockell, he took the microphone from the MC and brought the curtain down on his career by leading the crowd in a rendition of Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau… pure Tommy Farr."

Farr lived out his life after his second retirement running a pub near Brighton.

He died on 1 March 1986, just shy of his 73rd birthday, and his ashes were buried in the same plot as his parents in Trealaw Cemetery.

- Published12 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013