How Land Girls helped feed Britain to victory in WW1

- Published

The Women's Land Army played a vital role in World War One

Three million British men fought in World War One, but just as important to the war effort were the women they left behind.

By 1915 Germany's best chance of victory lay in starving Britain into surrender through a naval blockade, so the country had to become more self-sufficient in food.

At the start of the war Britain produced just 35% of the food it ate.

So the work of the Women's Land Army was vital in the Allies' victory.

While the formation of the Women's Institutes in Wales helped conserve food, it was the Women's Land Army (WLA), or Land Girls, who took on the task of producing it in the first place.

Britain's food imports made up around 50% of the country's requirements, so when Germany successfully mounted naval blockades in 1915, the country faced a problem.

Then, in 1917, the harvest failed and Britain was left with just three weeks' of food reserves. Famine loomed.

The Board of Agriculture set up the Women's Land Army and over a quarter of a million volunteers flocked to help.

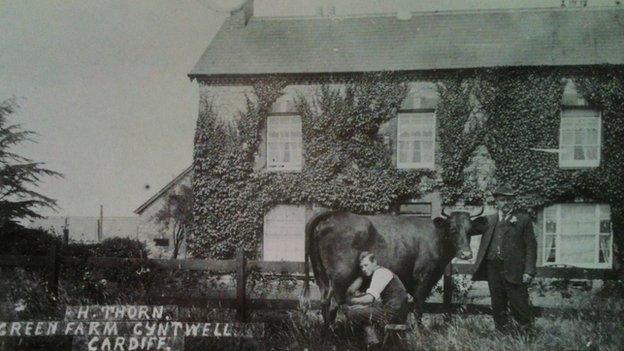

Agnes Greatorex from Cardiff left a life in domestic service for the very different world of Green Farm in Ely, Cardiff, now a hostel for homeless people.

As part of the BBC's All Our Lives series in 1994 she went back to re-live the day she swapped the front parlour for the milking parlour.

She said: "We had to get up at five in the morning for milking, and then we'd have to take it up to Glan Ely hospital. After that - especially during the winter - we'd have to muck-out the cow sheds. Then we might get half an hour for breakfast.

Farms like Green Farm in Ely were vital to Britain winning the war on the home front

"I'd be out there picking up stones from the field or cutting hay, and I'd be as happy as a lark."

She believed that, although her work on Green Farm was equally as arduous as that in service, being a Land Girl gave her a glimpse into the future.

"When I became a Land Girl I thought that's it, I'm independent," she said.

"I had a pound a week, not as much as the men but a lot still - there was no-one to boss me, no more running around at the beck and call of the cook.

"I think the First World War did change women. Because once they'd had a taste they wouldn't go back to service, they were free."

Indeed it was not just the Land Girls' lives that would never be the same again - women not only had to help feed the nation, but also plug the gaping hole in labour left by the millions of men off fighting.

For the first time a door had been opened on previously male-only professions such as the railways, engineering, police and fire brigade.

And as much as women helped shape the outcome of the war, the war also helped shape the outcome for women.

Swansea University's WW1 historian Dr Gerry Oram says that after the Armistice, the government had little choice but to acknowledge this new reality.

"There was little point in pretending anymore - women had proved they could take on any role a man had done, and they'd played an enormous part in winning the war," he said.

"The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 made it illegal to exclude women from jobs because of their gender.

Two college girls sawing a log as part of their agricultural work in May 1918

"This followed the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which enfranchised 8.5 million women, giving them a voice in Britain's government for the first time."

But male attitudes were slow to catch up with this new reality, a point demonstrated by the fact that the voting age was set at 30 for women, as opposed to 21 for men.

And whilst the inter-war years did indeed bring new found prosperity and freedoms for some women, for many more the hard-fought recognition proved little more than lip service.

Dr Oram believes that nowhere did old habits die harder than in Wales.

He said: "In theory women had legal protection, but the reality of the situation was that the economy was so depressed following the war that there simply wasn't the jobs for them to go into.

Women worked on the railways to help keep Britain moving

"Add to that the amount of seriously wounded men coming home who required constant care, and in many instances women's lots were actually considerably worse after 1918.

"The Sex Discrimination Act was at odds with other legislation which promised servicemen their pre-war jobs back when they returned, and given the post-war collapse of heavy industry in Wales, there were even fewer jobs to go around here than elsewhere.

"In fact in Wales women had comprised 27% of the labour force in 1911, but that actually fell to 21% by 1931."

But even if post-war economic hardship delayed many of the social changes Welsh women had hoped for, according to Dr Oram there was nevertheless a lasting effect.

"Yes, there were fewer women working in Wales, and many of those who were working had been forced to go back to the domestic service they'd been trying to escape," he said.

"But after WW1 they travel further afield for employment, to London etc, and their horizons begin to broaden. This is when you start to see many of the Welsh societies springing up outside of Wales.

"Economic activity is just one way of measuring social change; after the war women travel more, are better educated, and start to have a greater voice in politics and the arts.

"Even if there wasn't an immediately noticeable benefit, there was however a shift in attitude, a sense that things could be different, which fed into social change later in the 20th Century."

- Published1 January 2013