Cardiff University: X-rays 'read' ink in historic scrolls

- Published

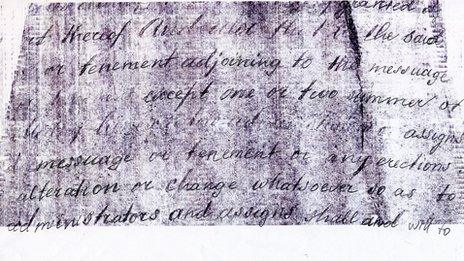

The technique works by scanning parchment with X-rays to reveal the text within

X-ray technology which scans the iron used in ancient ink has been developed by scientists at Cardiff University to help them read historical documents.

The breakthrough allows scholars to see virtually the contents of parchments which are too fragile to unroll.

A 3D image of the iron is built up from a series of X-ray "slices," creating "genuinely legible" high contrast text, say experts who developed the software.

Prof Tim Wess said it was a "milestone in historical information recovery".

The team at Cardiff University and Queen Mary, University of London, built their own scanner for the project because no commercially available machines were suitable.

Funded with a £1.3m grant from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the scanning is carried out in London.

Scrolls do not need to be unrolled when put on the scanner for the X-ray 'slices'

The software to interpret the findings was developed in Cardiff.

The team claims the development will allow fragile rolled-up historical documents to be read for the first time in centuries.

Prof Wess said: "The conservation community is rightly very protective of old documents and isn't prepared to risk damaging them by opening them.

"Our breakthrough means they won't have to.

"Across the world, literally thousands of previously unusable documents up to around a 1,000-year-old could now become available for historical research.

"It really will be possible to read the unreadable."

The technique detects the presence of iron contained in "iron gall ink" which was typically produced by adding a source of iron, such as nails, to gallotannic acid.

The scrolls are 'read' using computer-generated 3D imagery

Iron gall ink was the ink most commonly used from the 12th to 19th Centuries.

'Features in teeth'

The computer-generated 3D image is created using a technique called microtomography which pinpoints the location of the iron.

It allows the image to be unrolled virtually, revealing the contents.

Medieval legal scrolls from Norfolk Record Office were the first to be put to the test.

The scanning took place at the Institute of Dentistry at Queen Mary.

Dr Graham Davis, who led the team, said the scanners were being adapted for other scientific uses, including dentistry.

He said: "Enhanced high contrast images are enabling the detection and analysis of features in teeth that we haven't been able to see before."